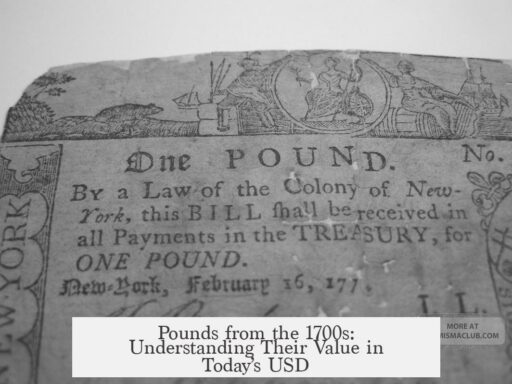

How do Pounds from the 1700s translate into USD today? The value of pounds from the 1700s compared to modern US dollars varies greatly depending on the method of conversion. Estimates range from about $80 to $4,000 per pound, illustrating the difficulty in making a precise equivalence.

Determining the modern value of Colonial American pounds is complex. Prices and economic conditions have changed drastically since the 18th century. Direct conversions using raw numbers ignore these shifts, so analysts often rely on comparisons of goods, labor wages, or indexed values. All approaches have significant limitations.

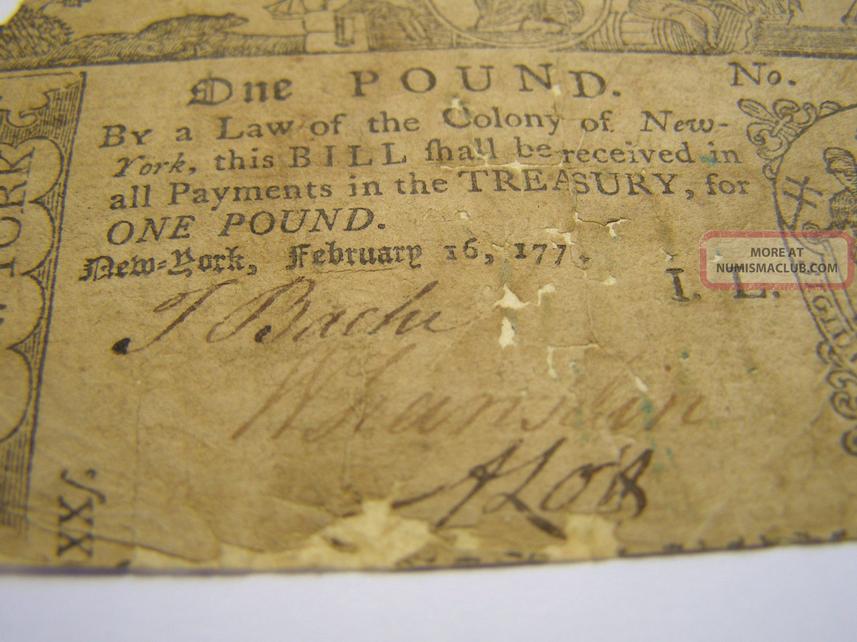

One way to estimate is by comparing the cost of household items recorded in probate inventories to their modern equivalents. For example, Valentine Bird’s 1680 inventory in North Carolina notes he owned three pairs of fine Holland bed sheets, each costing 50 shillings (2 pounds 10 shillings), and a bedstead valued at 8 shillings. Today, a similar four-poster bed from Pottery Barn might cost around $1,600, and a good quality sheet set about $200.

This approach generates dramatically different conversion rates depending on the item used as a benchmark. Using the bedstead price yields a conversion of roughly 1 pound equals $4,000 today. Conversely, the sheet set index suggests only $80 per pound. This vast difference reflects historical changes in the relative cost of goods. Textiles like fine sheets were expensive before mass production, while furniture like bedsteads could be made locally at lower cost.

| Conversion Method | Value of 1 Pound in USD (Today) | Value of 31 Pounds in USD (Today) |

|---|---|---|

| Bedstead Index | $4,000 | $124,000 |

| Sheet Set Index | $80 | $2,480 |

| Indexed Conversion Website (UWyo) | $189 | $5,859 |

Another tool to estimate conversion applies historical currency value indexes. One such index, from the University of Wyoming website, places the 1700 pound at about $189 in 2015 dollars. For comparison, Reverend Parris’ 31 pounds would convert to approximately $5,859 using this index.

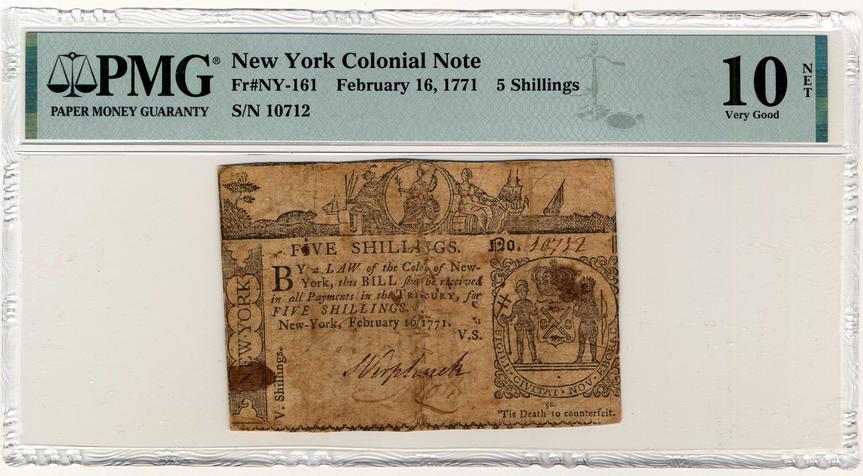

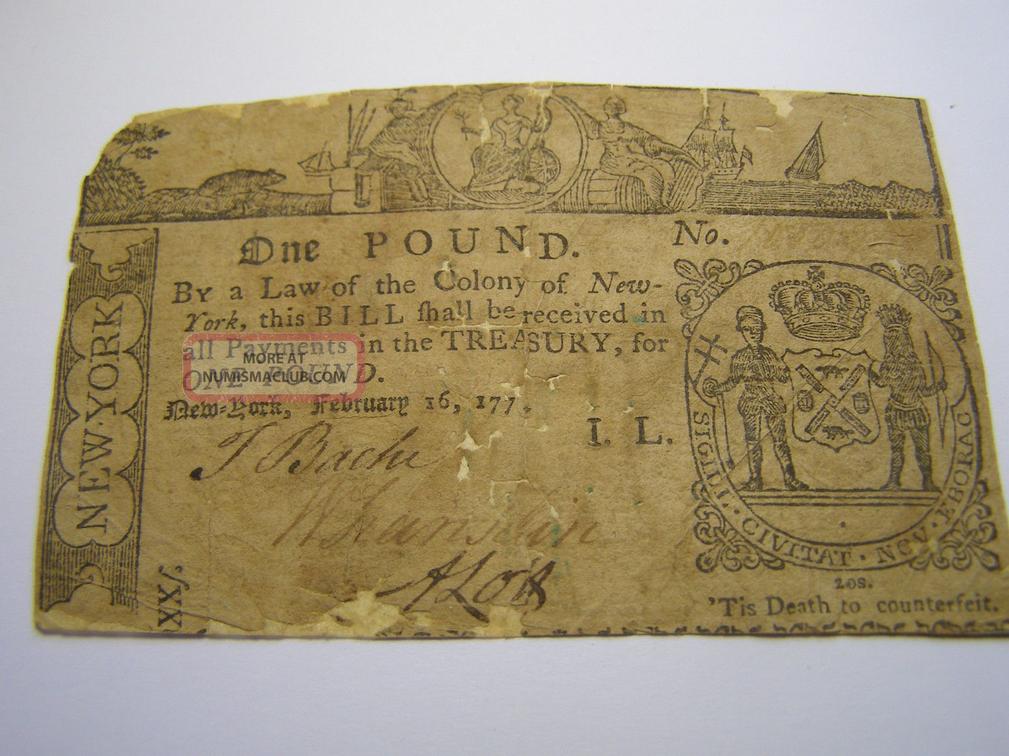

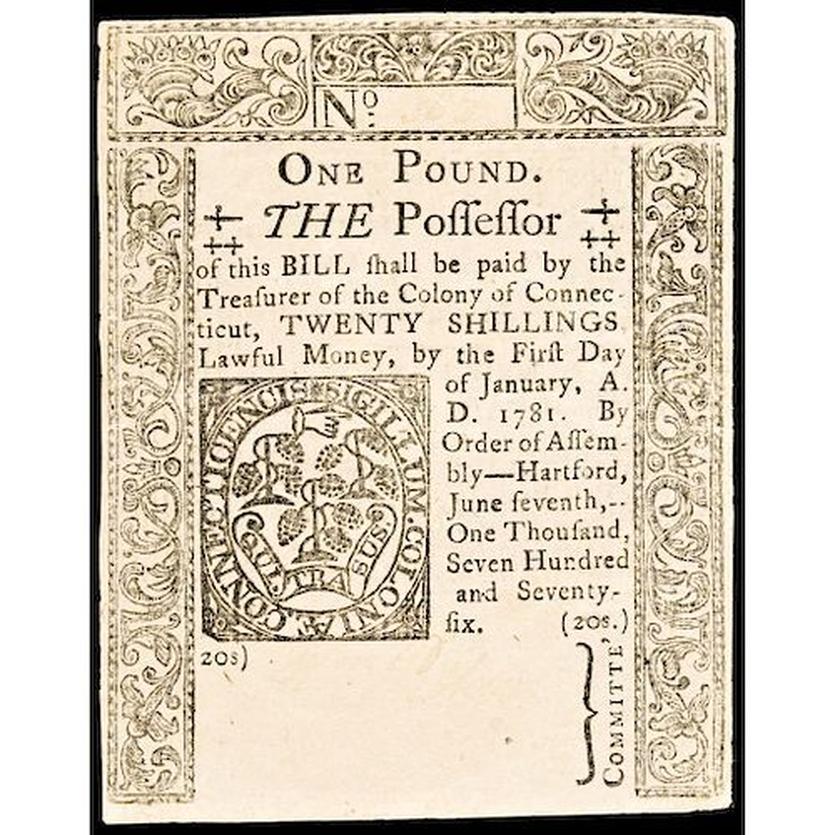

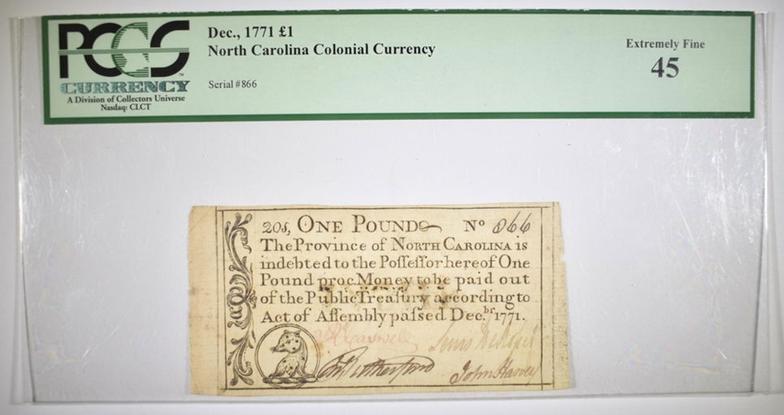

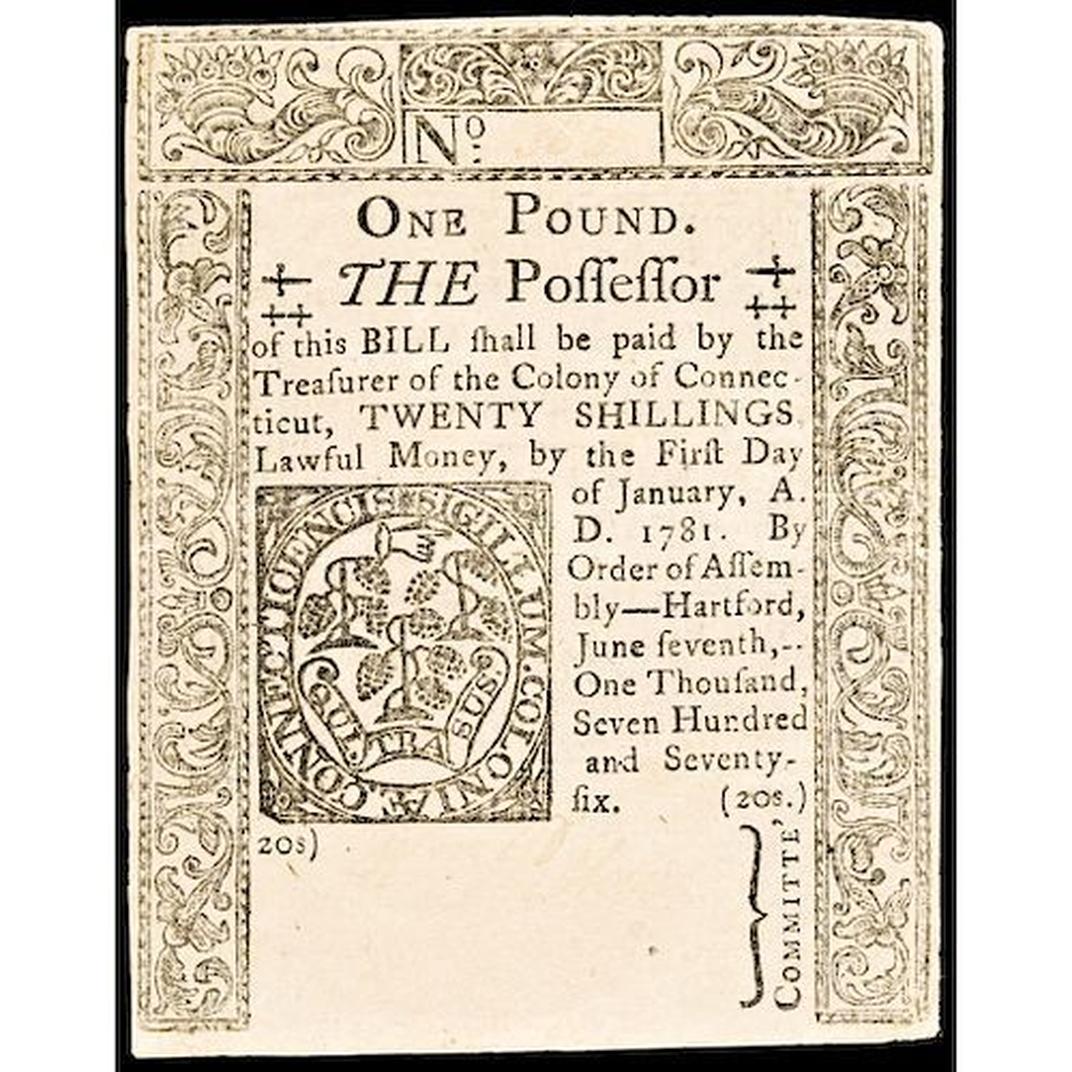

Even these indices have caveats. Colonial currency was not uniform. The colonies dealt with a shortage of specie, using a mixture of English pounds, Spanish coins (notably the eight reales), and their own paper currencies. These local currencies often traded at premiums, and their values varied significantly between colonies.

For example, in 1694, £133.66 in Massachusetts currency equaled £100 sterling, while £100 sterling was worth £129.16 in New York currency and £135.86 in Pennsylvania currency. These discrepancies complicate direct currency conversion.

Moreover, the colonial economy functioned largely on credit. Over 90% of transactions involved credit rather than cash. Promissory notes and informal bookkeeping were common, further muddying attempts to translate nominal pound amounts into fixed modern values.

Labor wages provide another comparative metric. In 1696, a field laborer earned about £7 over six months locally. A male servant might earn £12 annually. Therefore, £31 represented over twice an unskilled male laborer’s yearly income. Translating labor wages based on current minimum wage or living standards can offer a rough gauge of monetary value, but this too varies by region and period.

The challenge in translating pounds from the 1700s into today’s dollars lies in these economic complexities. Goods prices varied, local currencies fluctuated in value, and credit was paramount. No single conversion method perfectly reflects the economic reality of either era.

- Estimates range widely, from about $80 to $4,000 per 1700s pound.

- Comparisons depend on goods prices, currency indexes, or labor wages.

- Colonial currency was often decoupled from British sterling values.

- Credit-based transactions limit direct currency comparisons.

- All conversions remain rough estimates rather than exact calculations.

How Do Pounds from the 1700s Translate into USD Today?

In short? Pounds from the 1700s don’t translate neatly into today’s US dollars. Depending on what you compare, one colonial pound could be anywhere from $80 to a whopping $4,000 in today’s money!

Let’s unpack why this simple question has no simple answer—and how history, economics, and good old-fashioned common sense come into play.

The Challenge: Comparing Apples to Apples (or Pounds to Dollars)

Imagine trying to compare the price of a fancy colonial bed to a modern mattress. Sounds tricky? Exactly. The colonial economy operated on very different rules and realities than today.

Goods and services had wildly different relative values than today. Some items like textiles were extremely pricey before industrial production made them common and affordable. Others, like furniture, could be made locally, changing their market dynamics.

So, any attempt to convert pounds from the 1700s to USD requires choosing a reference point — and that choice impacts the result radically.

Goods-Based Examples: Beds and Sheets Tell Different Stories

Take Valentine Bird’s probate inventory in 1680 North Carolina. He had three pairs of Holland bed sheets, costing 2 pounds 10 shillings each, and a bedstead worth 8 shillings.

Fast forward: a Pottery Barn four-poster bed similar to Mr. Bird’s bed costs about $1,600 today. And a Pottery Barn sheet set goes for around $200, although it includes pillowcases that Bird’s sheets lacked.

From this, analysts create different “indexes”:

- Bedstead index: 1 pound converts to about $4,000 today.

- Sheet set index: 1 pound converts to around $80 today.

This massive difference shows how the relative cost of goods has changed drastically. Beds could be crafted from cheap local wood, so their prices didn’t inflate like textiles, which were expensive pre-industrial revolution.

What About Indexed Currency Conversion Tools?

There’s also the clever website from the University of Wyoming, which attempts a more general index conversion. It suggests that 1 pound in 1700 would equal about $189 in 2015 dollars.

Applied to Reverend Parris’ 31 pounds, this model values his holdings at nearly $5,859. However, this number suffers the same fate as the bed and sheet examples: it’s a rough guide, not gospel.

Every conversion is a ballpark; pick your reference, and the numbers jump around quite a bit.

The Colonial Currency Circus: Why So Messy?

Unlike today’s centralized currency, colonial money was, frankly, a jungle gym of confusion.

- Shortage of specie: Colonies often didn’t have enough hard currency (silver or gold coins) because they ran persistent trade deficits with England.

- Different coins in play: Surprisingly, the most common coin was the Spanish eight reales. Local governments, like Massachusetts, even printed their own bills (think early government bonds) that promised more value for taxes paid.

- Decoupling of values: Colonial pounds didn’t always match British pounds in worth—regional variations existed. For example, in 1694, £100 sterling equaled different amounts within Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania.

- The credit-driven economy: Astonishingly, over 90% of transactions weren’t cash but credit. Folks used promissory notes and IOUs, often paying debts many months later.

In short, money wasn’t just money; it was entwined with social credit, barters, and localized values. Trying to map that directly to USD is, as they say, “not a walk in the park.”

Labor as a Proxy: How Much Work Did £31 Represent?

A more human angle—how did pounds relate to wages? In 1696:

- A field laborer earned about £7 over six months.

- A male servant earned £12 per year.

- A female servant earned £7 per year.

Therefore, £31 was over twice what an unskilled male worker would make annually. If we frame colonial pounds as labor value, Reverend Parris’ 31 pounds represented a significant sum—akin to a salary multiple.

Summary Table: The Many Faces of a Colonial Pound

| Conversion Method | Value of 1 Pound in USD Today | Value of Reverend Parris’ 31 Pounds in USD |

|---|---|---|

| Bedstead Index | $4,000 | $124,000 |

| Sheet Set Index | $80 | $2,480 |

| Indexed Conversion Website | $189 | $5,859 |

Conclusion: Why Your Answer May Vary Wildly

Converting pounds from the 1700s to today’s dollars feels a bit like chasing ghosts. The powder keg of economic factors—changing prices, wild currency exchange rates, heavy reliance on credit, and fluctuating labor values—makes it impossible to pin an exact number.

So, what’s the takeaway? Any amount you see quoted is a well-educated guess rather than a science experiment. For example, if someone says a pound then equals $4,000 today, ask “Based on what measure?” And if they say $80, wonder “Is that for textiles or furniture?”

Want a practical tip? When reading about historical money, consider the context: what did the money buy, who earned it, and where was it spent?

Navigating the wild world of colonial currency and its modern worth reminds us—history isn’t about neat equations. It’s about stories, people, and the value they placed on everyday things.

1. How can we estimate the value of colonial pounds in today’s dollars?

We compare prices of goods like sheets and bedsteads from the 1700s with their modern equivalents. Different goods give widely different values. Indexed websites offer rough conversion estimates too.

2. Why do estimates of 1700s pounds in USD today vary so much?

Costs of goods changed differently over time. Textiles got cheaper after industrialization, while furniture stayed relatively affordable. Colonial currency was complex, with varied values across colonies, complicating direct comparison.

3. What does £31 from 1700 represent in today’s money?

It depends on the method. Using the bedstead index, it could equal $124,000. Using sheet prices, about $2,480. Indexed websites suggest around $5,859. This range shows how tricky conversion is.

4. How did colonial currency differences affect pound values?

The colonies often lacked official British coins. They used Spanish coins and local paper money with variable premiums. These variations caused pound values to differ between colonies and from the British pound sterling.

5. Can labor wages help translate colonial pounds to today’s money?

Yes, comparing wages helps. For example, £31 was over twice what an unskilled laborer earned in a year. This gives insight into the purchasing power of pounds beyond just goods pricing.