Pharaoh is seemingly used as both a title and a name due to its origin as a metonym for the Egyptian king’s “great house,” which evolved into a royal title, and its later occasional appearance as a proper name in inscriptions and biblical narratives. This dual use reflects linguistic, cultural, and narrative functions rather than consistent personal naming.

The word “Pharaoh” originates from the Hebrew פַרְעֹה (par‘oh), itself borrowed from the Egyptian phrase 𓉐𓉻, which means “great house.” This phrase originally referred to the royal palace or institution rather than the individual monarch. In linguistics, calling the king by “great house” is a classic example of metonymy: a figure of speech where an associated item stands for something else. Similar to how “The White House” denotes the U.S. President, “pharaoh” referred indirectly to the king by naming his palace. This usage started long before any biblical texts were composed and persisted throughout Egyptian history.

In ancient Egyptian and its later stages, the word’s evolution continued. For instance, in the Coptic language, the king is called ⲣⲣⲟ (rro), with the definite article ⲡ (p) attached, forming ⲡⲣⲣⲟ (prro). This shows the linguistic continuity where the term maintained its link to rulership and kingship.

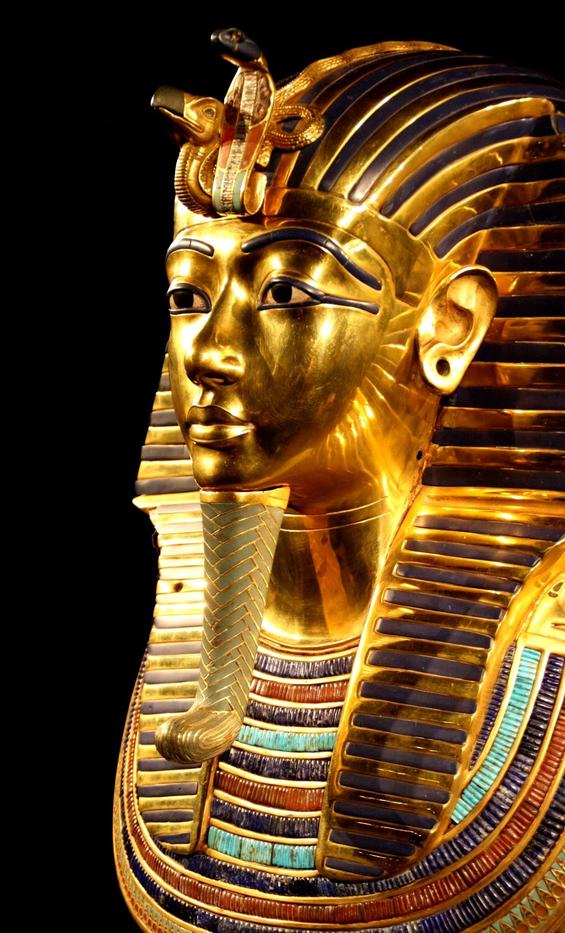

While the dominant function of “pharaoh” was as a royal title, there is documented evidence of its use as a proper name. Notably, on the Temple of Dendur housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, cartouches—royal name inscriptions—contain only the word “Pharaoh.” This exceptional usage, happening long after the time frame of the biblical Exodus narrative, suggests symbolic or formalized naming rather than normal practice. Usually, Egyptian monarchs are identified by personal names or throne names inside cartouches rather than by the term “pharaoh” alone.

The biblical use of “Pharaoh” demonstrates a third function. The Hebrew Bible, especially the Exodus story, employs “Pharaoh” as a proper name for the Egyptian king opposing Moses and the Israelites. Yet, this use is more literary and cultural than historical. The story’s author likely borrowed the Egyptian term to anchor the narrative in Egypt for readers. The focus is not on identifying the specific ruler historically but on casting “Pharaoh” as a generic royal antagonist. Thus, the word’s role here is a narrative convention, adding authenticity and color. The term’s usage reflects the story’s nature as an oral legend or charter myth rather than a record of precise historical events.

To clarify, the term “Pharaoh” is:

- Originally a royal title derived by metonymy from “great house.”

- Primarily used to refer to kings collectively or institutionally.

- Occasionally found as a proper name on some Egyptian monuments, usually for symbolic reasons.

- Employed in biblical Hebrew as a generic name for Egypt’s king, serving the narrative purpose rather than precise identification.

This layered use results in the perception that “Pharaoh” is both a title and a name. But fundamentally, it started as a title and remains so in most historical contexts.

| Usage Context | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Ancient Egyptian Title | King by metonym (great house) | Used from Old Kingdom onwards |

| Proper Name (Exception) | Symbolic use in cartouches | Temple of Dendur inscriptions |

| Biblical/Hebrew Text | Name standing for egyptian king | Exodus narrative |

Understanding this duality requires recognizing the distinctions among linguistic borrowing, symbolic inscriptional practices, and literary storytelling. Each layer shows a legitimate but different application of the term “Pharaoh.”

- Pharaoh originates as a metonymic title, meaning “great house.”

- It mainly denotes the king as an institution, not an individual name.

- Rare instances present Pharaoh as a proper name on monuments.

- Biblical use borrows the term as a name for storytelling purposes.

- The dual usage arises from these different historical and cultural functions.

Why is “Pharaoh” Seemingly Used as Both a Title and a Name?

Pharaoh is primarily a title, not a personal name, but over time its use blurred lines, making it seem like a name as well. This dual usage puzzles many. So what is going on here? Let’s unravel the story behind “Pharaoh” and why it dances between being a grand title and a proper name.

From “Great House” to King

The word “Pharaoh” actually comes from the Egyptian phrase meaning “great house.” Imagine calling a ruler not directly but by their spectacular palace or household. It’s like referring to a president as “The White House” instead of their personal name. This is a classic example of metonymy—a figure of speech where a thing is called by something closely related.

In Egyptian, this phrase stood for the king or ruler himself. The connection is logical: the “great house” is the king’s seat of power, so the phrase became shorthand for the person in charge. This linguistic trick appeared long before the famous Exodus tale was ever told.

Pharaoh as a Title—A Linguistic Tradition

Pharaoh started firmly as a title, not a name. Imagine everyone at a royal court calling their ruler “Pharaoh” in reverence—like saying “Your Majesty.”

The use of “Pharaoh” as a title is deeply rooted in Egyptian language and customs. Even in Coptic, a later Egyptian language, the word for king, rro, and with the definite article became prro, mirroring this tradition of naming rulers by titles associated with their house or status.

This usage persisted well into the long and complex history of Egypt. There was no need to bother with personal names in many contexts, especially when the institution of kingship was more important than the individual.

When Pharaoh Becomes a Name

Here’s where things get a little quirky. Despite being a title, there are clear examples where “Pharaoh” is carved into stone as a name.

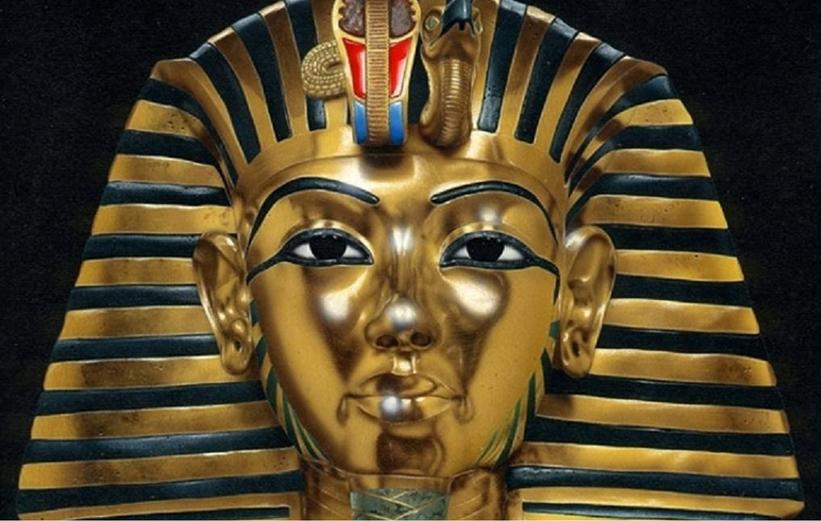

Take the Temple of Dendur at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Inside, you find cartouches—these are oval royal nameplates—with just the word “Pharaoh” written inside. That’s a proper name in Egyptian hieroglyphics. It’s pretty much like someone named “President” on their birth certificate.

This isn’t the norm. It’s a later phenomenon, after the traditional use of Pharaoh as a title. Scholars believe it was symbolic or exceptional, maybe an honorific, rather than standard practice.

Pharaoh in Biblical Hebrew Storytelling

You may be wondering why the Bible uses Pharaoh like it’s a personal name. Easy: the Hebrew Bible borrowed the term from Egyptian, but the story itself doesn’t specify the king’s exact identity.

In the story of the Exodus, the “Pharaoh” features as a character but is more a symbol of the oppressive Egyptian king than a pinpointed historical figure. The tale is an oral legend rather than exact history. The name “Pharaoh” situates the story in Egypt without bothering with historical accuracy.

Using the authentic Egyptian word sprinkled a touch of ancient flavor on the tale, much like a storyteller might drop in foreign names to make their story feel real. It’s a storytelling device. The focus isn’t on who Pharaoh was, but what he represented.

So What’s the Bottom Line on the Dual Usage?

- Pharaoh began as a title, referring to the king via his grand household, not his given name.

- In rare cases, especially later in Egyptian history, Pharaoh was used as a proper name, as seen in the Temple of Dendur inscriptions.

- The Bible uses Pharaoh as a name but really borrows the title to lend historical context and cultural authenticity, without naming a particular individual.

Why Should You Care?

Well, understanding this clarifies how language and storytelling shape our view of history. We often think of Pharaoh as a name—like “King Tut” or “Ramses.” But it is far more nuanced. It’s a title that tells us about ancient Egyptian society and how stories traveled across cultures.

Ever wonder why no one has definitively identified the “Pharaoh of the Exodus”? The answer lies partly in this confusion between title and name. Since the biblical story didn’t care about pinpoint accuracy, Pharaoh stays an anonymous archetype, a stand-in for the idea of Egyptian kingship itself.

Practical Takeaway for History Buffs and Story Lovers

When you watch documentaries or read stories: remember that “Pharaoh” is a title. If you see it written like a name, check when and where.

For example, the cartouches at the Temple of Dendur showing “Pharaoh” as a proper name are exceptions, not the rule. So don’t be surprised if historians talk about specific pharaohs by their unique names (like Ramses, Akhenaten, or Tutankhamun) but also use “Pharaoh” to mean “king” in a general sense.

Next time you hear “Pharaoh,” picture a grand ancient house, a powerful ruler, and the blend of history and myth that carried that word across millennia.

Curious questions to ponder:

- How do titles evolve into names in other cultures?

- What other historical titles have taken on the same double life as “Pharaoh”?

- Could the ambiguity of “Pharaoh” have helped oral traditions keep stories vivid without tying them to specific rulers?

Language is alive. The story of Pharaoh reminds us that words, titles, and names are more than labels. They are keys to unlocking culture, power, and storytelling across time.