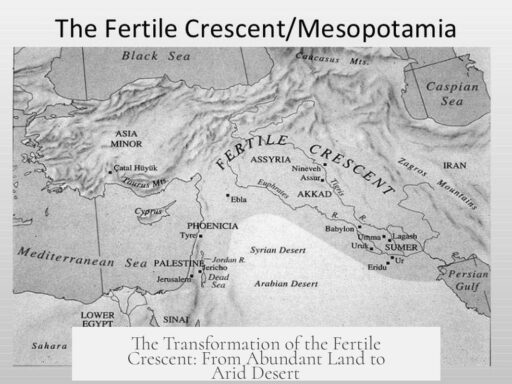

The Fertile Crescent is not a desert but a region that has always been arid with localized fertile areas, especially around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Over millennia, climate changes, human activities, and environmental shifts have altered its landscape, leading to expansion of desert-like conditions in parts of the region.

The Fertile Crescent refers to a crescent-shaped area in the Middle East where early civilizations developed. It includes parts of modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, and Egypt. This region has significant desert areas, but also river valleys and floodplains that remain fertile.

Originally, the Fertile Crescent had more extensive wet and green lands, especially during the Ice Age. At that time, the climate was cooler and wetter, allowing Mediterranean rains to penetrate far inland. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers flooded larger areas, supporting more abundant vegetation. The desert mainly covered the Arabian Peninsula’s dry interior back then.

However, over the last 6,000 years, the climate has gradually gotten hotter and drier. Mediterranean rainfall has decreased and retreated closer to the coast. This has caused the fertile coastal zones and floodplains to shrink substantially. The surrounding steppe and upland forested areas have diminished. As a result, desert conditions have expanded in various parts.

- Rising temperatures and reduced precipitation decreased soil moisture.

- Floodplain size and fertility shrank with less frequent and smaller river floods.

- Vegetation cover on uplands declined, lowering land stability.

Human actions intensified this natural desiccation process. Early farmers and civilizations dug extensive irrigation canals to expand cultivated land. But improper irrigation caused soil damage. Arid soils often have high alkaline minerals like sodium and calcium, which become toxic to plants when irrigation is poorly managed.

Shallow canals kept water near the surface, fostering alkali accumulation around roots, harming crops and leading to increasing soil salinity. Recurring invasions and social upheaval led to loss of irrigation knowledge, worsening soil degradation.

Deforestation upstream of the Fertile Crescent reduced tree cover that stabilized soil and influenced rainfall patterns. Without forests, topsoil washed away during rains, making floods more violent but less nutrient-rich. Over time, soil erosion lessened the fertility of the plains downstream, accelerating desertification.

Livestock grazing, especially by sheep and goats, also contributed. Overgrazing removes vegetation cover, exposing soil to erosion and reducing its capacity to retain moisture. Poorer societies often overgraze lands to meet immediate food needs, sacrificing long-term soil health.

| Factors Contributing to Desertification | Impact |

|---|---|

| Climate Change (6,000 years) | Hotter, drier conditions reduce rainfall and fertile zones |

| Poor Irrigation Practices | Soil salinization and loss of arable land |

| Upstream Deforestation | Soil erosion; reduced nutrient flow downstream |

| Overgrazing | Vegetation loss and increased erosion |

Despite these challenges, parts of the Fertile Crescent remain productive where water is available. The Tigris and Euphrates still sustain agriculture in river valleys. Modern water management aims to mitigate salinity and soil loss, but environmental and social pressures persist.

To summarize key points:

- The Fertile Crescent has always been partly desert, with fertile pockets near rivers.

- Ice Age climate was wetter; since then, drying and warming reduced fertile land.

- Improper irrigation caused soil salinization, damaging agriculture.

- Upstream deforestation increased soil erosion and reduced floodplain fertility.

- Overgrazing removed protective vegetation, accelerating land degradation.

- These combined factors expanded desert-like conditions, reducing overall fertility.

Understanding this history clarifies why the Fertile Crescent is not simply a fertile region turning into desert but a complex environmental mosaic changing under natural and human influences.

Why is the Fertile Crescent now desert?

The short answer: The Fertile Crescent wasn’t exactly a lush paradise that turned into a desert overnight. It has always been a patchwork of fertile strips woven through a predominantly arid landscape. Natural climate shifts combined with human activities—like irrigation missteps, deforestation, and overgrazing—have intensified aridity, shrinking those green pockets and making the region much drier.

Now let’s unpack this fascinating story that stretches back thousands of years. Spoiler alert: it’s not a straightforward tale of green land suddenly waving the white flag and turning into sand dunes.

A Patchwork Landscape, Not a Desertified Eden

The name “Fertile Crescent” evokes images of abundant crops and flowing rivers but it’s crucial to understand that this region has long been a mix of fertile zones amid a vast dry Middle East. It’s not that the Fertile Crescent transformed from a fertile wonderland to desert. Rather, it was always a crescent-shaped stretch of relatively lush land hugged by deserts.

Think of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers as green ribbons slicing through the Arabian desert’s brown canvas. The Mediterranean rains do their best to push inland, but they peter out about 100 kilometers from the sea, leaving much of the interior arid.

This means that when people ask, “Why is the Fertile Crescent now desert?” a fair answer is: because most of the Middle East has always been desert; the Fertile Crescent highlights the few fertile patches where agriculture and early civilizations flourished.

The Climate Rollercoaster: Ice Ages and Dry Spells

Over the past 25,000 years, the region has experienced dramatic climate swings. During the Ice Age, it was cooler and wetter. Picture this: Mediterranean rainfall stretched further inland, the Tigris-Euphrates flooded larger areas, and deserts snuggled only deep inside the Arabian Peninsula.

However, post-Ice Age, the climate got hotter and drier. The Fertile Crescent shrank as floodplains dwindled, the Mediterranean’s wet reach shriveled, and highland woodlands thinned. The steppe zones nearly disappeared. This ongoing aridification made farming trickier but also nudged humans to innovate—prompting early civilization through the need to secure reliable food supplies.

In short, declining environmental productivity helped kickstart civilization—because people had to work smarter to survive.

Irrigation: A Double-Edged Sword

Humans built canals to channel water farther and widen their agricultural reach. Sounds smart, right? But here’s the catch: irrigation in arid zones needs expert care. Soils already high in minerals like sodium start to accumulate salts near plant roots if water isn’t managed properly.

When canals are shallow or poorly maintained, salts bubble up and harm crops, causing soil degradation. Wars, invasions, and social disruption wiped out experts who understood how to maintain these irrigation systems carefully. Without their knowledge, irrigation practices worsened, hastening soil salinization and desertification.

This shows us how human ingenuity can backfire without stewardship. Irrigation once expanded fertility but ended up damaging the very soils it sought to nourish.

Deforestation: More Than Just Missing Trees

What happens upstream influences downstream. Deforestation in the highlands triggered a domino effect: trees help create rainfall by seeding clouds, so their loss led to less rain. Without tree roots, topsoil washed away during floods. Instead of gentle, nutrient-rich floods fertilizing the plains, these floods became violent and stripped away precious nutrients.

This created a vicious cycle: less rain plus soil erosion meant dropping fertility and increased aridity, further shrinking the fertile zones.

The Horns of Overgrazing

Sheep and goats, those notorious grazers, have had a controversial role. Overgrazing removes the protective plant cover, leaving soil bare and vulnerable to wind and water erosion. The outcome? More desert-like conditions.

Socioeconomic realities play their part here. Poor farmers and ranchers struggle to balance immediate food needs with long-term land health. When hunger stares you down, safeguarding land for the distant future feels like a luxury. So, repetitive grazing pressures the land, accelerating desertification.

This means the story of desertification interweaves natural climate tendencies with human survival struggles, showing the complex cause-and-effect web.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

- The Fertile Crescent is not a former lush paradise turned desert, but a zone of pockets of fertility within a largely arid Middle East.

- Climate shifts over millennia have naturally reduced fertile areas, making the region hotter and drier.

- Human activities—especially irrigation mismanagement, deforestation, and overgrazing—have worsened natural aridity, feeding into a cycle of desertification.

- This degradation especially hit the historic floodplains of the Tigris and Euphrates, key cradles of early civilization.

Understanding these factors gives fresh perspective beyond the tired narrative of “fertile land lost to desert.” It teaches the value of careful land and water management when working in fragile landscapes. It also underscores how climate shapes human history and, in turn, how human choices influence the environment.

Looking Ahead: What Can Be Learned?

Can lessons from the Fertile Crescent help combat desertification today? Absolutely.

Restoring upstream forests could improve rainfall and stabilize soil. Smarter irrigation techniques can keep soils healthy and productive. Managing grazing pressures sustainably helps maintain plant cover and prevent erosion. Combining these efforts can help communities persist even as the climate pressures mount.

So, next time someone wonders why the Fertile Crescent is now a desert, remind them: it was never quite the Garden of Eden. Instead, it’s a story of a harsh environment giving rise to civilization through resilience and adaptation—while still wrestling with the timeless challenges of water, soil, and survival.