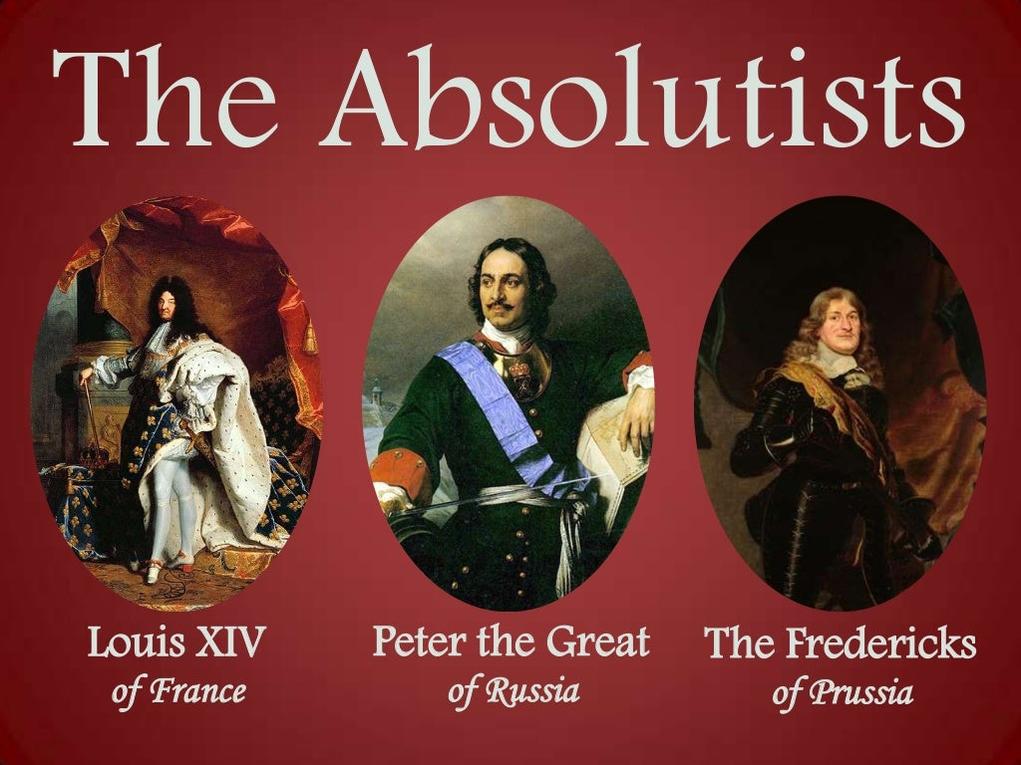

Absolutism refers to a form of political authority where a ruler holds supreme, centralized power. This power is not limited by laws or checks from other institutions. Absolutist monarchs claim total control over the state and its government. This concept is often linked with European rulers from roughly the 16th to 18th centuries, especially France’s Louis XIV.

The meaning of absolutism has evolved over time. Historians debate whether absolutism truly existed as a clear system or if it is a modern label applied retrospectively.

Between 1400 and 1800, European states, particularly in Britain and France, grew stronger. These states extended their influence globally using military and economic power. This period marks the rise of powerful centralized governments. These transformations are the backdrop for discussions about absolutism.

Two main explanations account for these changes in Europe:

- Economic factors: Thinkers like Karl Marx and Friedrich von Hayek argue that capitalism reshaped society, creating new economic relationships that influenced political power.

- Political factors: Max Weber emphasizes the rise of bureaucratic states with structured administrations that replaced personal loyalties and patrimonial rule.

Max Weber’s theory is central to understanding modern statehood and debates about absolutism. He described a shift from patrimonial authority—power based on personal connections—to authority grounded in legal codes and institutions. Weber’s definition of the state involves organized bureaucracy and law-based governance.

However, applying Weber’s framework to early modern rulers is problematic. Past rulers operated under very different conditions. Historians often judge earlier polities by modern standards, calling any competent royal administration a “proto-bureaucracy,” even those from the Middle Ages.

The idea of absolutism emerged largely from studying France and Britain. In Britain, historians like John Brewer highlight the 18th-century civil service as a model for modern bureaucratic government. This British administrative system influenced European ideas about governance.

In France, the concept of absolutism centers on Louis XIV and his minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert. French absolutism is linked to their efforts to centralize power by controlling the nobility and expanding state administration. This model became a key example of absolutist rule.

Traditional accounts depict Louis XIV as a ruler who subdued aristocratic power by enticing nobles to court life at Versailles, stripping them of local authority and replacing it with royal bureaucrats. These narratives position absolute monarchy as a step toward modern statehood and European industrial societies.

Yet, these standard interpretations face criticism. Historian William Beik challenges the simple story of Louis XIV’s absolutism. He argues that the claim French absolutism marked clear progress from feudalism to modernity is overly simplistic. The comparison between France and England often ignores complex differences in their political and economic paths.

Many historians now view absolutism as a contested construct rather than a fixed historical reality. Rather than a uniform system, absolutism involves variations in kingly power, bureaucratic capacity, and the role of aristocracies. It is not simply a progressive stage toward modern states.

| Aspect | Traditional View | Modern Critique |

|---|---|---|

| Centralization | Strong central royal control with nobles stripped of power. | Noble power was reduced but varied regionally; influence persisted in many forms. |

| Role of Bureaucracy | Bureaucratic administration grew as personal rule declined. | Early bureaucracies were limited and often integrated personal relationships. |

| State Development | Absolutism marked progress toward modern state and capitalism. | The process was uneven; absolutism overlaps with feudal and other forms. |

In short, absolutism describes the rule of monarchs claiming near-total power during a transformative period in Europe. Its usefulness depends on recognizing it as a flexible, debated idea shaped by historical context. The rise of strong centralized states connected to economic and political changes sets the scene, but absolutism’s exact nature and role remain debated.

- Absolutism means centralized, unchecked royal power.

- It is linked to European states from 1400–1800 becoming powerful.

- Economic and political explanations debate capitalism versus bureaucratic state roles.

- Max Weber’s ideas on bureaucracy shape modern definitions of statehood.

- Traditional views see French absolutism as advancing modern statebuilding.

- Recent critiques question the simplicity and uniformity of absolutism.

- Absolutism is best understood as a historical construct, not a fixed system.

Can Someone Explain Absolutism to Me? Unpacking a Historical Puzzle

Absolutism is a tricky beast to pin down because it often feels more like a story historians tell than a clear-cut reality. Simply put, absolutism refers to a style of governance where a monarch holds supreme authority, unchecked by other bodies. But here’s the kicker: the idea of absolutism as a neat, uniform system is largely a modern construct—historians often debate what it really meant and if it ever truly existed as traditionally portrayed.

Let’s dig into why this concept puzzles so many and what makes it fascinating beyond royal crowns and velvet cloaks.

Why Can’t Historians Agree on Absolutism?

For over thirty years, scholars have wrestled with the idea of absolutism—not just debating it but actively dismantling it as a tidy concept. How’s that for a plot twist? The challenge is that “absolutism” emerged mostly as a way to explain the rise of strong monarchs in Europe, especially in France and Britain, between the 1400s and 1800s.

Back then, things were changing fast. Nations like England and France forged powerful states, reshaping global politics and economies. Yet, historians today caution that applying modern labels, like “absolute monarchy,” to this era might oversimplify what was going on.

The Big Picture: Europe’s Power Shift (1400–1800)

During this four-century window, European countries gained more power than any state before, laying groundwork for today’s world order. The UK, for example, didn’t just sit on that power—they used it to shape trade, colonization, and even cultural spread.

But what caused such a huge surge in power? Was it the economy? Politics? The short answer is: all of the above, sparking battles among historians with different views.

Capitalism vs. Bureaucracy: Two Sides of the Same Coin

On one side, thinkers like Karl Marx and Friedrich von Hayek argue that economic shifts—basically capitalism rising—powered Europe’s new status. Money talks, and capitalism brought innovation and trade expansion that fueled state strength.

On the flip side, sociologist Max Weber points out that politics played a massive role too. He emphasized the move from “patrimonial authority”—getting power from personal ties and tradition—to authority rooted in legal codes and bureaucracy. Think less “rule by king’s whims,” more “rule through organized institutions.”

Weber’s ideas shape how we define the modern state—think police, taxes, courts. But here’s the rub: applying these modern categories backward in time can be like trying to fit a square peg in a round hole. Medieval kings didn’t have bureaucracies like today, and their “power” looked very different.

The French and British Absolutism: Mirrors and Foils

Traditional history loves to set France and Britain as twin stars in the absolutism saga, but their stories contrast sharply—showing the complexity beneath the “absolutist” label.

- In Britain, historian John Brewer highlights the rise of a “civil service” in the 1700s that streamlined taxation and administration. This is often cited as a prototype for modern bureaucratic states—a subtle but powerful mechanism behind the throne.

- France, on the other hand, has the iconic image of Louis XIV (“The Sun King”) lounging at Versailles, dazzling nobles with grandeur while stripping them of real political power. His finance minister Colbert pushed a bureaucratic revolution, centralizing control, and fueling state growth.

For a long time, this French story gave rise to the neat idea of absolutism: a monarch with total, centralized control, standing above messy feudal powers.

But Wait—Is Absolutism Overrated?

William Beik, writing in 1989, warns us not to take this story at face value. Standard textbooks paint Louis XIV as the ultimate “modernizer” who crushed feudal aristocrats and cleared the path to a bourgeois, capitalist France. But history, as usual, loves its complexities and contradictions.

Beik and other critics argue the story is too linear and simplistic. Absolutism may look like a stepping stone toward modern statehood and democracy, but in reality, it was often messy, contested, and deeply political. Sometimes monarchs compromised; other times they struggled just to keep order.

So, What’s the Takeaway on Absolutism?

If you’re asking, “Can someone explain absolutism to me?”—here it is:

Absolutism is a historical term describing monarchs who held strong central power, but that power was often contested, uneven, and shaped by broader economic, political, and social forces. Modern views, shaped by scholars like Weber and Marx, challenge the idea that absolutism was a fixed or straightforward system, instead showing it as a complex evolution tied to Europe’s rise as a global power.

This means absolutism isn’t just about kings issuing orders. It’s about how power shifted from personal loyalty and feudal chaos toward structured institutions and legal frameworks.

Real World Lessons from Absolutism’s Rise and Fall

Studying absolutism sheds light on how power works today. Bureaucracies, legal institutions, and the balance between authority and liberty don’t appear overnight. They evolve through messy struggles over who holds power and why.

Next time you hear a leader claiming “absolute” control, remember: history warns against absolute anything. The kings of old found it tough to stay on top—even with armies and palaces—because power is rarely that absolute.

So why does this debate matter? Because understanding absolutism teaches us to ask better questions about authority. When does power become tyranny? When does it serve people instead of rulers? And how do political, economic, and social structures shape these outcomes?

Questions to Ponder

- Can we truly separate economic factors like capitalism from political power structures in shaping states?

- How do modern governments compare with early absolutist states in terms of centralizing power? Are we as “modern” as we think?

- What happens when historians use present-day concepts to interpret the past? Do we risk missing the real story?

History isn’t just dates and monarchs. It’s a conversation spanning centuries, inviting us to look deeper and think critically. Absolutism? It’s less an absolute fact and more an evolving idea—a fascinating puzzle that keeps historians on their toes.