Dracula (Bram Stoker, 1897) received moderate success at the time of its publication but did not become an instant blockbuster hit. It sold well, attracted positive critical attention, and remained in print throughout Stoker’s life, yet it gained its full cultural significance only years later through adaptations in theater and film.

Published first in 1897 by Archibald Constable and Company in Westminster, Dracula quickly saw additional editions. Hutchinson & Co. released a colonial edition, and the novel appeared in the U.S. in 1899 via Doubleday & McClure Co. Stoker himself prepared a revised and abridged edition in 1901 to reach a broader readership. In the U.S., the story was serialized in newspapers, helping maintain steady interest. The book stayed continuously in print until Stoker’s death in 1912.

The immediate financial rewards were limited. Despite respectable sales, Stoker did not earn substantial income from the novel. In 1910, his income amounted to £575, with only £166 from literary sources. He faced financial hardship and sought a Royal Literary Fund grant in 1911. Stoker’s financial struggles amid steady sales illustrate that Dracula was not a commercial blockbuster on the scale of some contemporaneous works.

Critically, Dracula achieved considerable acclaim upon release. Arthur Conan Doyle, a respected figure, praised it as “the very best story of diablerie which I have read for many years.” Publications like the Daily Mail and Punch lauded its originality, calling it “the very weirdest of weird tales.” Most reviewers admired its Gothic atmosphere and compared it favorably to classic horror stories like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Edgar Allan Poe’s works.

However, not all reviews were unreservedly positive. The Manchester Guardian critiqued the book’s impact, suggesting modern audiences found it “more often grotesque than terrible.” This view remained a minority but hints at mixed reactions in some literary circles to Stoker’s style or the novel’s themes.

In his efforts to capitalize on the success, Stoker wrote a play version of Dracula. However, it was never staged during his lifetime, existing only as a script reading done to establish copyright. The absence of a theatrical hit or major public event linked directly to the book during Stoker’s life limited its immediate cultural impact.

The novel’s rise to iconic status occurred primarily after Stoker’s death. Florence Balcombe, Stoker’s widow, managed the rights and saw the story’s growing popularity. The unauthorized 1922 German silent film Nosferatu sparked renewed public interest despite copyright conflicts. This step marked an important early moment in the book’s cultural ascent.

Further momentum came from the stage. In 1924, Hamilton Deane adapted Dracula into a play, which was rewritten by John L. Balderston for Broadway. The 1927 production starring Béla Lugosi became a major hit and firmly embedded the character into popular culture. This success inspired Tod Browning’s 1931 film version, again starring Lugosi, a landmark in horror cinema that cemented Dracula’s legacy.

The novel’s journey from moderate late-Victorian Gothic thriller to cultural phenomenon stretched over several decades. It was neither an instant sensation nor a forgotten work resurrected purely through modern reappraisals. Instead, Dracula garnered steady attention, respectable sales, cultural credibility during Stoker’s life, and then exploded into wider fame through adaptations in the 1920s and 1930s. These adaptations shaped how the public remembers it today.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Initial Publication | 1897 by Archibald Constable; US edition 1899; revised edition 1901 |

| Sales and Print | Steady sales; remained in print until Stoker’s death in 1912; serialized in newspapers |

| Critical Reception | Mostly positive; praised by Arthur Conan Doyle and major newspapers; some mixed reviews |

| Financial Outcome | Limited earnings; Stoker had financial difficulties despite book’s success |

| Stage and Film | Unproduced play by Stoker; 1927 Broadway play major hit; 1931 film solidified fame |

| Legacy | Broader cultural impact mainly posthumous through adaptations and legal controversies |

- Dracula had moderate success and steady sales in its initial years.

- It received positive critical attention but was not a runaway hit.

- Stoker struggled financially despite the novel’s presence in the market.

- The novel’s major cultural influence grew decades later through stage and film.

- Adaptations in the 1920s and 1930s transformed Dracula into a cultural icon.

How Was Dracula (Bram Stoker, 1897) Received in Its Time? Was It an Instant Hit or Discovered a Bit Later?

Dracula, Bram Stoker’s landmark novel, was moderately successful at the time of its release but didn’t become the cultural giant we recognize today until years later. Its reception is a fascinating story of steady sales, respectable praise, a bit of financial hardship, and a slow-building legacy that exploded decades after Stoker’s death.

Let’s unpack the details behind this gothic tale’s debut and how it made its mark — trust me, it’s more than just bats and capes!

The Launch: Solid but Not Superstar

Dracula first appeared on the literary stage in 1897, published by Archibald Constable and Company in Westminster. Soon after, another edition hit the shelves courtesy of Hutchinson & Co., aimed at readers across the British Empire’s far-flung colonies. Across the Atlantic, the American crowd got their hands on it in 1899, thanks to Doubleday & McClure Co. A revised and abridged 1901 edition widened the appeal even more.

Stoker worked hard to keep Dracula in print throughout his lifetime — that’s persistence! The novel was also serialized in U.S. newspapers, making it more accessible and hinting at a respectable readership.

But despite this distribution, the book never became a runaway bestseller like some contemporaneous novels. So, should we deem it a success? The answer isn’t black and white; it’s a shade of Vlad’s classic cape—some call it immense success, others say moderate. Either way, the book sold well.

Critical Reception: Vampires Get a Nod (With a Side of Skepticism)

Not all reviews bite, and Dracula was, by and large, well-received. Arthur Conan Doyle, yes, Sherlock Holmes himself, hailed it as “the very best story of diablerie which I have read for many years.” High praise from a master of suspense!

The Daily Mail and Punch chimed in with positive notes, branding the book “the very weirdest of weird tales.” One can picture Victorian readers who loved a good shiver down the spine cheering this on.

Of course, it was not all fang-tastic. The Manchester Guardian voiced a cooler take, suggesting the tale’s effect often veered toward the “grotesque” rather than truly terrifying. A minority viewpoint, but it illustrates mixed feelings about gothic horrors at that time.

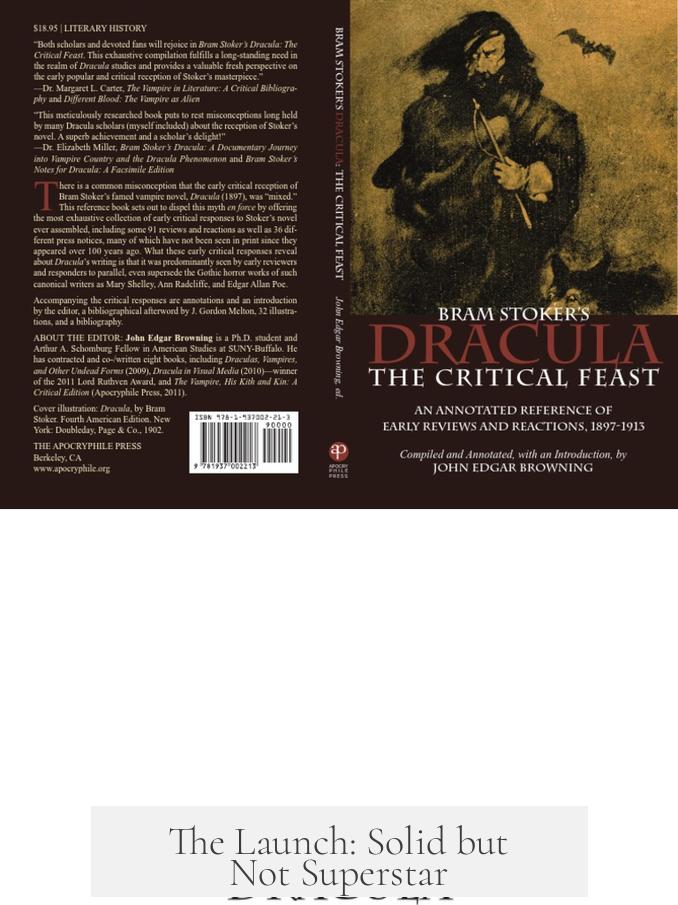

Academic John Edgar Browning later confirmed that Dracula was mostly seen as holding its own or surpassing other great gothic works, like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and Edgar Allan Poe’s stories.

But Did Bram Stoker Get Rich? Spoiler: Not Really

Here’s a twist: despite respectable sales and praise, Bram Stoker himself wasn’t rolling in pounds. His earnings from literature were modest—just £166 out of £575 total income in 1910. That’s roughly equivalent to a humble livelihood, not a Dracula-level fortune.

Stoker even sought support from the Royal Literary Fund in 1911, underscoring his financial struggles. A combination of copyright issues and perhaps limited commercial exploitation hampered his gains.

Trying to Sink Teeth into the Stage

Seeking to capitalize on his novel’s growing popularity, Stoker penned a play adaptation of Dracula in the final years of his life. However, the production never quite left the crypt. It only had a script reading at the Lyceum Theatre, mainly for legal reasons.

No major theatrical success followed during his lifetime. This limited broader public exposure beyond the book’s readership.

The Posthumous Rise of Dracula: When the Novel Became an Icon

If you think Dracula suddenly became a household name after the 1897 release, think again. The novel’s pop culture bite came *after* Bram Stoker’s passing in 1912.

His widow, Florence Balcombe, managed the book’s rights and saw the beginning of Dracula’s resurgence in the early 20th century. The 1922 silent film Nosferatu — an unauthorized and haunting adaptation — stirred public fascination, even though legal action soon suppressed the film.

Then came a major game-changer in 1927: Hamilton Deane’s stage adaptation, rewritten by John L. Balderston for Broadway, starred Béla Lugosi as the bloodsucking Count. This play was a hit, injecting fresh life and excitement into the vampire tale.

Just a few years later, in 1931, Tod Browning’s film version of Dracula, featuring Lugosi again, weaponized the character onto the silver screen. This production cemented the novel’s legacy and influenced generations of vampire lore.

The takeaway? The novel’s broader cultural impact was a slow burn — a mix of steady readership, legal battles, theatrical hits, and cinematic triumphs. It wasn’t an instant sensation, but over time, it embedded itself deeply in our literary and popular imaginations.

What Can We Learn from Dracula’s Initial Reception?

- Steady Success Over Instant Fame: Dracula didn’t storm the literary charts overnight but built an enduring presence.

- Critical Acclaim with Caveats: Most reviewers respected it, but not all were equally thrilled. The story’s weirdness polarized some opinions.

- Financially Tricky for the Author: Stoker wasn’t wealthy from his famous creation, demonstrating the unpredictable nature of literary markets.

- Legacy Through Adaptation: Stage and film versions decades later brought Dracula the fame and cultural grip that the book alone initially missed.

Does this sound oddly familiar? Many books that define genres and inspire countless adaptations don’t find instant success. Sometimes, it’s the cultural ecosystem — films, theater, media — that turns a good story into an immortal legend.

So, if you’re a creator or storyteller worried about overnight success, remember Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Sometimes, the longest shadows cast are from stories that creep in quietly before consuming the world.