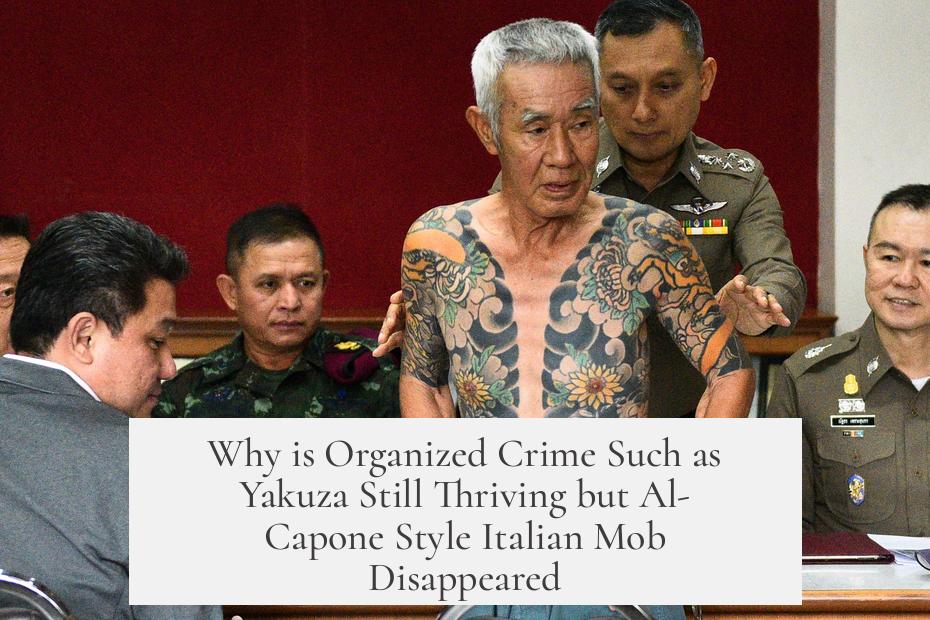

Organized crime like the Yakuza thrives today because it remains intertwined with Japan’s social structure, political system, and community in ways the Italian-American Mafia no longer does in the United States. The Yakuza’s endurance contrasts sharply with the decline of Al Capone-style mobs, which largely faded due to assimilation and legal pressures.

The Mafia originally grew within immigrant communities who faced systemic economic exclusion in the US. Groups such as Italians, Irish, and Jews used crime as alternative means to gain wealth. Over time, these groups integrated into mainstream society and lost the outsider status that fueled organized crime’s necessity. Today, these immigrant groups are largely assimilated and face fewer external pressures that previously sustained mob activities.

Conversely, the Yakuza has deep roots in Japanese history and certain marginalized populations, especially the burakumin caste and ethnic Koreans. Around 70% of members in major syndicates like the Yamaguchi-gumi trace back to burakumin heritage. This long-standing social exclusion creates a distinct environment where the Yakuza fills roles linked to their origins as Edo-period merchants and gamblers, maintaining a unique cultural niche.

Public acceptance differentiates the Yakuza sharply from American mobs. The Yakuza operates openly with headquarters known to the public and authorities. They take part in community activities, such as distributing candy on Halloween and aiding government efforts during the COVID-19 pandemic to limit gatherings. Their visibility and partial acceptance by law enforcement contrast with the Mafia’s underground and highly stigmatized existence in the US.

Politically, the Yakuza maintains strategic ties with right-wing politicians and has historic roles supporting government interests by opposing left-wing movements and providing muscle for political groups. This connection lends a certain legitimacy and influence within Japanese politics. Historically, even the American Mafia had moments of government collaboration, such as during WWII, but such relationships ended without the continuous, embedded political role enjoyed by the Yakuza.

In facts:

- American Mafia faded due to immigrant assimilation and law enforcement crackdown.

- Yakuza stems from marginalized groups not fully integrated into society.

- They operate openly, engaging with communities and authorities.

- Political ties reinforce their influence and survival in Japan.

The combined forces of social integration in the US and legal suppression diminished Italian-style mobs. Meanwhile, Japan’s unique social fabric, political alliances, and cultural acceptance enable the Yakuza’s ongoing presence.

Why is Organized Crime Such as Yakuza Still Thriving but Al-Capone Style Italian Mob Disappeared?

Simply put, the Yakuza thrives today because it is deeply interwoven into Japanese society, culture, and politics, while the Al Capone-style Italian mob lost its footing due to assimilation, law enforcement pressure, and changing social dynamics in America. Let’s unpack this interesting contrast, shall we?

The American Mafia, famously represented by figures like Al Capone, emerged largely from immigrant communities—Italians, Irish, and Ashkenazi Jews—who found themselves outside mainstream society. They were outsiders trying to climb an economic ladder with missing rungs. Organized crime gave them an alternate route to power and wealth.

But here’s the kicker: over time, these groups assimilated into mainstream American culture. Today, Italians, Irish, and Ashkenazi Jews are seen as “typical white Americans.” This assimilation erased many of the external pressures that once funneled them into crime. As a result, the societal environment that fueled old-school mob families quietly faded.

Meanwhile, the Yakuza in Japan stands on a different foundation. These groups often recruit from marginalized communities such as the ethnic Koreans and burakumin—an outcast caste historically discriminated against in Japanese society. The burakumin connection is quite significant; as reported in the 1986 book Yakuza by David Kaplan and Alec Dubro, about 70% of members in the Yamaguchi-gumi—the largest syndicate—trace their roots to this caste.

Think of the Yakuza’s origin story as rooted in the merchant class, specifically the tekiya and bakuto, types of traders and gamblers from Japan’s Edo period. This lineage gives the group a historical legitimacy and a sense of embeddedness in Japan’s societal fabric that the American mob lacked.

Speaking of societal integration, Yakuza groups are not the shadowy, hidden mobs that Hollywood often portrays. Japanese authorities openly know their headquarters, and the public sees some of their community participation. You might be surprised, but Yakuza members hand out candy during Halloween and even helped government efforts to prevent COVID-19 spread. That’s right—they actively collaborate with officials to maintain social order.

“Even working with government to stop during the COVID pandemic to avoid gatherings to spread the disease,” as reported by Asahi News.

This visibility contrasts sharply with the secretive nature of the American Mafia, which has often been driven underground by heavy law enforcement and public disdain.

Yakuza also engage in spectacular displays of power—remember the 2014-2016 gang war that featured a 100-car parade in Toyama? That level of open showmanship signals a confidence in their standing within society and sends a clear message to rivals.

Politics adds another layer to this difference. The Yakuza have deep ties to right-wing political figures in Japan and have historically acted against left-wing groups, effectively serving as muscle for far-right factions. They even provided bodyguard services for U.S. President Eisenhower during his 1960 Japan visit, thanks to connections with Liberal Democratic Party supporter Yoshio Kodama. This direct involvement with political power provides them protection and leverage.

Contrast that with the American Mafia’s political connections, which were often covert and transient. Sure, during World War II, they helped the government for mutual benefit, and CIA links to Mafia figures in the 1960s are well-documented, but such collaborations never translated into open societal acceptance. Instead, federal law enforcement ramped up crackdowns, systematically dismantling the mob’s power bases.

So, what can we learn from this? The Japanese societal and political environment tolerates and even embraces the Yakuza to some extent, seeing them as part of the system. Their public image is paradoxical—they’re criminals yet community fixtures, sometimes contributing to social order. In contrast, the American Mafia lost the outsider status that justified its existence. As these immigrant communities integrated and law enforcement targeted them aggressively, the old model collapsed.

Want to picture the difference succinctly? Imagine the Italian mob as a nightclub bouncer who got kicked out of the club after the guests changed their style and the club’s security tightened. The Yakuza, on the other hand, runs a long-established tavern on the main street, openly advertising with a neon sign, respected by regulars, and on friendly terms with the local police. It’s a blunt analogy, but it hits the point.

Practical Insights for Observers and Readers

- Assimilation and acceptance matter: Groups that become part of the mainstream tend to lose their “outsider” allure, causing old-style organized crime to fade.

- Societal tolerance is a double-edged sword: When a society unofficially accepts organized crime, its endurance increases, as seen with the Yakuza.

- Political connections protect longevity: The Yakuza’s ties to political factions help insulate it from eradication.

- Visibility breeds legitimacy: Yakuza’s open activities contrast with secretive mobs, allowing it a quasi-legal existence in Japan.

So next time you watch a gangster movie, ponder this: The Italian mobs of the Prohibition era thrived on exclusion and repression—both societal and legal. When those conditions changed, so did the mob. The Yakuza? They adapt and endure through acceptance, tradition, and politics. Fascinating, isn’t it?

If you want a thrilling story of survival that blends crime, culture, and politics, the tale of the Yakuza is the one to watch—even if it means candy at Halloween and muscle against left-wing rebels.