The Mali Empire under Mansa Musa did not produce more monumental architecture largely due to the political, economic, and cultural priorities of the time, rather than a lack of resources or capability. Understanding this requires examining the historical context and the nature of available evidence.

Historians face challenges when exploring why certain actions were not taken historically, especially monumental constructions. Counterfactuals—what might have happened—are difficult to prove. People living in the period lacked foresight and comprehensive information. What seems like an obvious opportunity today may not have appeared feasible or necessary then.

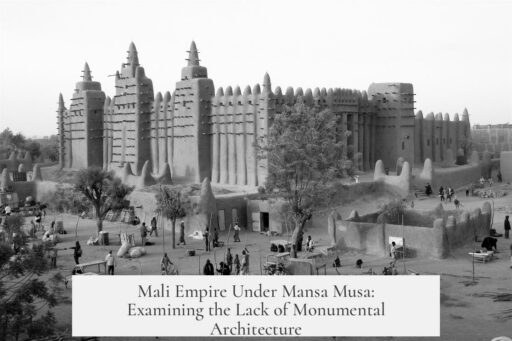

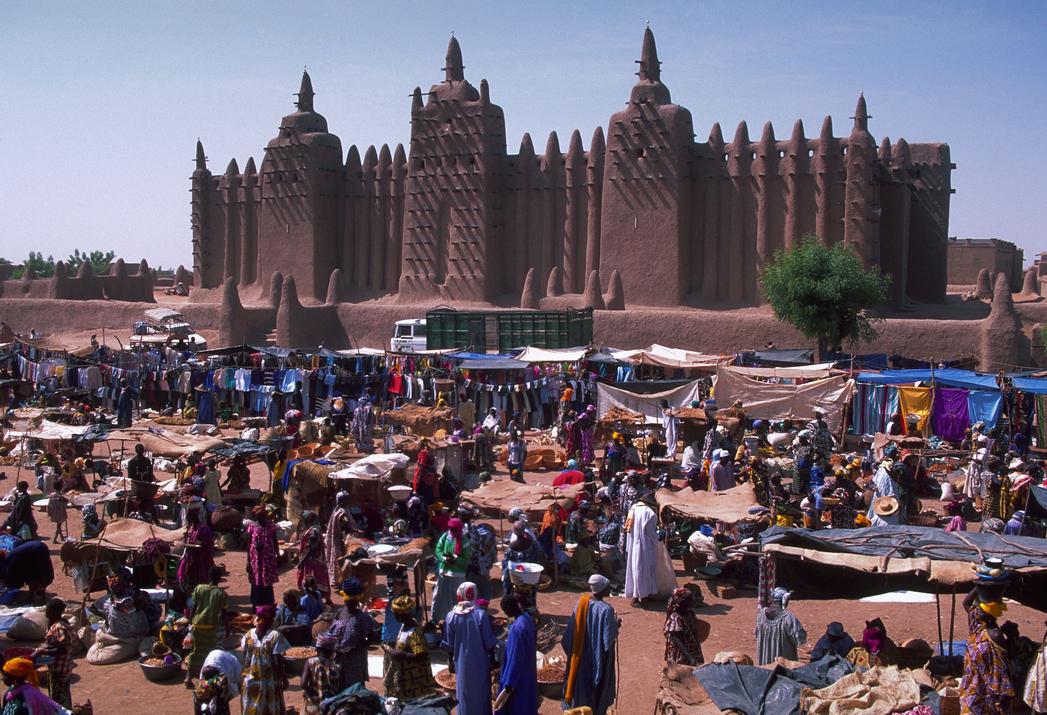

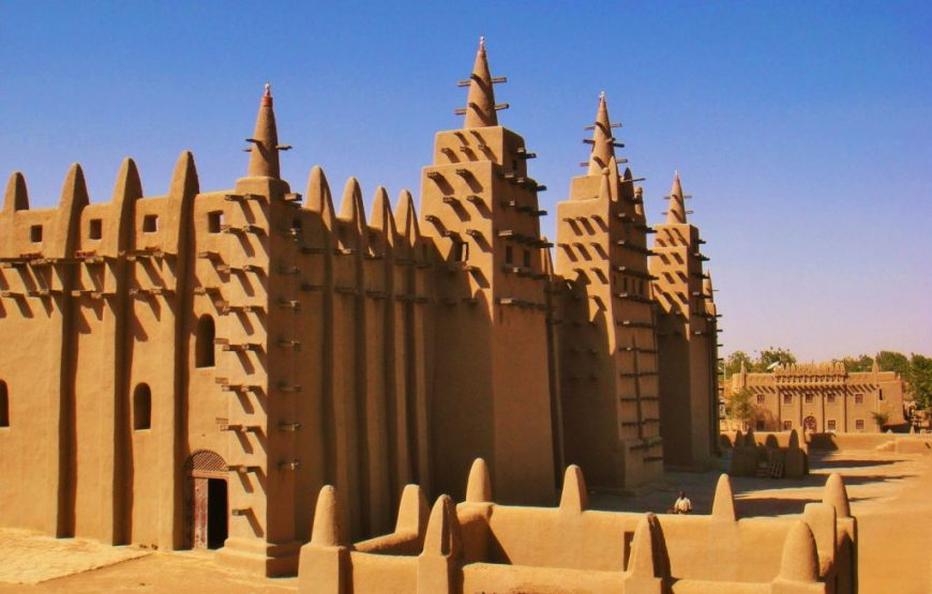

It is more productive to ask why the Mali Empire produced the architecture it did, rather than why it did not build more monumental structures. Mali’s known architectural achievements, such as the famed Djenné Mosque, already showcase the empire’s priorities.

Mansa Musa’s wealth, often exaggerated in popular accounts, has been re-evaluated by historians. He was undoubtedly wealthy, but not the absolute richest globally. His famous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 was a highly political act, planned over a decade. This journey projected power and wealth internationally but diverted attention and resources towards the pilgrimage rather than large-scale local building projects.

The Mali Empire’s wealth came primarily from gold and trade. Its economy functioned within a network linking West Africa to North Africa and beyond. Investments likely focused on maintaining these trade relationships, strengthening political alliances, and religious patronage rather than monumental architecture as seen in other empires.

Additionally, architectural styles and construction methods in West Africa utilized materials such as mudbrick, which do not preserve as extensively as stone. This preservation challenge means less evidence survives compared to other regions, affecting our understanding of the scale and scope of Mali’s architectural output.

Social and political structures in Mali probably emphasized different expressions of power, including oral traditions, administrative control, and religious influence, over architectural grandeur.

- The question “why didn’t Mali produce more monumental architecture?” is difficult due to the nature of historical evidence and counterfactual reasoning.

- Mansa Musa’s wealth was politically showcased during his hajj, possibly limiting local architectural investments.

- Economic and political priorities favored trade and influence over monumental building projects.

- Construction materials and preservation issues limit surviving examples of Mali’s architecture.

- Cultural expressions of power took forms other than monumental structures.

Why Didn’t the Mali Empire Under Mansa Musa Produce More Monumental Architecture?

Simply put, the Mali Empire under Mansa Musa didn’t build more monumental architecture because history, circumstances, and priorities of the time shaped a different kind of legacy — one that wasn’t focused primarily on grand stone monuments but on trade, culture, and diplomacy. Now, isn’t that a surprising answer? Let’s unpack why this fascinating empire, famous for its immense wealth and Mansa Musa’s legendary pilgrimage, didn’t flood the landscape with colossal buildings like some other great empires did.

First things first — asking “Why didn’t X do Y?” questions is a tricky business for historians. You’re essentially asking people of the past to explain why they didn’t predict the future. History doesn’t deal well with counterfactuals (what might have happened). We know a lot about what did happen, but much less about the roads not taken.

Instead of focusing on “Why didn’t they build gargantuan monuments?” it’s more rewarding to ask, “Why did they build what they actually built?” That’s a mindset shift like turning your telescope to look at stars that shine rather than at empty space. This way, we find that the Mali Empire focused on paths aligned with its own environment, culture, and political needs.

The Wealth of Mansa Musa: Not All That Glitters Is Gold (Or Is It?)

Let’s talk riches without the fairy-tale distortion. Mansa Musa is often crowned the “wealthiest man in history.” Spoiler alert — history offers a more nuanced story. Although Mali controlled vast gold mines and thrived in trans-Saharan trade, recent evaluations suggest that Musa might not have been the absolute richest individual alive at his time.

Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 grabbed global attention because of its scale and spectacle. He didn’t just stroll across the desert; he traveled with an enormous entourage, carrying so much gold that the price of gold in Cairo reportedly dropped for years!

But why spend so much gold publicly? Historians now see the journey as more than personal devotion — it was a calculated political show. This pilgrimage was a carefully planned act of statecraft, a way to introduce the Mali Empire to the wider Islamic world with grandeur and seriousness. Musa spent over a decade preparing, saving, and organizing this grand display of power and prestige.

Context Matters: Environment, Culture, and Urban Planning

So if wealth was abundant and political showmanship was a factor, why no towering pyramids or sprawling palaces? The Mali Empire existed in a different environmental and cultural context than, say, ancient Egypt or Rome.

Building monumental stone structures requires specific materials, technology, and sometimes the cultural will to invest massive resources in permanent buildings. The Sahelian environment limited the availability of stone and timber — essential components for grand architecture in other places.

Instead, Malians perfected the art of earthen architecture, using mudbrick and adobe. Famous examples like the Great Mosque of Djenné reflect this tradition. These structures aren’t skyscrapers to a stone-mason, but they’re architectural marvels adapted brilliantly to local climate and cultural practices.

Mali’s architectural achievements were beautiful, practical, and sustainable. They symbolize a civilization tuned in to its surroundings rather than obsessed with mere scale.

Trade, Diplomacy, and Education: Mali’s Real Monuments

Instead of monumental stones, Mali’s true monuments were its flourishing trade routes and centers of learning. Timbuktu, famously associated with Mansa Musa’s reign or soon after, became a beacon of Islamic scholarship. This intellectual capital arguably outweighs any physical monument in historical impact.

Eventually, the legacy of Mali stretches beyond bricks and mortar. The empire’s investment in scholarship, diplomacy, and trade infrastructure built enduring bridges that lasted centuries — arguably as monumental as any palace.

So, What Can We Learn?

This discussion reveals how asking perfectly framed historical questions matters. Instead of lamenting “Why didn’t the Mali Empire produce more monumental stone buildings?”, appreciating the empire on its terms reveals a rich tapestry of culture, environment, politics, and economy uniquely suited to its time and place.

Next time you hear about Mansa Musa, think beyond gold and grand construction. Picture a leader who understood power’s subtler expressions — pilgrimage as political theater, earthen mosques as cultural pride, and investing in people through education.

Did the Mali Empire run out of ideas for monuments, or did it redefine what ‘monumental’ meant in its world? I’d say the latter. How often do empires rewrite the rulebook on legacy?

Curious to Explore More?

- What other civilizations chose environment-friendly architecture over grandiose stone monuments?

- How did trade routes shape African empires in comparison to European or Asian counterparts?

- Could modern leaders learn something from Mansa Musa’s political showmanship and strategic investment in education?

These questions might lead you down intriguing paths of history, revealing that monumentality doesn’t always mean “bigger and taller.” Sometimes, it means “smarter, adaptable, and sustainable.” Now, doesn’t that change your view of history?

Why might it be difficult to determine why the Mali Empire under Mansa Musa did not produce more monumental architecture?

It is hard to prove what could have happened but didn’t. Historians rely mostly on records of actual events, not counterfactuals. Also, asking why something didn’t happen assumes past people saw options as we do now.

Could Mansa Musa’s pilgrimage have influenced the empire’s architectural choices?

His pilgrimage was a political act planned over many years. This planning might have directed resources and attention away from large building projects in the empire.

Was Mansa Musa truly the wealthiest man in the world, and how does that affect the question?

His wealth might have been overstated. If so, resources for monumental architecture may have been less available than popularly thought.

Why should the question be reframed when studying Mali’s historical architecture?

Asking why certain monumental projects happened is more effective than why they didn’t. It focuses on known actions and decisions, offering clearer historical insight.

Did the Mali Empire under Mansa Musa have other priorities besides monumental architecture?

The empire focused on trade, politics, and religion. These goals could have taken precedence over large-scale building projects.