Roman emperors had so few children due to a combination of social customs, political concerns, biological factors, and economic realities that shaped family life and reproduction in ancient Rome. They followed strict monogamous marriage rules and were often cautious about public image. Fertility issues, contraception use, and costly childrearing also played roles in limiting imperial offspring. Political rivalries and legal norms further influenced their family size.

Roman society emphasized monogamy for elite men, unlike some other ancient cultures. Roman men could have only one legal wife at a time. Divorce was common but required valid reasons like infertility or abuse. Polygamy was not accepted, and though some men took mistresses, it was socially frowned upon among the upper classes. This structure restricted the number of legitimate children an emperor could father simultaneously.

Political image mattered deeply. Julius Caesar divorced his wife Pompeia after a scandal to maintain a virtuous public image, showing how sensitive emperors were to reputational damage. Caesar’s unwillingness to associate with suspicion illustrates why emperors controlled their family narratives carefully. Moreover, emperors often removed rivals by eliminating illegitimate children. Caesar’s son with Cleopatra, Caesarion, was killed by Octavian to prevent dynastic competition. Such actions reduced the acknowledged number of children an emperor might have.

Sexual practices also influenced fertility. While Romans accepted same-sex relationships for men in dominant roles, rumors about Julius Caesar’s intimate passive relations with King Nicomedes of Bithynia suggest that sexual behavior might have impacted his reproductive output. Some historians speculate this contributed to fewer children born to him.

Roman warfare practices included the rape of conquered women, which was considered part of military victory. Such children were unrecognized in Roman family lines and thus did not augment emperors’ legitimate offspring. Additionally, emperors would not acknowledge such children, further reducing public family size.

Biological factors also mattered. Frequent use of hot baths, popular among Romans of all classes, may have impaired male fertility since constant exposure to high temperatures reduces sperm count. This likely contributed to fewer children born in aristocratic families, including emperors’.

Contraceptive methods existed and were used. The legendary plant silphium, extinct before the imperial era, was famed for preventing pregnancy. In later periods, herbs like pennyroyal acted as contraceptives or abortifacients. These means gave elite couples control over family size, making large numbers of children uncommon.

In response to low birth rates, Augustus passed laws encouraging marriage and childbearing. The Lex Iulia de Maritandis Ordinibus (18 BCE) required marriage. The Lex Papua Poppaea (9 CE) punished adultery and celibacy, compelling widows and divorced women under fifty to remarry. Despite laws promoting progeny, birth rates among elites stayed low.

The high economic cost of raising well-educated children was also a factor. Raising children in senatorial families was comparably expensive to modern Europe. Aristocrats hired Greek tutors and invested in extended education, weighing heavily on finances. Some prominent Romans gave children up for adoption due to these expenses.

Low fertility trends affected mainly urban elites. While many Romans desired children, infertility and social conditions reduced their number. Rural populations maintained the empire’s overall population levels, suggesting these challenges were concentrated within imperial and aristocratic circles.

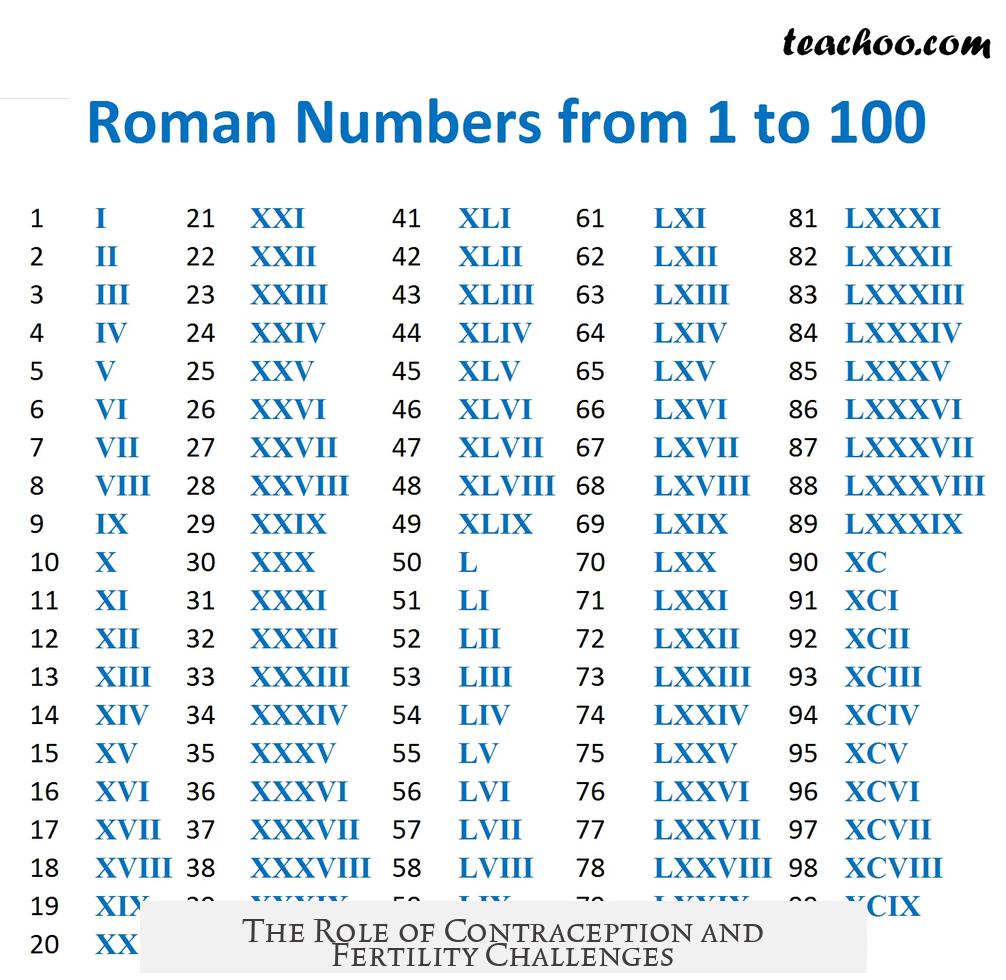

| Factors | Description |

|---|---|

| Monogamy and Divorce | Only one legal wife; divorce required cause; limited simultaneous offspring. |

| Political Image | Divorces and elimination of illegitimate heirs to protect public reputation and power. |

| Sexual Practices | Same-sex relations and unacknowledged children from war did not contribute to family size. |

| Biological Factors | Frequent hot baths possibly reducing male fertility. |

| Contraception | Use of abortifacient herbs allowed family size control. |

| Legal Pressures | Laws prescribed marriage and penalized celibacy, though results varied. |

| Economic Factors | High cost of raising elite children limited family size. |

- Roman emperors conformed to monogamous norms limiting simultaneous wives.

- Political concerns led to divorces and the removal of illegitimate heirs.

- Sexual behaviors and rumors may have decreased fertility for some emperors.

- Biological and environmental factors like hot baths affected reproductive capacity.

- Contraceptive herbs provided means to limit children.

- Economic burdens of childrearing among elites reduced family size.

- Imperial marriage laws sought to boost birth rates but met limited success.

Why Did Roman Emperors Have So Few Children?

Roman emperors had surprisingly few children due to a mix of cultural, political, personal, and economic factors intertwined in their lives. This isn’t just a random historical trivia—it reflects how Roman society, especially at the elite level, shaped family dynamics in ways that can seem counterintuitive today. Let’s dive into this intriguing puzzle and uncover why Caesars didn’t flood the empire with heirs.

Roman Marriage and Family Norms: The Monogamy Curveball

Contrary to the popular image of Roman debauchery rife with harem-style indulgence, Rome was a strictly monogamous culture when it came to marriage. Roman men had ONE wife at a time, no concubines officially allowed. Divorce? Sure, but only with solid reasons like infertility or abuse. So, the idea of emperors multiplying children through multiple wives simultaneously? Nope, legally off the table.

Even the biggest players among Roman elites played by these rules—though they could have *several* wives over a lifetime through divorce and remarriage, only one counted at a time. Mistresses existed but weren’t socially endorsed. Augustus, the first emperor himself, cracked down hard on adultery with the Lex Iulia, pushing traditional family values.

Political Image: The Emperor’s Carefully Curated Family Album

Take Julius Caesar, for example. His personal life was a chessboard of image control. He famously divorced his second wife Pompeia due to scandal, claiming “my wife ought not even to be under suspicion.” That’s political damage control in full swing.

Caesar had an illegitimate son, Caesarion, with Cleopatra—but never officially acknowledged him. Why? Recognizing a son born outside sanctioned Roman marriage would weaken Caesar’s political image and open succession crises. Indeed, Caesarion was eliminated by Octavian to prevent dual ‘Caesars’ confusing Rome. Political survival weighed heavier than fatherly pride.

Sexual Politics and the Impact on Offspring

Roman sexual norms influenced childbearing in ways less obvious to outsiders. On one hand, Roman legions considered rape a grimly accepted part of warfare against defeated peoples—not something that would lead to legitimate heirs.

On the other hand, same-sex relationships were common and socially tolerated if you kept the right role. Julius Caesar had persistent rumors about a passive homosexual relationship with King Nicomedes. Whether true or not, such rumors could cloud public acceptance of offspring or discourage prolific parenthood.

The Role of Contraception and Fertility Challenges

Ancient Romans had some knowledge of contraceptives. The famous plant silphium, now extinct by Caesar’s time, was prized for birth control. Later, herbs like pennyroyal served as abortifacients. These were certainly used by some in the elite circles.

Interestingly, Augustus enacted laws forcing citizens to marry and bear children to curb low birth rates. His Lex Iulius and Lex Papua Poppaea imposed penalties to encourage marriage and childbearing—implying a recognized fertility issue in the upper classes.

There’s even speculation that Roman bathing habits—frequently in scalding hot waters—may have harmed male fertility by affecting sperm quality. This suggests biological factors also played a role in limiting children.

Money Talks: Economic Costs of Raising Roman Children

Raising children wasn’t cheap, especially for the elite. Senator Lucius Aemilius, for instance, gave two of his sons up for adoption simply because he couldn’t afford to support them all. Education costs were steep. Wealthy Romans often hired expensive Greek slave tutors to raise their children properly.

Given these financial burdens, some elites may have opted for fewer children to ensure better resources and status for those they did raise.

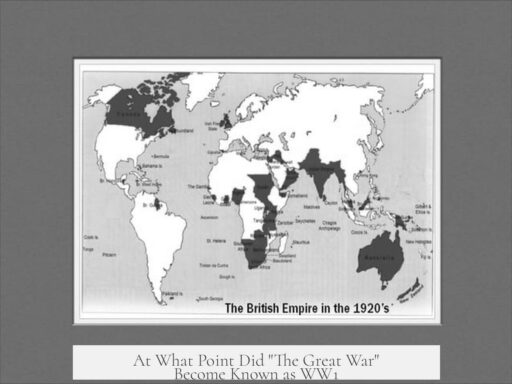

Urban vs. Rural: Fertility Differences in Society

Most of these points focus on the elite or urban Roman classes. Low birth rates were particularly noticeable in cities. But rural peasants might tell a different story. The empire’s overall population didn’t plunge significantly, suggesting countryside families maintained higher fertility despite city trends.

This disparity implies the pressures limiting elite Roman family size—like political image, legal controls, and cost—were less impactful in rural areas.

So Why Did Roman Emperors Have So Few Children? The Sum of All Parts

It’s a cocktail of culture, politics, economics, and biology:

- Monogamous marriage laws limited multiple-spouse fertility.

- Political image management meant divorces, discreet handling of illegitimate children, and limiting heirs to avoid succession chaos.

- Sexual norms and rumors possibly reduced progeny or their public acceptance.

- Use of contraceptives and abortifacients although limited, played roles alongside biological factors like bathing habits affecting fertility.

- High costs of raising and educating children incentivized smaller elite families.

Even with all this, many Romans wanted children but struggled with fertility, especially in urban areas. That probably explains why emperors, whose lives were under intense public scrutiny and often bound by political necessity, ended up with surprisingly few offspring.

What Can Modern Readers Learn From This?

It fascinates how ancient family strategies combined practical, personal, and political reasons. The Romans cared about legacy, but not just in the quantity of children produced. It was more about controlled succession, reputation, and resource management.

Next time you hear “Roman emperor,” don’t just picture parties and conquests. Think also of the careful balancing act behind the scenes—a world where even fatherhood had rules, pressures, and costs shaping history’s course.

Curious about other quirks of Roman family life? Or wondering how power and parenting mix in today’s leaders? Let’s keep the conversation going!