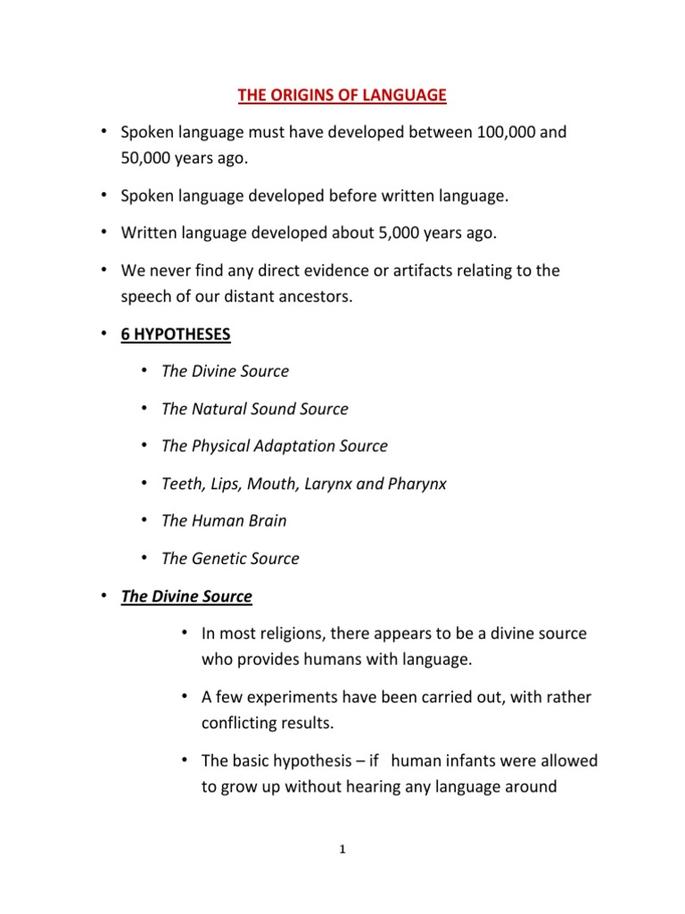

Spoken language likely formed much earlier than any direct evidence can confirm, with estimates ranging from around 2 million to at least 200,000 years ago, aligning with the evolution of anatomically modern humans and possibly their ancestors.

The origin of spoken language remains difficult to pinpoint. There is no prehistoric record of language because writing is the only direct evidence of linguistic use, and writing appeared only about 5,000 years ago. Without written records, scholars rely on indirect evidence such as archaeological finds, genetics, and fossilized anatomy.

Several indirect sources suggest an early development of communication:

- Archaeological artifacts: Symbolic cultural activities like burial rites, jewelry making, and cave paintings imply abstract thinking possibly mediated by language-based social interaction.

- Fossil evidence: Structures such as hyoid bones and braincase casts indicate capability for vocalization in early humans and Neanderthals.

- Genetic studies: Research on genes such as FOX2, involved in speech and language, suggests a long evolutionary history.

Language forms part of a communication spectrum. Many animal species use complex communication that includes elements like intentional deception and structured signals. Some non-human primates display rudimentary grammatical systems. This pushes the boundary rather than defines a clear transition to human language.

In our direct human lineage, behaviors requiring sophisticated communication emerge very early:

- Neanderthals had hearing abilities tuned similarly to modern humans, suggesting sound communication capability comparable to ours.

- Homo erectus, living nearly 2 million years ago, shows signs of complex tool use and social behaviors, implying advanced communication.

- Australopithecus displayed complex communication but it is uncertain if it approached modern language.

Most linguists agree that language evolved well before anatomically modern humans, who appeared about 200,000 years ago. Language is likely a fundamental human trait, supported by:

- Universality: No known human society lacks spoken or signed language.

- Neurological evidence: Specialized brain regions such as Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas are dedicated to language processing.

- Rapid acquisition in children: Language learning follows consistent developmental stages across cultures.

Cases such as the spontaneous emergence of Nicaraguan Sign Language highlight humanity’s intrinsic capacity to develop language even when a shared system does not exist. This supports the idea that language is hardwired into our neurobiology.

The timeline for language development involves some debate. A conservative estimate places the emergence of sophisticated language around 50,000 years ago; however, this is challenged by compelling evidence extending it back much further. Language probably did not start suddenly but gradually evolved through increased complexity along our evolutionary path.

Language and music may have evolved together. Theories propose that early humans used musical sounds and infant-directed speech—such as soothing songs with varying pitch and tone—to communicate emotional states and social bonds before fully developed language arose.

Modern research stresses that spoken language need not resemble today’s speech sounds. Sign languages, which are fully developed languages without vocalization, demonstrate that language depends on patterned variations in communication rather than specific sound ranges. Consequently, debates over anatomical limitations, like the shape of the hyoid bone, do not preclude early language use.

| Aspect | Key Insights |

|---|---|

| Prehistoric Evidence | Indirect: tools, burial, symbols indicate language use |

| Brain Specialization | Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas show language-specific processing |

| Timeline | Likely originated 1-2 million years ago with early Homo species |

| Animal Communication | Complex but lacks full language characteristics; shows spectrum |

| Language Universality | All human societies have a form of language (spoken or signed) |

| Emergence Examples | Spontaneous sign languages demonstrate innate language capacity |

The study of language origins crosses multiple disciplines including anthropology, linguistics, neuroscience, and genetics. Each method has limitations and biases, leading to a range of conclusions. Despite this, converging evidence favors early language use.

Key points to remember:

- No direct prehistoric record of spoken language exists; reliance on indirect evidence is necessary.

- Language likely aligns with the emergence of anatomically modern humans, about 200,000 years ago, or earlier.

- Neanderthals and earlier hominins probably used sophisticated communication akin to language.

- Human brains contain specialized structures crucial for language acquisition and use.

- Language is universal and develops naturally in humans, highlighting it as an intrinsic biological trait.

- Language may have evolved gradually, sharing origins with music and social vocalization.

When Do We Believe Spoken Language First Formed?

Simply put, spoken language likely first formed roughly between 1 to 2 million years ago. This far predates our species, suggesting language evolved gradually over a long evolutionary timeline. While pinpointing an exact moment is impossible, abundant indirect evidence points to this deep antiquity.

Language is not just a quirky human invention. Instead, it’s a deep biological heritage woven into our brains and behaviors across hundreds of thousands of years.

The Puzzle of Pinpointing Language’s Dawn

Trying to identify exactly when the first spoken language emerged is like trying to catch smoke with your bare hands. The main challenge is simple: there is no prehistoric record of spoken language. People didn’t write down their conversations until much, much later. Writing is the earliest direct proof of language, but it only appeared about 5,000 years ago—peanuts on the evolutionary clock.

So, how do experts get around this? They use indirect clues like fossils and archaeological finds. For example, the structure of the hyoid bone—a small bone involved in speech—can hint at vocal capabilities of ancient hominids. Fossilized skulls tell us about braincase sizes and shapes, suggesting brain regions devoted to language. Genetic clues, like the famous FOX2 gene, support human speech abilities. These clues come from anthropology, genetics, and even behavioral studies of close animal relatives.

However, each of these methods holds biases and limits, often sparking debate. Different studies come up with different timelines, often ranging over hundreds of thousands of years.

Language: A Universal Human Trait

One undeniable fact: all human societies use language. There is no known culture without spoken or signed language. Even deaf communities develop fully fledged sign languages spontaneously. For instance, in Nicaragua, deaf children created Nicaraguan Sign Language over just a few decades—no teachers, no instruction, just natural human drive.

Such examples highlight that language is a fundamental property of humans, hardwired into our brains. Children pick up language effortlessly, following universal developmental patterns, implying a biological blueprint.

Cases of language disorders pinpoint language to specific brain areas, mainly Broca’s and Wernicke’s regions. This reinforces the idea that language isn’t a cultural accident but evolved deeply within our biology.

Signs of Language in Our Ancestors

So how far back does language stretch? Anatomically modern humans have been around for about 200,000 years. From the evidence, it’s likely language did too, or something extremely similar.

Beyond that, Neanderthals provide fascinating clues. Their ears were tuned to the same sound frequencies as ours, suggesting they heard and possibly spoke in the same ranges. They crafted complex tools and buried their dead, activities almost impossible without advanced communication.

Diving deeper, the extinct species Homo erectus, dating back close to 2 million years, likely used complex forms of communication. Although opinions vary, increasing evidence suggests they had the cognitive abilities for proto-language.

Less clear is Australopithecus. While they communicated, it’s uncertain whether their communication reached language-level complexity.

The weight of evidence argues against the idea that language only popped up 50,000 years ago—a popular but outdated viewpoint.

Language: Not Just Vocal Sounds

People often get fixated on the sounds we make now. But language isn’t restricted to specific vocal patterns. Sign languages show how richly expressive language can be without noises at all. This weakens arguments that ancient species couldn’t have language because their vocal apparatus didn’t match ours exactly.

Therefore, when tracing back language origins, we must consider broader communication forms rather than just speech sounds.

The Spectrum of Communication: From Chirps to Conversations

Language exists on a spectrum, not a simple on/off switch. Many animals communicate quite complexly. Prairie dogs have alarm calls conveying detailed information. Meerkats use various sounds based on context. Even non-human primates show proto-grammatical patterns in their calls. However, only humans combine high complexity, creativity, and abstraction in language.

Music and Early Language

One intriguing theory suggests language and music developed side-by-side. Imagine prehistoric moms soothing babies with sing-song “infant-directed speech.” This rhythmic, pitch-varying baby talk might have been the seedbed for music and language.

This sing-song style isn’t a modern invention. It’s observed worldwide and seems universal. Could it be that language and music grew from parents cooing to infants? This idea offers a charming peek into language’s emotional roots.

Brain Regions Behind Language

Humans have specialized brain areas just for language. Broca’s region manages speech production, and Wernicke’s handles comprehension. These evolved gradually, beginning long before writing existed.

Reading and writing, in contrast, are cultural inventions so recent they don’t have dedicated brain regions. We have to learn them consciously. Language, however, is absorbed effortlessly as children grow.

Summing It Up: When Did Spoken Language Really Start?

- No direct prehistoric record exists. We rely on archaeology, fossils, and genetics.

- All humans speak or sign language. Signed languages are full languages, proving language flexibility.

- Language likely predates modern humans. Ancestors like Neanderthals and Homo erectus show signs of complex communication up to 2 million years ago.

- Language emerged gradually. It’s a spectrum—no sudden switch.

- Music and early baby talk might have shaped language’s origins.

Given this landscape, it’s reasonable to place the evolution of spoken language somewhere between 800,000 and 2 million years ago. This timeline fits with evidence from our ancestors, brain evolution, and archaeological symbolism.

Why Does This Matter?

Language isn’t just about words. It shapes culture, social organization, and thought itself. Understanding its origins improves everything from anthropology to artificial intelligence.

Plus, it’s pretty fascinating to realize the voices—and perhaps the sing-song lullabies—we hear in our heads today trace back to ancestors who lived alongside mammoths 100,000 generations ago.

Want To See Language’s Origin Through a Different Lens?

Consider this: if language didn’t emerge gradually over millions of years, how else could complex tools, art, and social structures develop? Could Neanderthals have buried their dead meaningfully without language? Could early Homo erectus have coordinated group hunts?

Language evolved as much as a social glue as a communication tool. It allowed early humans and their relatives to plan, share knowledge, solve problems, and pass culture forward—fundamentally transforming our species.

Final Thoughts and Food for Thought

The question “When did spoken language first form?” isn’t just academic. It touches on what it means to be human. We can’t point to a precise moment, but we can acknowledge language is ancient, complex, and entwined with our very brains and bones.

Language likely didn’t appear overnight. Instead, it emerged through countless small steps—perhaps a comforting hum whispered to a restless baby, a crafted symbol etched on stone, or a collaborative hunt signaled by distinct calls. It’s a beautiful story still unfolding as we speak.

So next time you have a chat, consider you might be echoing voices from a million years ago.