The claim that the Olmecs were Africans mainly arises from Afrocentric theories advanced by Ivan van Sertima in his 1976 book They Came Before Columbus. These theories suggest that ancient Africans influenced or founded Mesoamerican civilizations, pointing especially to the colossal Olmec heads as evidence. However, experts widely reject such claims because they rest on outdated racial science, lack archaeological and genetic support, and simplify complex cultural histories.

Van Sertima popularized this thesis by highlighting perceived similarities between Olmec sculptures and African physiognomy, such as lip and nose shapes, suggesting direct African contact or origin. This aligns with a long-standing tradition—tracing back over a century—of attributing Indigenous American achievements to external, often African or Old World, sources rather than Indigenous peoples themselves. This phenomenon is well-documented in literature critiquing Eurocentric narratives that historically minimized Native American cultural complexity.

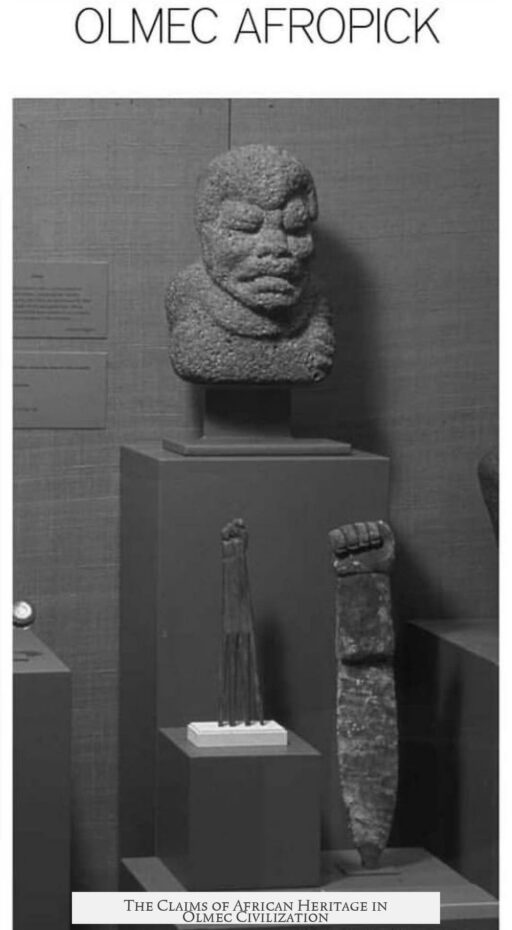

Criticism of these claims focuses on multiple fronts. First, no credible archaeological evidence indicates African artifacts or sustained contact in Mesoamerica during Olmec times. The notable Olmec colossal heads are stylized art forms. Archaeologists caution against interpreting art as literal portraits; sculptures often emphasize symbolic or ideological features rather than realistic ethnicity.

Second, genetic studies tracing Indigenous American ancestry consistently confirm migrations from Siberia across the Bering land bridge, with no genetic markers connecting ancient Mesoamericans to African populations. A 2017 genetic study published in PLOS Genetics confirms this Beringian origin.

Third, physical anthropology dismisses claims based on skeletal comparisons to preconceived racial categories, which are now understood as scientifically invalid. Features linked to climate, such as nose shape, are environmental adaptations rather than racial markers.

Underlying the persistence of the African Olmec theory is a sociopolitical context. Afrocentrism emerged in the 1970s from African and diasporic scholars seeking to reclaim African history erased by colonial narratives. Some Afrocentric interpretations overgeneralize a “black culture,” projecting modern racial notions onto ancient peoples. Critics argue that such approaches sometimes replicate outdated, 19th-century racial typologies under new guises.

Van Sertima’s work, while politically motivated to empower African-descendant communities, at times employs methods and assumptions from earlier colonial anthropology, undermining its credibility. The appeal lies partly in their simplification—offering “secret truths” challenging mainstream history and affirming African contributions to civilization worldwide.

The phenomenon also reflects a broader neglect of African and Afro-descendant histories in the Americas. For example, Afro-Mexican figures like Estevanico and Gaspar Yanga represent African presence in Mexico after the Spanish conquest. Yet, this history remains largely marginalized in scholarship and public awareness. The urge to rewrite history to include Africans prominently in pre-Columbian contexts may partially stem from this erasure.

Finally, the debate often suffers from applying modern racial or ethnic categories retrospectively. Ancient Mesoamerican identities were diverse and fluid, making simplistic racial assignments inaccurate. The Olmecs were a distinct Mesoamerican culture, with their own languages, customs, and developments. Linking them exclusively to African origins misrepresents their cultural heritage and the archaeological record.

Key points:

- The African Olmec theory gained traction mainly from Ivan van Sertima’s Afrocentrist work but lacks supporting archaeological or genetic evidence.

- Olmec art is symbolic and not a reliable indicator of racial identity; physical features like nose shape reflect environmental adaptation.

- Genetic studies confirm Indigenous American origins via Beringia, with no African genetic links to ancient Olmecs.

- Afrocentrism arose to reclaim marginalized African histories but sometimes overgeneralizes or misapplies racial concepts.

- The theory persists partly due to sociopolitical motives, filling gaps left by historical erasure of African contributions in the Americas.

- Modern racial categories do not accurately apply to ancient peoples; the Olmecs represent a unique Mesoamerican civilization.