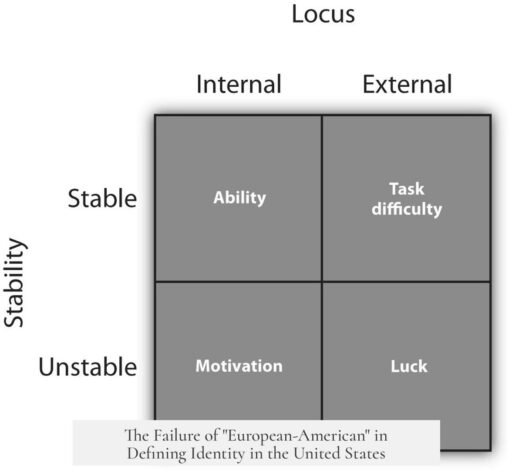

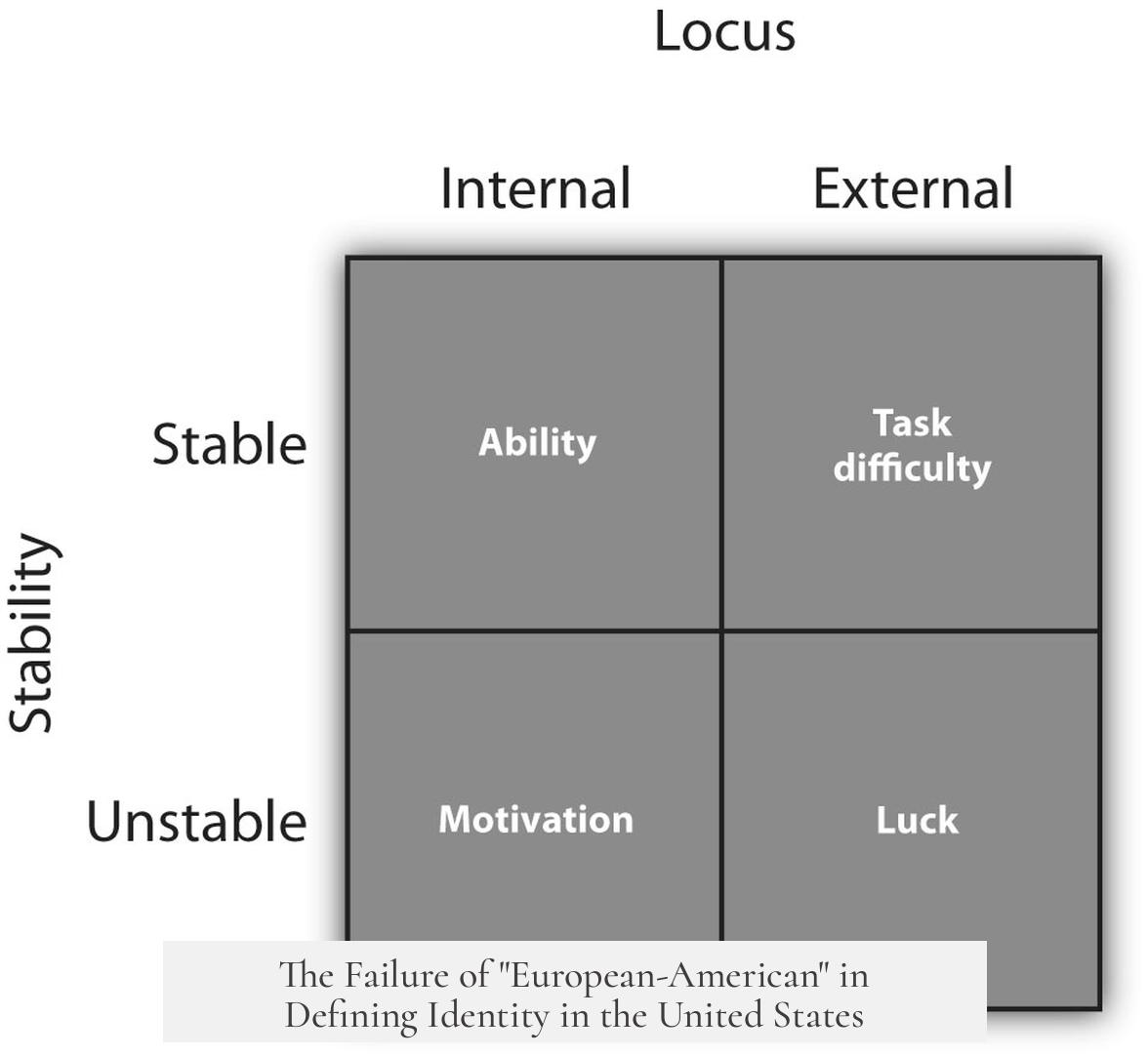

The term “European-American” never gained traction in the US largely because American identity was historically shaped around a narrower concept of whiteness tied to Anglo-Saxon Protestant backgrounds, rather than a broad pan-European heritage. This identity formation created a framework that limited who qualified as truly “American,” especially during periods of immigration that challenged the existing social order.

In the 19th century, the dominant American identity was that of the White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP). This was less about strict ethnic lineage and more about cultural and social markers that conveyed power and belonging. The WASP identity conveyed a sense of racial and cultural superiority. Being American meant belonging to this group, which often excluded other European immigrants who did not fit this mold.

Large waves of immigrants came from Germany, Ireland, Southern, and Eastern Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries. These groups were often seen as threats to the established order. For example, Irish Catholics and Southern and Eastern Europeans were viewed negatively and excluded from mainstream definitions of Americanness. They were often referred to by specific national origins rather than a collective European identity. This showed the lack of a unified pan-European identity within the US at the time.

Immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were often described as less desirable, and their Catholicism set them apart from the Protestant majority. This idea that whiteness alone did not guarantee full acceptance reinforced the importance of cultural and religious factors in defining “whiteness.” Even if ethnically white, many newcomers were not seen as fully “White” in the social sense tied to the WASP ideal.

- WASP identity went beyond skin color and encompassed religion, language, and cultural practices.

- New immigrant groups retained their own traditions and communities, fostering “hyphenated” identities such as Italian-American or Polish-American.

- This was viewed as a refusal to fully assimilate, which fed the fears of these groups being un-American.

At the turn of the 20th century, the idea of “100 Percent Americanism” emerged, emphasizing a singular American identity rooted in White Anglo-Saxon Protestant values. This concept actively rejected hyphenated ethnic identities and was popularized by groups like the Ku Klux Klan. It underscored that being “American” was not just about being white but being the “right” kind of white, aligned with Protestant Anglo-Saxon culture.

Moreover, there was little attachment or identification with Europe as a unified source of identity. The dominant group associated America culturally and historically with Anglo-Saxon Protestant origins, including English, Scottish, Irish Protestants, and later some Northern Europeans. Although other European immigrants were white, their shared European heritage was not enough to create a united European-American identity, except often as a contrast to non-white groups, such as Asian immigrants.

Anti-Asian immigration sentiment, especially against Chinese immigrants, played a key role in broadening the social concept of whiteness. It solidified an in-group defined against an out-group. Political rhetoric at the time linked the American republic’s strength to “the white European race” — but again, this was a selective whiteness that privileged certain European groups over others.

| Factor | Impact on “European-American” Term |

|---|---|

| Dominance of WASP identity | Centered American identity on Anglo-Saxon Protestant culture, excluding other Europeans |

| Immigrant exclusion and skepticism | Southern and Eastern Europeans excluded from full American acceptance |

| Rejection of hyphenated identities | Resisted ethnic qualifiers like “European-” in favor of singular “American” identity |

| Low pan-European identification | Lack of unifying European identity within US immigrant groups |

| Anti-Asian agitation | Reinforced racial boundaries, consolidating selective whiteness |

The term “European-American” did not become common because America’s majority culture constructed “American” differently. It emphasized a narrower cultural and racial identity rather than a broad continental heritage. The ongoing division within European immigrant groups and the pressure to assimilate into a dominant WASP ideal undercut any unified European-American label.

The sociopolitical context shaped these dynamics. Defining “American” often meant exclusion of those considered culturally or religiously different, even if ethnically European. Hence, while many Americans have European roots, the label did not gain traction as a primary identity marker in the US.

- “American” identity was shaped by racial, religious, and cultural factors centered on WASP norms.

- European immigrant groups faced exclusion despite shared whiteness, undermining pan-European solidarity.

- Resistance to hyphenated identities promoted a singular American identity aligned with specific European origins.

- Broad European identity was weak and fragmented within the US context.

- Anti-Asian sentiment helped define whiteness but did not unify Europeans under one term.

Why did the term “European-American” never take off in the US?

The surprising answer: the term “European-American” never gained traction because American identity has long been shaped by a limiting idea of whiteness — specifically, a White Anglo-Saxon Protestant (WASP) ideal — rather than pan-European identity. Sounds like an identity crisis wrapped up in history’s complicated coat, right? Let’s unpack how the U.S. got here and why the “European-American” label just didn’t stick.

Whiteness Wasn’t Just About Skin Color

From the nation’s early days, the word “American” carried an unspoken default: white, Protestant, and Anglo-Saxon. It wasn’t just about race in the simple sense of skin tone, but the entire cultural, political, and social package the so-called WASPs brought with them. This identity dominated much of the 19th century.

Imagine a 19th-century dinner party. The guest list? “Real” Americans only—white, Protestant, and with roots tracing back to England or Northern Europe in some way. Got German or Irish ancestors? Sorry, your invitation might be lost in the mail. This wasn’t blatant racism with no filter, but a cozy monopoly on what being “truly American” meant. The “Anglo-Saxon” label carried an ironic kind of racial superiority. It wasn’t just about where you were from; it was about which European lineage got to define the American line.

Why “European-American” Failed: Too Much Diversity, Too Little Unity

Europe is huge and diverse, and that was part of the problem for “European-American.” The term tried to lump together a wildly diverse set of cultures: Italians, Poles, Irish Catholics, Germans — and that’s just scratching the surface. But for many people, especially WASPs, lumping all Europeans together under one pan-European umbrella felt inaccurate and even threatening.

The big wave of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe coming into the U.S. in the late 19th and early 20th centuries challenged the previously dominant Anglo-Saxon model. These newcomers often carried different religions (mostly Catholic or Eastern Orthodox) and distinct traditions. Instead of embracing them as a broad European family, existing “Americans” preferred to keep drawing sharper boundaries.

This exclusion often disguised itself in “polite” disdain: immigrants were called the “refuse” of Europe. Even if labeled “white” technically, they weren’t considered truly White, not with a capital “W.” They were seen as the wrong kind of white.

The Stronghold of “100 Percent Americanism” and the Rejection of Hyphenated Identities

Fast forward to the 20th century, and this attitude morphed into a cultural push known as “100 Percent Americanism.” This concept screamed, “No hyphenated Americans allowed!” It was about shedding that immigrant label altogether, with a clear message: you’re either fully American or… well, you’re not.

Imagine the heat this created for Italian-Americans, Polish-Americans, or Irish-Americans clinging to their cultural roots. The term “European-American” blurred these distinctions in a way many thought was unrealistic or undesirable. Why? Because “American” didn’t just mean coming from Europe; it was a badge reserved for a select few – the Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority.

The Klan might get some blame for pushing 100 Percent Americanism, but it was a widely shared ideology through much of society. The pressure was clear: assimilate fully or remain the “other.”

Anti-Immigrant Sentiment Helped Cement “WASP” Identity

Not only did internal views shape the term’s failure, but reactions to perceived outsiders also played a huge role. Asian immigrants faced serious hostility — the anti-Chinese agitation in the late 19th century locked in the idea that “whiteness” was the line dividing “us” from “them.”

This made the WASP identity more defensive and less inclusive. It wasn’t just about skin color. It was about culture, religion, and lineage. Europeans outside the “right” group—those from the South and East—were often excluded despite their “whiteness” on paper.

The Lack of European Identification Among Americans

Even if you logically think, “Aren’t all Americans from Europe originally?” the truth is, many Americans didn’t identify strongly with *Europe.* Their connection was to cultural subgroups within Europe—English, Scottish, Irish Protestants, and later, Germans and Nords. The idea of a unified “Europe” identity was thin, fragile, or missing altogether.

Without this shared identity, calling oneself “European-American” felt redundant and unfamiliar. For many, it was almost a foreign idea in itself. The Europe they recognized was fragmented, and the emphasis was always on a narrow Anglo-Saxon heritage.

So… What’s the Big Takeaway?

The idea of “European-American” never caught on because it failed to overcome a deep-rooted and highly selective idea of American identity. American identity was built around a limited definition of “whiteness” anchored in Anglo-Saxon Protestantism. If you didn’t fit that mold, even if your skin was white, you were another “other” who might eventually become American but never by adopting a pan-European label.

Could America embrace “European-American” today? Maybe. But historically, it was too broad and too diverse to function as a unifying identity in a country obsessed with defining who counts as “real” American. It was easier, and more culturally and politically convenient, to keep lots of smaller, mutually exclusive ethnic identities and preserve a narrow center of power and privilege.

Interesting Food for Thought

- Do you identify as “European-American”? Or do you prefer your specific “Italian-American” or “Irish-American” label?

- How do you think identities evolve when the dominant culture changes?

- Will the future see a stronger pan-European American identity? Or is “American” enough?

Understanding this history gives us insight into why identity labels matter—and why some catch on faster than others. The history of “European-American” isn’t just about words, but a story of power, exclusion, and the blurry borders of belonging.