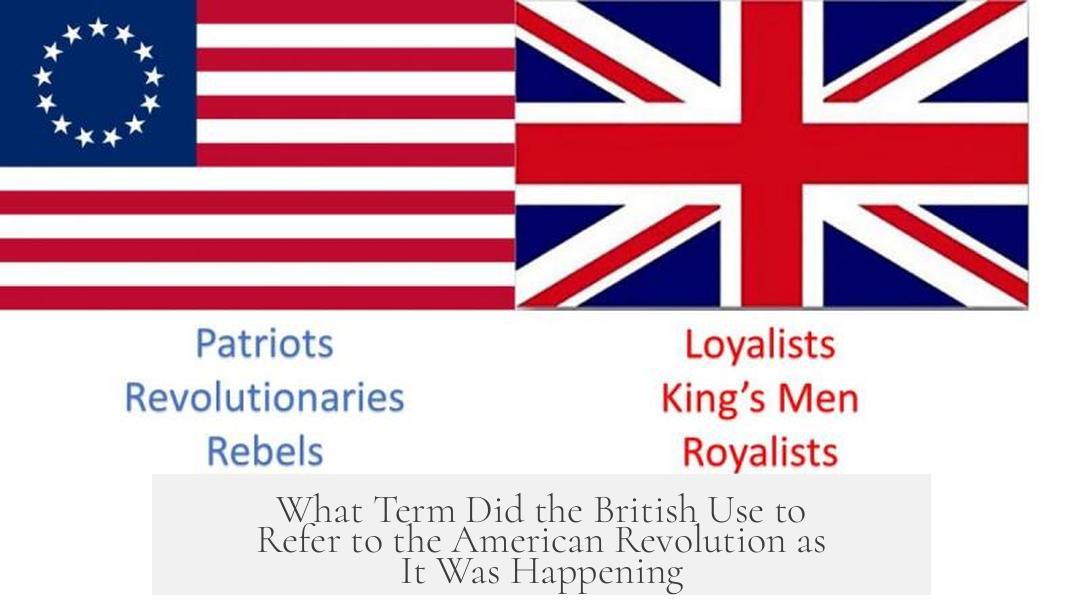

The British referred to the American Revolution primarily as a “Rebellion” or by similar terms emphasizing illegitimacy rather than as a legitimate revolution while it was happening. Key figures, including King George III, consistently used words like “rebellion,” “revolt,” and “insurrection” in official speeches and documents. These terms reflected their perspective that the conflict was an unlawful uprising rather than a popular or political revolution.

King George III’s addresses to Parliament illustrate this usage clearly. In an October 27, 1775 speech, he described the situation as “their [American’s] revolt, hostility and rebellion.” He framed the events as a “desperate conspiracy” and called the conflict “The rebellious war,” rejecting the idea of a legitimate revolution. Similarly, in November 1777, the King spoke of “the continuance of the Rebellion in North America,” reinforcing the term within official discourse.

British officials often described the conflict as a “usurpation” by a small, elite group that hijacked the existing British institutions rather than a genuine political revolution. This framing suggested a change in leadership rather than the establishment of new governance. For instance, a letter from Dumfries dated April 19, 1777, referred to efforts aimed at “suppressing the unnatural Rebellion of your deluded subjects in America.”

Beyond “rebellion,” other terms occasionally appeared, such as “insurrection,” “the Revolt of America,” or “the revolted colonies.” However, none of these phrases achieved universal use. The British preferred language that delegitimized the conflict, portraying it as disorderly and unlawful resistance rather than a rightful revolution.

| Term | Context | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Rebellion | Primary term in political speeches | “The present situation… their revolt, hostility and rebellion” – King George III, 1775 |

| Usurpation | Describes leadership change | “A usurpation rather than a revolution” – King George III’s view |

| Insurrection | Used in some official documents | Occasional references to “insurrection” in correspondence |

| Revolt of America | Alternative descriptor | Appears sporadically in semi-official discourse |

- The British chose terms focusing on illegitimacy and disorder, avoiding “revolution.”

- King George III prominently framed the conflict as rebellion and usurpation.

- No single universal phrase existed, but “rebellion” dominated political language.

What Term Did the British Use to Refer to the American Revolution as It Was Happening?

The British primarily referred to the American Revolution as a “Rebellion” or variations of that term during the conflict. This choice of words wasn’t just a slip of the tongue. It was a deliberate way to frame the conflict as illegitimate and unlawful—more a messy uprising than a noble fight for independence.

“Rebellion” dominated British official language, especially in speeches by King George III and parliamentary discourse. But the British vocabulary on this mattered deeply. Terms like “revolt,” “insurrection,” and “the rebellious war” pepper historical records, showing a consistent effort to deny the American cause the status of a true revolution.

The King’s Take: Rebellion Over Revolution

King George III, who had the final say in many official communications, used “rebellion” often. On October 27, 1775, in a speech to Parliament, he described the crisis as:

“their [American’s] revolt, hostility and rebellion.”

He dismissed it as “a desperate conspiracy rather than a revolution,” calling the ongoing conflict “The rebellious war.”

This choice of words signals the British mindset. They regarded the American leaders not as freedom fighters but as lawbreakers undermining their rightful authority. The word “usurpation” also appears to describe American leadership, framing the conflict as a power grab rather than a political revolution.

It’s an interesting way to look at history: instead of acknowledging a movement toward new governance, British officials saw a power struggle veiled as politics. To them, it wasn’t about democracy but about a few elites hijacking institutions put in place by Britain.

“Rebellion” Was the Dominant Label, But Not the Only One

While “rebellion” was king, it wasn’t the sole term in use. Official documents, letters, and newspapers also referenced the conflict as:

- Insurrection

- The Revolt of America

- The revolted colonies

This variety shows that although there wasn’t one fixed phrase, the underlying theme remained consistent—casting the American cause as illegitimate upheaval rather than a rightful revolution.

For example, a letter from Dumfries dated April 19, 1777, refers to the Americans as “deluded subjects” engaged in an “unnatural Rebellion.” The term “unnatural” carries deep judgment here, not just legally but morally.

Why Did the British Reject the Term “Revolution”?

The British resisted calling it a “revolution” because that word suggests legitimacy, perhaps even approval of a political change. To admit the American struggle was a revolution would undercut their claim to authority and the idea of loyalty to the Crown.

“Rebellion” and its synonyms imply disorder, illegality, and chaos—which suited British interests. It painted the Americans as traitors stirring trouble, rather than people pursuing rightful self-determination.

The British approach also made the conflict clearer for loyalists: the Crown demanded order, and those who opposed it were rebels, period.

Tracing Usage Through Official Records

The London Gazette, a key official publication of the time, repeatedly referred to the conflict with variation of the term “rebellion.” For instance:

- Issue 11762, April 19, 1777: Language condemning the rebellion and calling for its suppression.

- Issue 11824, November 20, 1777: Mentions “the continuance of the Rebellion in North America.”

Public readings of speeches and newspapers echoed similarly harsh terms emphasizing lawlessness rather than revolution.

The British Narrative’s Real-World Impact

Choosing “rebellion” over “revolution” shaped how Britain conducted the war and engaged with colonists. This choice justified harsh military responses and attempts to “suppress” rather than negotiate with insurgents.

The ripple effect? It hardened British resolve to crush the uprising, while American leaders pressed harder for independence, knowing their struggle was framed as criminal activity by their rivals.

What’s the Takeaway for Today’s Readers?

Knowing the British terms enriches understanding of how language influences history. It prompts us to ask:

- How does labeling a conflict change its perception and outcome?

- What happens when one side denies the legitimacy of change sought by another?

- Can calling something a “revolution” or “rebellion” change the moral or political lens forever?

Today, when historians say “American Revolution,” that term carries recognition of legitimacy. But at the time, the British clearly wanted none of that. To them, it was a treacherous rebellion threatening the empire’s authority.

In conclusion, while there was no one fixed phrase the British used, the words “rebellion,” “revolt,” and “insurrection” were predominant. These terms underscored their view of the conflict as an unlawful disturbance, not a legitimate revolution. This linguistic framing played a key role in shaping attitudes and actions on both sides.

Isn’t it fascinating how the power of words can shape the course of history? Next time you hear “revolution” or “rebellion,” remember these aren’t just synonyms—they are windows into how people saw the world and fought for its future.

Sources

- King George III Speech, October 27, 1775 – Library of Congress

- London Gazette Issues 11762 & 11824 (1777)

What term did King George III primarily use to describe the American Revolution?

King George III mainly called it a “Rebellion” in his official speeches. He described it as a “desperate conspiracy” and “The rebellious war,” focusing on its illegitimacy rather than recognizing it as a revolution.

Did the British ever call it a “revolution” during the conflict?

No, British leaders generally avoided the term “revolution.” They treated it as a usurpation or leadership change caused by a small elite, not a popular political revolution.

Besides “rebellion,” what other terms did the British use for the conflict?

The British also used terms like “insurrection,” “revolt,” “the Revolt of America,” and “revolted colonies.” However, no single phrase was universally applied.

Why did the British prefer the term “rebellion” over “revolution”?

They aimed to emphasize that the conflict was an illegal uprising against rightful authority. Using “rebellion” suggested disorder and illegitimacy instead of a legitimate push for independence.

Was there an official British phrase that described the American Revolution?

There was no single fixed phrase. Official documents mostly used variations of “rebellion” or “the Rebellion in America,” reflecting their view of the conflict as an act of insubordination rather than a formal revolution.