Roman citizens were divided into different classes based on ancestry, wealth, and political roles. The main classes included Patricians, Plebeians, Nobiles, Equites, and the Senatorial Class.

The earliest social division in Rome separated patricians and plebeians. Patricians were the descendants of the original founding families of Rome, called patres. These families included well-known clans such as the gens Julia and the gens Cornelia. Plebeians, on the other hand, were those of non-noble descent who came later. This division was significant at first but blurred over time.

During the early Republic, patricians held most political power, angering the plebeians. The plebs pushed back by organizing revolts and withdrawing from the city, demanding political rights. This led to the creation of the Tribune of the Plebs, an office designed to protect plebeian interests, with powerful veto rights. Thus, plebeians gained considerable political power despite their lower birth status.

Over time, the distinction between patricians and plebeians lost practical importance. By the Late Republic, patrician status had become largely honorary and did not guarantee power. Wealth and political success became more important factors for influence.

A separate class called the nobiles, or Roman nobility, arose during the Republic. Nobiles were those who had an ancestor that served as consul, Rome’s highest elected official. This gave families prestige and easier access to elite political positions, especially in the Senate. However, this status was based on family history, not legal privilege, and could weaken as generations passed.

The rise of the equestrian order, or equites, also reshaped Roman social structure. Originally, equites were citizens wealthy enough to maintain a horse for cavalry service. Most equites were wealthy plebeians, and some had more money than many senators. Over time, as commerce grew, more citizens qualified as equites, leading to conflict over political representation.

The Gracchi brothers and later leaders highlighted the demand for equites to gain more political rights. Their struggle was different from plebeian-patrician conflict; it centered on the equites’ desire for higher status and inclusion in power structures like the Senate. Eventually, reforms under Sulla expanded senatorial rights to include some equites, creating a broader nobility class, but also increasing social tensions.

The senatorial class consisted of the senators and their immediate families. Their status came from holding official office and being part of Rome’s governing body. Unlike patricians or equites, senatorial status was not hereditary but depended on political achievement and wealth meeting certain criteria, like property ownership.

| Roman Citizen Classes | Description | Political Role |

|---|---|---|

| Patricians | Descendants of founding families; original noble class | Early Republic power holders; lost exclusive rights over time |

| Plebeians | Non-noble commoners, majority population | Gained political rights; elected Tribune of Plebs |

| Nobiles | Families with ancestral consuls | Senate access; political prestige |

| Equites (Equestrians) | Wealthy citizens able to maintain horses | Roman cavalry; merchants; sought political inclusion |

| Senatorial Class | Senators and families | Official governing class; legislative and executive power |

By the end of the Republic, these classes had overlapping memberships and the old rigid distinctions faded. The aristocratic nobiles and wealthy equites both sought Senate seats. Traditional patrician dominance diminished significantly.

Slaves were not Roman citizens and formed a separate social group with no political rights. Citizenship itself evolved over time, sometimes extended to allies and provincials.

- Patricians were Rome’s original aristocracy but lost exclusive power by the Late Republic.

- Plebeians were the commoners who gained political power through the Tribune of the Plebs.

- Nobiles gained prestige from ancestral consuls and had notable political access.

- Equestrians formed a wealthy class originally tied to cavalry and later commercial wealth.

- The Senatorial class comprised officeholders gaining status from political roles, not just birth.

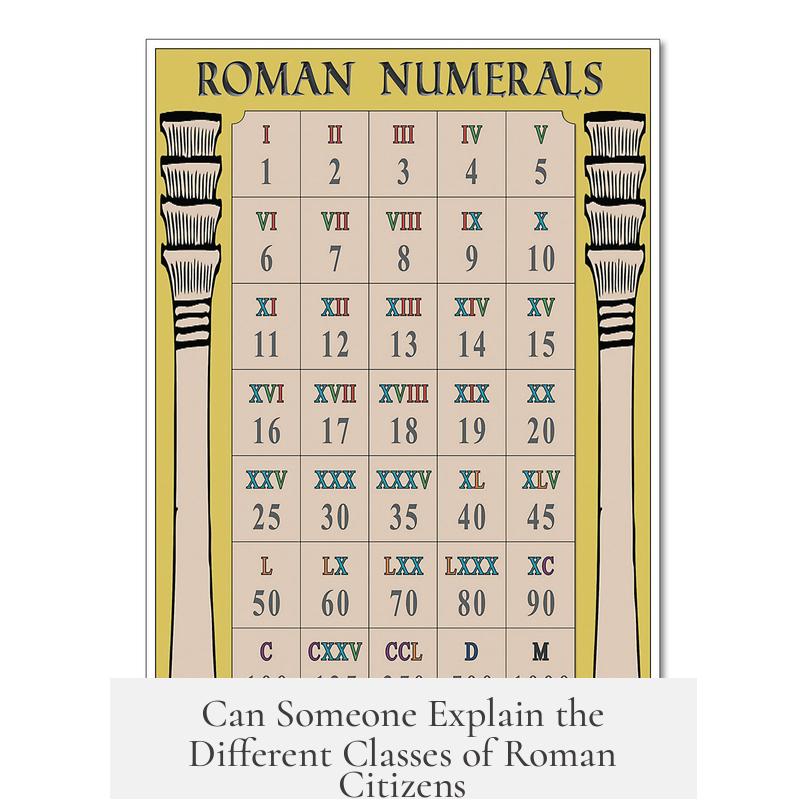

Can Someone Explain the Different Classes of Roman Citizens?

Absolutely! The classes of Roman citizens were a complex web of social, political, and economic statuses that evolved over time. At the heart of it, Roman society was divided among patricians, plebeians, equites, nobles, and senators—each with its own distinct roles, rights, and quirks. Let’s dive deeper and untangle this ancient social spaghetti.

At first glance, it might seem that Roman citizen classes are just dusty history to memorize — but understanding these classes reveals much about Roman politics, social tensions, and power plays. Ready for a mildly funny yet mind-opening time-travel through Rome’s social ladder? Let’s begin.

Patricians and Plebeians: The Original Social Drama

Back in the day, right after the Republic was born, Rome basically had three “classes” —Patricians, Plebeians, and the unfortunate Slaves (not technically citizens).

Patricians were the exclusive founding families, the VIP club. They were descendants of the patres, the original “dads” who founded Rome. Think gens Julia or gens Cornelia. Initially, this gave them high status and major privileges. The twist? There were actually two branches of patricians: the original founders and later noble families from places like Sabine country, such as gens Claudia.

Plebeians, on the other hand, were the commoners. They arrived later and had non-noble roots. Early Rome was a battleground between these two groups. Plebs got fed up with the patricians’ grip on power. So they staged a classic ancient protest: they just wandered off the city! This “plebs walkout” forced the patricians to share power. Plebeians earned the right to elect the Tribune of the Plebs—a powerful magistrate with veto rights over any legislation. Talk about getting a big “Nope!” button.

By the Late Republic, this patrician-plebeian split had practically evaporated into an honorary title game. Once mighty nobles became more symbolic as plebeian families climbed the social ladder.

The Nobiles: Rome’s “Who’s Who” of Power

As time marched on, Rome rebranded its “top dogs” not by pure birth, but by political achievement. Here entered the nobiles—those with an ancestor who had been a consul. This was noblesse oblige at its finest. Having a consul ancestor gave you prestige, connections, and right of passage into important roles.

However, this status depended heavily on recent ancestral glory. A senator whose dad was consul had a leg up on someone with a great-great-great-grandfather in office. It was a social pecking order, but also a flexible one based more on fame than permanent privilege.

Later, Sulla’s reforms bumped the equites into this noble group with senatorial rights, blurring lines further. Eventually, with Caesar and the Julio-Claudian emperors wiping out many nobles, the nobiles distinction lost sharpness.

Equites: The Wealthy Horsemen Class

If you thought Roman society revolved only around politics, think again. Money and horses came into play big time. The equites, or equestrians, started as cavalry—the folks rich enough to maintain horses. Originally, most equites were wealthy plebeians, because patricians preferred officer roles rather than riding around as mere horse soldiers.

With Rome’s economy booming, this horse-owning crowd expanded tremendously. It got so big it was impossible to ignore. Suddenly, equites were not just cavalry—they were the burgeoning merchant class and upper tax-bracket businessmen.

This wealth brought demands for political representation. The bickering between Rome’s populares and optimates groups boiled down largely to this question: who really represents the equites? Sulla and Marius clashed over this, until Sulla ironically enacted reforms championed by his rivals.

Think of equites as Rome’s version of wealthy entrepreneurs or upper-middle-class citizens with big wallets but distinct from hereditary nobles.

Senatorial Class: Power Through Position

What about Senators? This one’s simpler than it looks. The senatorial class wasn’t a fixed social class but a status based on office. If you were a senator, congratulations—you were high society. Your family was, too, by extension.

Senators had specific political roles and influence but held no special birthright outside their position. If you lost your seat, you lost status. This made the senatorial class somewhat fluid compared to patricians or nobles.

What’s the Big Picture?

Roman citizenship and its classes weren’t just about labels. These divisions reflected real tensions, power struggles, and financial realities that defined the Republic’s history. Patricians once ruled the roost, but plebeians rose up and changed the game. Wealthy equites challenged the old power structure, and nobles based their prestige on political success rather than just ancestry.

By the Late Republic, many of these distinctions blurred. Rome grew more diverse, with social class mixing through marriage, military service, and politics.

Why does this matter today? Because it shows that social systems— ancient or modern—are rarely static. Power moves from birthright to wealth to political achievement and back. Rome’s citizen classes remind us that society is fluid, complex, and sometimes hilariously contentious.

Practical Takeaway

If you’re a history buff, remembering Rome’s classes gives you insight into how ancient power worked. For casual learners, it’s a story of rich horsemen, rebellious commoners, and noble families all vying for influence. And for us modern readers? It’s a reminder to never underestimate the power of a good protest (or a mass walkout) to change society.

So next time you hear “patricians” or “equites,” you’ll know it’s not just historical jargon—it’s a fascinating tale of Rome’s social dance.

“Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it whether it exists or not, diagnosing it incorrectly, and applying the wrong remedy.” — Groucho Marx, but certainly true for Roman social classes!