The Dutch East India Company, known as the VOC, was once a dominant force in global trade. It ultimately dissolved around 1800 due to internal corruption, colonial unrest, increasing competition from rivals, and failure to adapt to changing global markets. Political events during the Napoleonic Wars finalized its end, with its assets transferred to successor governments.

The VOC began in 1602 with a monopoly on Dutch trade east of the Cape of Good Hope. Supported by the Dutch state, it rapidly grew into a powerful, quasi-governmental entity. It ran its own military, administered colonies, and controlled vast trade networks. Headquarters in Batavia (modern Jakarta) served as the operational center. For much of the 17th century, it rewarded investors with steady dividends.

Despite its initial success, several factors eroded the VOC’s dominance. Corruption became widespread within overseas company offices. Officials often prioritized personal gain over company interests. In the Cape Colony, settlers clashed with VOC authorities who controlled prices and limited their freedom. Attempts to silence complaints from colonists only deepened unrest. By the late 1700s, many settlers asserted independence from VOC control.

- Corruption increased markedly in Batavia, fueled by the larger wealth at stake there.

- Colonial tensions undermined company authority and operational effectiveness.

- These internal problems drained resources and morale.

Meanwhile, economic pressures mounted. The VOC faced stronger rivals in European trade. Profit margins shrank as competition intensified and overhead increased. Its original focus on spices became outdated by the 18th century. Global trade shifted toward tea from China and India, markets the VOC struggled to dominate.

The VOC’s tea trade faced several challenges:

- The company refused to adopt the Chinese preference for silver transactions, sticking to barter-based spice trades instead.

- Its tea was poorer in quality compared to British offerings, hurting demand.

- Rising global tea supplies and falling prices left the VOC unprofitable.

By contrast, the British East India Company capitalized on tea’s rising popularity. It exploited plantations in India and adapted trade methods that appealed more to Chinese merchants. Thus, the British overtook the VOC as Europe’s main tea supplier during the 18th century.

The political landscape hastened the VOC’s collapse. The Napoleonic Wars disrupted European power dynamics. When the French conquered the Netherlands, the VOC—already financially strained—was liquidated around 1800. Its territories and assets passed to the Batavian Republic, a French puppet state. Later, with the Dutch monarchy restored, many holdings transferred to Dutch government control. Some regions, like the Cape Colony, were ceded to Britain as part of war settlements.

| Factor | Description | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Corruption | Widespread abuses and personal enrichment within VOC overseas offices. | Weakened governance, eroded trust. |

| Colonial unrest | Disputes and resistance from colony settlers, particularly in Cape Colony. | Reduced control, increased operational problems. |

| Economic competition | Rise of competitors, notably British East India Company in tea trade. | Declining profits, market loss. |

| Failure to adapt | Sticking to outdated spice trade methods, poor tea quality. | Lost customer base, diminishing relevance. |

| Political upheaval | Napoleonic Wars and French conquest of the Netherlands. | Collapse, liquidation, transfer of assets. |

In summary, the VOC’s fall stemmed from a mix of internal failings and external pressures. Corruption and colonial defiance undermined its authority. The shift in global trade patterns outpaced its business model. Competitors seized market advantages with superior products and flexible practices. The Napoleonic Wars delivered the final blow, ending one of the world’s earliest multinational corporations.

- The VOC began in 1602 as a Dutch state-backed monopolist in Asian trade.

- It wielded military power, governed colonies, and generated profits peak in the 17th century.

- Corruption and colonial unrest weakened its operations over time.

- Failure to adapt to tea trade and competition from British East India Company reduced profits.

- The Napoleonic Wars and French conquest led to its liquidation by 1800.

- Its assets transferred to Dutch government and other colonial powers.

The Dutch East India Company: The Rise, Fall, and What Really Happened to It

Few entities in history have held sway quite like the Dutch East India Company, or VOC, did in its heyday. Founded in 1602, it was much more than a mere trading company. It crowned itself a maritime empire with militarized power, quasi-governmental authority, and a far-reaching monopoly linking Europe to the rich spice islands and beyond.

But what exactly happened to this titan of trade? The answer isn’t just about bankruptcy or competition. It’s a tangled tale involving corruption, stubborn trading practices, political upheavals, and a failure to adjust as the world changed. Let’s unravel this together, piece by piece.

Setting the Stage: Origins and Influence of the VOC

The VOC, or Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie, sprang to life in 1602 with Dutch government backing. It was granted a state-sanctioned monopoly over trade eastward from the Cape of Good Hope. In plain speak: only the VOC could legally trade in this vast region under Dutch rule.

Divided into 17 directors—the Heeren XVII—this company was unique, straddling roles of merchant, ruler, and military power. Unlike present-day corporations confined by law, the VOC operated overseas like an autonomous state, conquering land, managing production, and waging wars where needed.

Batavia (modern Jakarta) on Java island became their operational capital, ensuring smooth control over massive trade volumes. For almost two centuries, investors enjoyed hefty dividends. Profits from spices, silks, and other exotic goods seemed unstoppable.

Cracks Begin: Corruption and Colonial Unrest

All empires, no matter how mighty, have their Achilles’ heel. In the VOC’s case, it was corruption—especially rampant in far-flung overseas offices. The sheer wealth flowing through these regions tempted colonial governors and officials to skim off the top. This wasn’t a sneaky side hustle; it systematically undermined the company’s efficiency.

Take the Cape Colony, a crucial resupply base founded in 1652. Colonists here had a stormy relationship with the VOC’s grip on commerce. The company tried to control prices and restrict travel to prevent dissent, especially after colonists voiced legitimate grievances that the directors back home never addressed.

By the late 1700s, the “trekboers”—farmers pushing inland—started asserting their independence, frustrated by the VOC’s neglect and heavy-handed control. Farther afield, in Batavia, the corrupt atmosphere thrived even more because enormous wealth exaggerated temptations.

Economic Challenges: Stiff Competition and Shifting Markets

Although corruption was a big part of the problem, external factors sealed the VOC’s fate. By the 18th century, the company’s 17th-century trading model looked archaic. It was built to monopolize spices, not to dominate the rising tea trade that was booming in Asia and Europe.

The tea trade was a game-changer, and the VOC was late to join. Their tea quality was notorious for being inferior. Plus, their refusal to adopt flexible, silver-based trade methods, preferred by Chinese merchants, alienated key partners. While British competitors adapted quickly and exploited Indian tea cultivation after Chinese ports closed, the VOC clung to outdated approaches.

This rigid stance quickly turned from stubbornness into self-sabotage. The British East India Company (EIC) surged ahead, becoming Europe’s premier tea supplier. Dutch traders, stuck with lower-quality tea and hostile trading terms, lost ground rapidly.

Maintaining control over conquered territories drained money and manpower. The company wasn’t just trading anymore—it was managing colonial governance, dealing with indigenous conflicts, and frustratingly, fighting expensive wars. All this overhead squeezed profits tight.

The Final Blow: Political Upheavals and Liquidation

By the late 1700s, the VOC was teetering on bankruptcy’s edge. Corruption, changing markets, cost overruns, and rising competitors gnawed at its core. Then came the Napoleonic Wars, shaking Europe’s political landscape.

Napoleon’s conquest of the Netherlands ushered in the puppet Batavian Republic. Within this political upheaval, the VOC quietly ceased operations around 1800. Its vast holdings either moved into Dutch government hands or, in cases like the Cape Colony, were handed over to the British as debt repayment.

The empire built in the name of the Dutch crown faded. But its legacy lived on in the colonial structures and global trade networks it influenced for centuries.

Lessons from the VOC’s Demise

Why does the VOC’s story matter today? Beyond the dramatic rise and fall, the company teaches key lessons:

- Adapt or perish: The VOC’s refusal to embrace new trade forms—notably in Chinese markets and tea quality—sealed its decline.

- Corruption is corrosive: No empire or corporation can thrive if its leadership is riddled with self-interest and greed.

- Balancing governance and commerce is tricky: Acting as a state and a company stretched resources thin and created administrative chaos.

- External forces can reshape fortunes overnight: Political turmoil, such as the Napoleonic Wars, can end even the mightiest ventures.

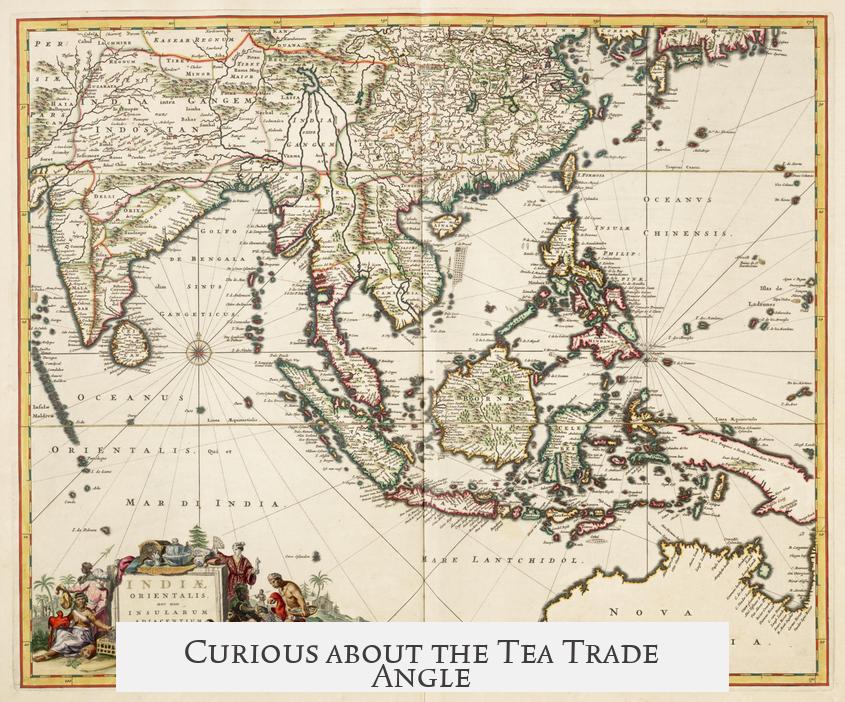

Curious about the Tea Trade Angle?

The tea trade, often underestimated, was crucial in changing VOC fortunes. While they focused on spices, the global infusion of tea reshaped consumer preferences—and money flow. British East India Company’s exploitation of Indian tea cultivation after Chinese ports closed created a deep market advantage.

VOC’s stubbornness not to adopt silver payments in Chinese trade—preferred over barter or goods—cut off buyers. Even worse, a flood of cheap, high-quality tea elsewhere hurt VOC’s ability to compete on price and quality. The once-dominant spice traders suddenly found themselves trailing in a vastly different game.

Recommendations for Further Reading

If you want to dive deeper into this fascinating topic, check out:

- The Dutch Seaborne Empire by Boxer (1965) – a classic on VOC’s maritime dominance

- Jan Compagnie in War and Peace by Boxer (1979) – explores the company’s military and political maneuvers

- Merchant Kings by Stephen Bown (2012) – covers global companies ruling the early modern world

- The Dutch Republic by Jonathan Israel – offers rich political context

- Dutch Ships in Tropical Waters by Parthesius (2014) – dive into VOC’s naval and commercial operations

In Closing: The VOC’s End was Inevitable but Impactful

The Dutch East India Company’s collapse was no sudden disaster—it was a slow unraveling caused by corruption, stubborn traditions, emerging rivals, and political storms. It faded quietly after nearly 200 years of dominance, but it changed the course of global trade forever.

So, next time you sip tea or ponder global trade empires, remember the VOC: a company that ruled with an iron fist but couldn’t bend with the winds of change.