China’s claim of 5000 years of history is a complex narrative shaped by varying perspectives, scholarly debates, and political motives. This extensive timeline, often presented as a continuous national legacy, is far from a settled fact and should be viewed as a constructed historical identity with contested foundations.

Several factors explain why the notion of “5000 years of Chinese history” is partly a national myth. The idea blends fragments of true historical events, mythic stories, and selective interpretations. China’s history, as understood today, does not represent a seamless or universally accepted account dating back five millennia. Instead, it fluctuates based on scholarly interpretation, archaeological discoveries, political influence, and cultural shifts.

Historians approach the 5000-year narrative differently. For example, scholars focused on the Qing dynasty (1636–1912) note that this epic dynasty only occupies a brief segment within the supposed 5000 years. Furthermore, the status of the Qing as part of “Chinese” history remains controversial, revealing how imperial succession narratives can be manipulated or reinterpreted.

During the 20th century, China’s origins underwent evolving interpretations. Initially, the 5000-year figure was not universally accepted. The historical timeline shifted notably as intellectual and political movements reimagined China’s beginnings. The belief in the antiquity of Chinese civilisation relates largely to traditional accounts beginning with the Xia and Shang dynasties, documented in Zhou dynasty chronicles.

- The Neo-Confucian school supported the broad truth of ancient texts, affirming Xia and Shang as historical realities.

- The Doubting Antiquity school (1910s) challenged this view, arguing many early records were politically motivated fabrications.

- More recently, the Believing Antiquity school has regained ground, endorsing archaeological findings that partially validate early chronicles—but critics caution this approach often slips into uncritical nationalism.

In addition, the Sino-Babylonian theory once proposed a Mesopotamian origin for Chinese civilization. Though largely discredited by archaeological evidence, this idea demonstrated how external narratives influenced Chinese historical identity in the early 20th century.

The 20th century also saw political movements attempt to redefine or erase aspects of China’s ancient past. The Cultural Revolution stands out, aiming to cut links with traditional history by destroying cultural relics. In practice, this effort failed. Still, its radical stance might have triggered the subsequent insistence on a glorified 5000-year history, as a way to reaffirm national pride and counter iconoclasm.

The presentation of China’s imperial past as a continuous succession is another illusion. Many historical dynasties actually overlapped or coexisted alongside rival states. The histories of non-Han groups and states like the Khitan Liao, Jurchen Jin, Mongol Yuan, and Manchu Qing are often marginalized or contested within mainstream Chinese historiography.

For example, the Qing dynasty is commonly thought to start in 1644 with the fall of the Ming, but it officially began in 1636. Similarly, the dynasty ended in 1912, not 1911 with the rise of the Republic. Such discrepancies highlight how timelines can be adjusted for nationalistic narratives, simplifying or erasing certain facts.

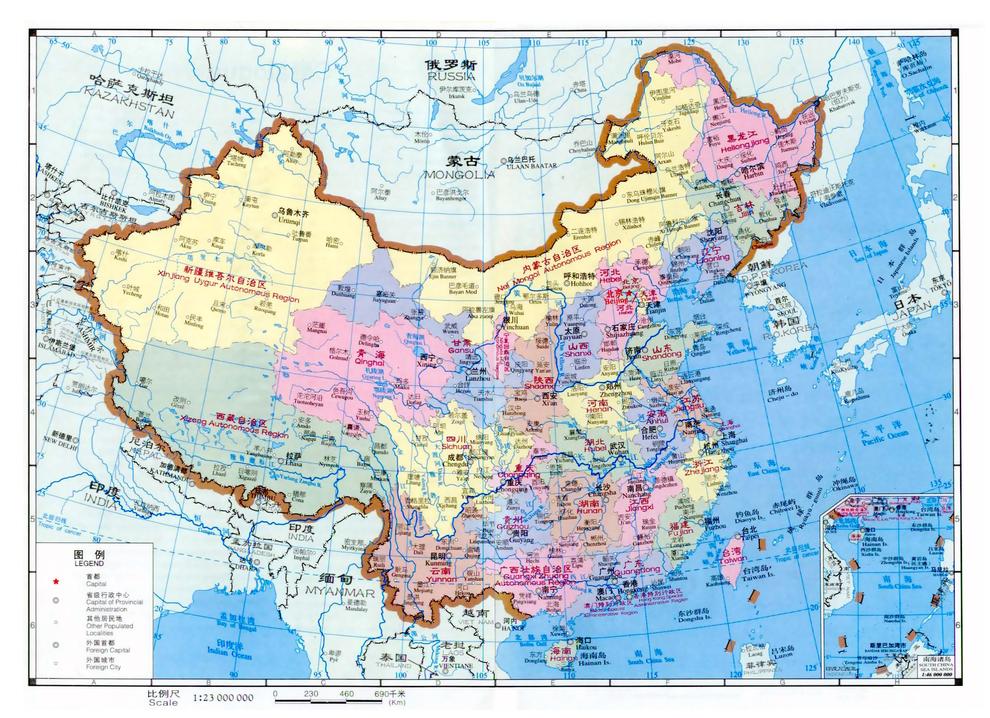

The 5000-year claim focuses almost exclusively on the Han Chinese core region. It neglects the diverse histories of many peoples within today’s China, such as the Sogdians, Tocharians, Tungusic groups, Miao, Hmong, Tai, Zhuang, Tibetans, Mongols, and Taiwanese. Their regional histories do not automatically merge into a single, neat timeline simply because of modern political boundaries.

This selective inclusion supports a narrative that privileges Han Chinese culture and history as the primary national story. The claim of uninterrupted history often serves political purposes, promoting unity while sidelining other identities and local histories.

| Aspect | Reality | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| 5000 years as fixed timeline | Variable; timelines shift with interpretations | History is constructed, not absolute |

| Inclusion of all ethnic groups | Mostly Han-centric history; others marginalized | Excludes diverse regional narratives |

| Imperial succession continuity | Discontinuous, with rival states excluded | Simplifies complex political history |

| Archaeological support | Mixed findings; some validate early texts | Used selectively for political reasons |

The claim of China’s 5000-year history operates as a national myth in the sense that it consolidates multiple, sometimes contradictory, strands of history into one patriotic narrative. It holds symbolic power rather than strict historical accuracy. This narrative legitimizes the People’s Republic of China by invoking an ancient, continuous civilization, despite internal contradictions and the diverse makeup of its territories. This myth has strong cultural and political significance, even while remaining contested among scholars and historians.

- China’s “5000 years” blends facts, myths, and selective historiography.

- Scholarly debates reflect shifts between skepticism and acceptance of ancient texts.

- Political movements, notably the Cultural Revolution, challenged and then reinforced historic narratives.

- Imperial histories often exclude rival states and minorities from the mainstream narrative.

- The historiography privileges Han Chinese history over other ethnic and regional experiences.

Is China’s 5000 Years of History a National Myth?

China’s celebrated claim of having 5000 years of continuous history is, in many ways, more a crafted narrative than a straightforward fact. It paints a glorious picture of unbroken civilization stretching back millennia. But take a closer look, and you find the story is riddled with contestations, reinterpretations, and complex layers of political and cultural reinvention. So, is it a grand, shimmering myth or a grounded historical continuum? Let’s unpack this fascinating debate together.

The Roots of the 5000-Year Claim: A Historical Balancing Act

When people say “5000 years of Chinese history,” they often imagine a seamless river flowing from ancient times into the present. Yet, historians specializing in Chinese history, especially the Qing dynasty, emphasize that this continuity is anything but smooth. For instance, the Qing Empire lasted from 1636 to 1912 — just 276 years — a tiny blink compared to the touted 5000 years.

This alone shakes the foundation of the so-called continuous story. How did we end up with the 5000-year figure in the first place? It’s not a static number; the concept shifted multiple times during the 20th century, with different political agendas pushing the origins of “Chinese civilization” back or forth in time. Where you start counting matters a lot.

Clashing Views: Confucian Tradition, Doubting Antiquity, and Archaeology

Different schools of thought have long debated China’s ancient past. Here are some heavyweight perspectives:

- The Neo-Confucian View trusts early mythic histories. Even though recorded documents only confidently extend back to the Eastern Zhou period (771-256 BCE), it holds that earlier accounts, like those of the Xia and Shang dynasties, contain substantial historical truths.

- The Doubting Antiquity School, born from the New Culture Movement in the 1910s, threw cold water on many of these accounts. They argued that early chronicles were politically patched together and that true history emerges only through critical analysis — not blind trust.

- The Believing Antiquity School

It’s a debate that reflects deeper tensions — between tradition and critique, myth and evidence, nationalism and historiography — and it’s far from settled.

Unexpected Theories: The Sino-Babylonian Curious Case

Here’s a plot twist from history books you might not have heard: The Sino-Babylonian theory proposed in the late 19th century suggested that Chinese civilization actually began as an offshoot of Mesopotamian culture. A French scholar introduced this idea, and Japanese academics passed it to China with some modifications — claiming Chinese mythic ancestors were real Babylonian figures.

This theory clicked with some intellectuals between 1900 and the 1930s but fell out of favor after archaeological evidence showed Chinese culture predates any such migration by centuries.

Fascinating, right? It illustrates how national narratives sometimes borrow from global histories to strengthen or reshape identity stories.

Reinvention in the 20th Century: When History Takes a Backseat

The 20th century was rough and ready for China’s historical narrative. The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), with its radical goal to “start anew,” drastically challenged the idea of a continuous 5000-year civilization. It saw widespread destruction of cultural relics, symbols of “old superstitions,” aiming to rinse away traditional history and values.

Despite failures in practical terms — many relics survived thanks to secret protectors — the intent was clear: to sever China’s historical continuity and construct a new identity tied to communist revolution.

And guess what? This severe upheaval partially explains why the 5000-year story has grown even *stronger* since then. The era’s iconoclasm ironically fueled a potent desire to anchor cultural pride and unity back in deep, ancient roots.

Imperial Continuit&y: More Illusion than Reality

Now, consider what historians call imperial succession. It isn’t the neat chain we often imagine. In reality, empires clashed constantly, and the “winners” rewrote history to present themselves as the rightful heirs.

For example, the Khitan Liao and Jurchen Jin rivaled the Song dynasty but are often ignored in China’s dynastic timeline. The Mongol Yuan and Manchu Qing are controversial too. The Qing dynasty’s official dates — 1644 to 1911 — are even selectively modified; it actually began in 1636 and lasted until 1912. The year 1644 marks the Ming’s fall, not Qing’s rise. These fudgings reveal how historical timelines can shift to fit narratives optimizing “Chinese-ness.”

Whose History Counts? Inclusivity and Regional Narratives

The 5000-year tale predominantly centers on the Han Chinese, the dominant ethnic group. But China today is a gigantic mosaic of regions and peoples with distinct pasts.

Take the Tarim Basin, for example. Its history includes the Sogdians and Tocharians—ancient peoples not traditionally “Chinese” in narrative terms, despite the region now being part of the PRC.

Similarly, Tibet, Mongolia, Taiwan, Manchuria, and various ethnic minorities like the Miao, Hmong, Tai, and Zhuang all have rich, diverse histories often overshadowed or excluded. National history tends to present Han expansion as the central storyline, cleverly eliding these other vibrant narratives.

So, Is China’s 5000 Years of History a National Myth?

It’s complicated. Yes, elements of this claim are mythologized, shaped by political needs, selective storytelling, and historical reinterpretations. But it’s also true that China has an extraordinary and ancient culture with one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations in broad strokes.

Consider the benefits of that 5000-year narrative: it builds national pride, cultural identity, and continuity that strengthens the social fabric. But it can also conceal or erase the messier, more fragmented realities behind history’s smooth surface.

Does that mean the story is entirely false? Not at all. It means it’s a story — powerful, evolving, and sometimes contested. The real truth lies somewhere between national myth and historical fact.

Lessons and Takeaways for Readers Curious About Chinese History

- Question Narratives: Don’t take grand historical claims at face value. History is often shaped by those in power and their agendas.

- Understand the Complexity: China’s past includes fragmented empires, diverse cultures, and contested histories that deserve recognition.

- Appreciate Archaeology: The ongoing discoveries always reshape our understanding and keep history exciting.

- Recognize Multiple Voices: The story of China isn’t just Han-centric. Including other peoples’ histories enriches the bigger picture.

Next time someone casually drops “China has 5000 years of history” at a dinner party, you can smile knowingly and explain it’s not a simple, unbroken timeline but rather a dynamic and sometimes disputed narrative. History is rarely neat—often messy, debated, and surprising. And that’s what makes it truly fascinating.

So, what’s your take? Is history a straight road or a winding adventure? With China’s story, it’s definitely the latter.