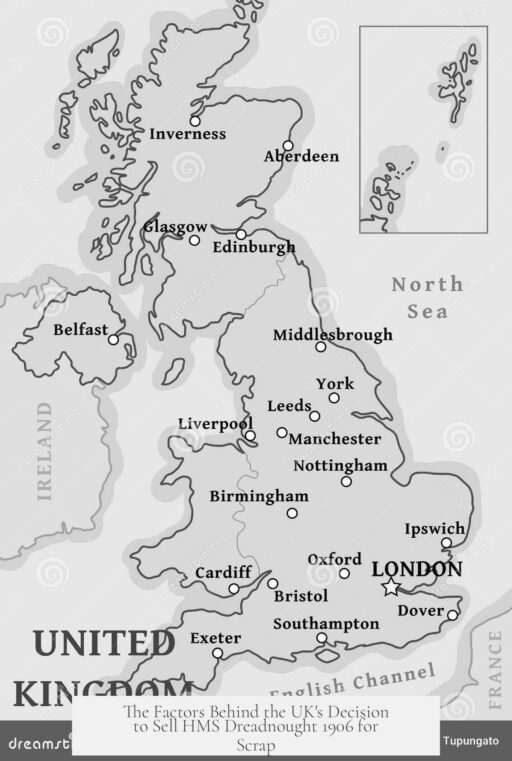

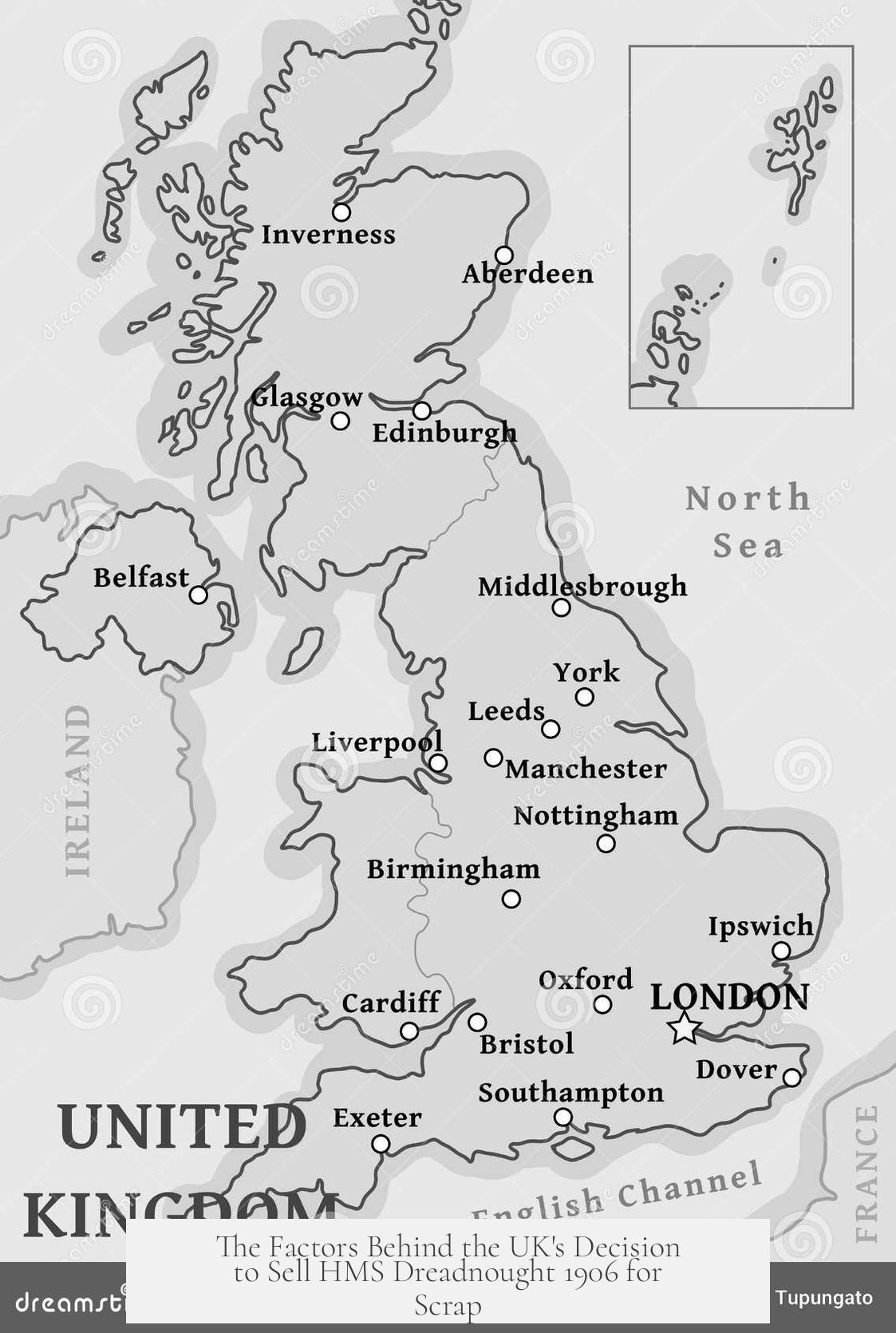

The UK sold HMS Dreadnought (1906) for scrap due to a combination of high maintenance costs, limited public interest in preserving ships without distinguished combat records, economic pressures following World War II, and international naval treaty obligations that identified obsolete battleships for disposal.

Despite HMS Dreadnought’s revolutionary design rendering all previous battleships obsolete, several factors influenced the decision to scrap her rather than preserve her as a museum ship or keep her in active service. These factors include economic realities, lack of profitability for museum vessels, and rapid naval modernization driving international arms control agreements.

HMS Dreadnought represented a breakthrough in naval technology when launched in 1906, introducing uniform big guns and steam turbine propulsion. However, she did not have a significant combat record during World War I, which made public interest in preserving her as a naval museum uncertain. Restoring and maintaining historic ships demands extensive financial resources. For context, the restoration of HMS Victory in 1922 cost about £160,000, equivalent to roughly £10 million today. Ongoing operating costs such as corrosion control, upkeep of machinery, and staffing add further expenses.

The British Admiralty and government were skeptical that Dreadnought would attract enough visitors to offset these costs. Victory was a famous warship with a storied history, yet still struggled financially. A ship like Dreadnought, despite its revolutionary design, lacked similar public appeal due to limited wartime fame. The prevailing view was that Dreadnought’s preservation as a museum ship would be financially unsustainable.

Economically, scrapping HMS Dreadnought provided significant financial returns. The British government operated the British Iron & Steel Corporation (Salvage) Ltd (BISCO) to manage raw material supplies essential for post-war industry recovery. Old naval vessels were handed over to BISCO, which contracted breakers’ yards to dismantle them and recycle the steel. Scrapping a battleship could yield £450,000 in 1945 pounds (about £20 million today), a vital revenue source for a war-ravaged nation rebuilding its economy and industry.

The scrapping effort not only generated income but reduced naval maintenance burdens. Keeping obsolete ships required crews and costly upkeep. Removing such vessels freed funds and personnel for more modern naval efforts. The scrapped steel also supported British heavy industry, accounting for about 3% of the national steel output annually.

Naval heritage preservation was not a widespread priority before the 1970s. HMS Victory was unique as a preserved Royal Navy ship during that period. Other historic vessels often served secondary roles or languished in non-frontline service for decades. For example, HMS Warrior served as a depot and oil jetty, while the monitor M33 functioned as a floating office and training platform after World War I. Old ships were often repurposed pragmatically rather than preserved for posterity. HMS Trincomalee was even sold for use as a sailing holiday camp.

Technological obsolescence further pushed the decision to scrap Dreadnought. Naval technology advanced rapidly in the early 20th century, making many ships outdated quickly. To manage arms races and reduce costs, major powers negotiated treaties limiting naval tonnage and capital ship numbers. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 specifically targeted outdated battleships like HMS Dreadnought for disposal. This treaty sought to cap naval armaments and required signatories to scrap or convert older capital ships.

This treaty had a direct impact on the fate of HMS Dreadnought. The need to adhere to international agreements and maintain a modern, competitive fleet reduced incentives to retain ships that no longer contributed strategically. Thus, even though Dreadnought was historically significant and technically advanced in her time, she was identified as surplus under treaty limits.

| Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| High Restoration & Maintenance Costs | Ships like Dreadnought required expensive restoration and ongoing upkeep, often exceeding potential museum revenue. |

| Lack of Visitor Interest | Dreadnought’s limited combat role reduced public appeal compared to more famous ships like HMS Victory. |

| Economic Benefit from Scrapping | Scrapping generated substantial funds and recycled steel vital for post-war British industry. |

| Limited Naval Heritage Preservation | Few ships were preserved before the 1970s; practical reuse or scrapping was more common. |

| Naval Treaties & Obsolescence | Washington Naval Treaty required disposal of obsolete capital ships including Dreadnought. |

These factors reflect the complex balance between historical significance, economic realities, and international diplomacy shaping the fate of HMS Dreadnought. Her scrapping underscores the challenges of preserving early 20th-century naval heritage amid rapid technological change and post-war recovery needs.

- High costs and uncertain museum profits deterred preservation.

- Scrapping provided much-needed funds and materials for British industry.

- Limited public interest in older ships without major wartime fame existed before the 1970s.

- Naval treaties enforced disposal of obsolete battleships, including Dreadnought.

- Rapid naval innovation rendered many early dreadnoughts strategically outdated.

Why was HMS Dreadnought scrapped despite its technological importance?

HMS Dreadnought was scrapped because it had little combat history and was unlikely to attract enough visitors to cover restoration and maintenance costs as a museum ship.

How did economic factors influence the decision to scrap HMS Dreadnought?

Scrapping HMS Dreadnought generated significant revenue and helped support the steel industry, which was vital for Britain’s post-war economic recovery.

Did naval treaties play a role in scrapping HMS Dreadnought?

Yes, naval treaties like the Washington Naval Treaty required the reduction of certain ship types, leading to the scrapping of ships like HMS Dreadnought to maintain naval balance and modernization.

Why was preserving old warships not a priority during HMS Dreadnought’s time?

Before the 1970s, there was little interest in preserving naval heritage, and old ships were often repurposed for non-museum roles or scrapped to save costs.

What role did the British Iron & Steel Corporation (BISCO) have in the scrapping process?

BISCO managed the transfer of surplus naval ships like HMS Dreadnought to breaker’s yards, ensuring valuable scrap metal was recycled for industry use.