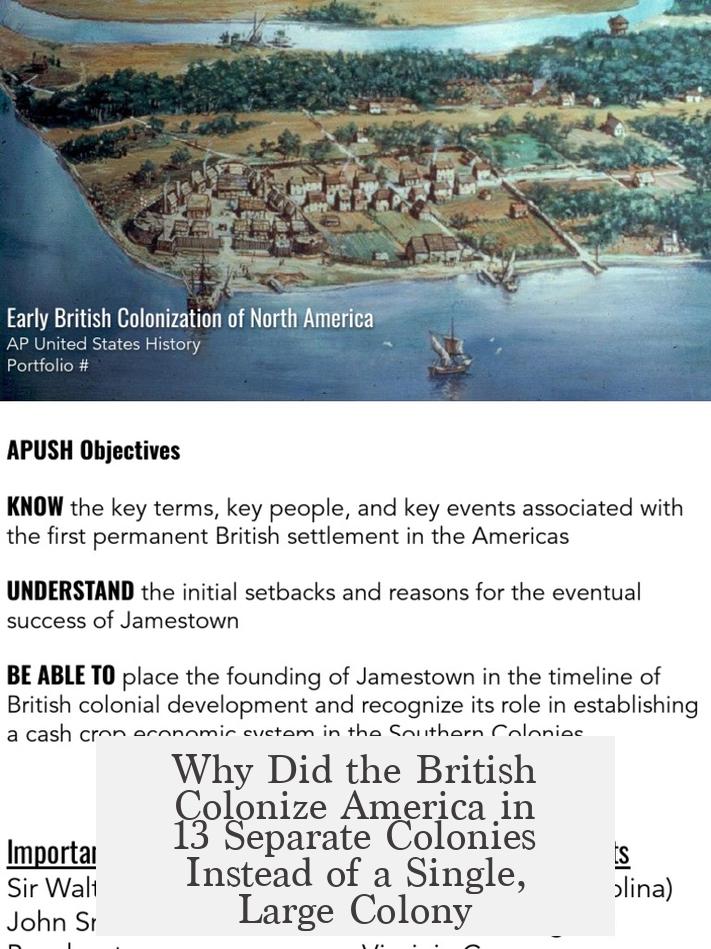

The British colonized America in 13 separate colonies instead of a single, large colony because these settlements were established by different groups at different times, under varied legal charters and economic motives. The vast geographic spread and administrative difficulties made a unified colony impractical. Each colony developed distinct identities, political structures, and purposes, reinforced by failed attempts at consolidation and the British colonial strategy of localized governance.

The thirteen colonies originated from independent efforts and charters granted by the British Crown. Early settlers arrived in disparate waves, often with specific goals and privileges. For instance, Virginia began in 1607 as an enterprise to mine gold but shifted focus to tobacco farming. Maryland, founded in 1632, granted special legal privileges akin to England’s County Durham and became a haven for Catholics. Pennsylvania, established in 1681, served as a refuge for Quakers and religious dissenters. These varied aims shaped distinct governance and social structures.

Geography played a significant role. The colonies stretched along the Atlantic coast, separated by large distances requiring weeks of travel by sea. Such distances complicated centralized administration. Coastal populations rarely moved far inland, resulting in communities that were self-reliant and locally governed. Managing these scattered colonies as a single entity posed logistical challenges that were nearly insurmountable during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

- Virginia, Maryland, and Pennsylvania each had unique charters specifying land rights and local governance.

- New England colonies—Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut—were founded by Puritans and dissenters with different religious and political ideals.

- New York, New Jersey, and Delaware emerged from lands seized from the Dutch, with separate administrative frameworks.

- Georgia was established in 1732 for English convicts and as a buffer against Spanish Florida, differing from northern colonies in purpose and population.

Legal foundations under different charters further reinforced separation. Each colony possessed distinct land patents, titles, and privileges. Virginia transitioned into a Crown Colony by 1624, while Rhode Island and Connecticut were born from Puritan dissenters opposing Massachusetts’ authoritarianism. Pennsylvania’s proprietary charter differed from royal colonies, granting William Penn extensive control to promote religious tolerance.

Attempts to unify the colonies under one government failed. The “Dominion of New England” (1686-1689), a royal initiative to consolidate control over Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, and New Jersey, collapsed within three years due to local resistance and administrative friction. This failure illustrated both the difficulties of managing diverse colonies under a single authority and colonists’ desire for self-governance.

Distinct identities arose because each colony developed independent legal systems, economic models, and social customs. Differences included variations in laws, privileges, trade advantages, and religious affiliations. Over time, these differences fostered unique political cultures. For example, Puritan New England had a strong communal, religiously-oriented governance model, whereas southern colonies like Virginia relied heavily on plantation agriculture and slave labor. These contrasts made political and administrative unity unattractive and complicated.

| Key Reason | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Varied Arrival Times and Groups | Settled by different people, each with distinct privileges and rights |

| Different Economic and Religious Goals | From tobacco farming to religious havens like Pennsylvania and Maryland |

| Geographic Spread | Colonies were miles apart, separated by sea and difficult land routes |

| Diverse Legal Charters | Separate land patents and rights created legal distinctions |

| Failed Consolidation Attempts | Dominion of New England collapsed due to resistance |

| Political and Social Identity Development | Each colony formed unique political customs, making unity difficult |

The British approach to colonization also relied on localized governance. Similar fragmentation occurred in other British territories such as Canada and South Africa. This pattern underscores why America developed as multiple distinct colonies rather than one large administrative unit. The Crown favored allowing local colonial governments to handle daily affairs, as long as overarching imperial interests were secured.

In summary, Britain’s colonization of America as thirteen separate colonies emerged from practical, legal, geographic, and political realities. Diverse founding motivations, long distances between settlements, incompatible charters, and developing unique social identities all worked against forming a single large colony. Moreover, failed earlier efforts at unification highlighted the impracticality of such consolidation during this era.

- Different groups arrived over decades, establishing separate colonies under distinct charters.

- Economic and religious objectives varied, affecting colony governance and society.

- Geographic distances made centralized administration difficult.

- Colonies developed unique political cultures and legal systems.

- The British preferred local control, allowing colonies to govern themselves within imperial bounds.

Why Did the British Colonize America in 13 Separate Colonies Instead of a Single, Large Colony?

The British established 13 separate colonies along the American Atlantic coast because distinct groups settled the land at different times, under unique charters with varied purposes, laws, and governance. Geographic distances and failed consolidation attempts reinforced this fragmentation, leading to independent political identities rather than one big unified colony.

You might wonder why, in the face of logistical convenience, Britain didn’t just create one massive colony stretching from New England down to Georgia instead of a patchwork. Let’s unpack the story, layer by layer, and discover why the British colonial approach was more like building blocks than one giant puzzle.

First, different groups of settlers arrived in America across several decades, each receiving separate charters or land patents from the English Crown. For example, Maryland’s charter borrowed from the legal model of County Durham in England. This diversity in origins meant each colony was its own little political experiment.

Moreover, consider the founding missions. Virginia, founded in 1607 at Jamestown, initially sought gold. That quest fizzled, until colonists pivoted to tobacco cultivation, which turned out to be the cash cow. Meanwhile, Maryland became a refuge for Catholics, with a tolerance policy quite progressive for the time. Pennsylvania was a safe haven for Quakers. Rhode Island welcomed religious dissenters escaping Puritan intolerance elsewhere. Different settlers, different religions, and different economic strategies – all demanding separate governance.

These colonies operated under various types of governance too. Some were proprietary colonies, like Maryland and Pennsylvania, run by individuals or families granted broad rights by the Crown. Others were Crown colonies, directly under royal administration—as Virginia was after 1624. North Carolina broke off from southern Virginia because settlers demanded local control, showing how even within regions, administrative borders adapted to local politics.

Here’s a fun fact: the British tried to merge some colonies. In 1686, they created the Dominion of New England, aiming to consolidate Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, and New Jersey. That experiment lasted only three years before collapsing under colonial resistance. Colonists didn’t want to lose their self-rule or their unique legal traditions; the attempt underscored how fiercely local identities had grown.

Another practical factor was geography. Traveling from Maine to Georgia by sea took weeks. Govern from London? That was nearly impossible with 17th-century communication. And on land, the Atlantic Coastal terrain was far from easy to traverse. This geographic spread favored localized administrations tuned to the immediate needs and challenges of their region.

Each colony had distinct economies too. While tobacco thrived in Virginia, sugar was king in Barbados, and Pennsylvania pursued diverse agriculture and religious freedoms. These economic differences made a one-size-fits-all government impractical.

And speaking of identities—over time the 13 colonies developed their own legal codes, trading privileges, and ecclesiastical relationships to the Church of England. These differences forged separate political cultures, which later fueled revolutionary spirit when the colonies sought independence.

| Key Reason | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Different groups at different times | Separate charters and privileges | Maryland’s charter modeled on County Durham |

| Varied founding purposes | Religious refuge, economic aims | Virginia’s tobacco, Pennsylvania for Quakers |

| Geographic separation | Difficult central administration | Weeks by sail between colonies |

| Legal foundations | Proprietary vs Crown colonies | Calvert family in Maryland, Crown colony Virginia |

| Failed consolidation attempts | Colonial resistance to loss of autonomy | The short-lived Dominion of New England |

| Distinct local identities | Unique laws, economies, church relations | Each colony operated differently |

| Localized British colonial strategy | Colonies served different needs | Patchwork across British Empire |

From Patchwork to Powerhouse: The Real American Experiment

The British Empire was more patchwork than blueprint when it came to colonization worldwide. Just look beyond the 13 colonies: Canada’s settlements of Nova Scotia, Quebec, and Newfoundland were separately governed. Almost every British colony, from South Africa to the Caribbean islands, developed independently with specific colonial charters designed for local circumstances.

Take South Africa, for instance—British Kaffraria, Griqualand West, and Basutoland started as separate colonies due to local governance needs. The lesson? Britain preferred tailored governance to one-size-fits-all control.

Back in America, this localized colonial approach created distinct political cultures essential to the country’s later unity and diversity. Each colony sharpened its own identity. They debated religious freedom, economic strategies, governance styles, and trade privileges. This laid the groundwork for the United States, a nation born from negotiated differences.

Have you ever thought about how this fragmentation influenced American politics today? The states still treasure their autonomy, reflecting colonial roots. The decentralized nature of the early colonies shaped a federal system that balances local and national power.

Why Didn’t Britain Force Unification Sooner?

Could the British Crown have forced the colonies into one entity earlier? Possibly, but why rock the boat when localized administrations worked well for tax revenue and maintaining control from afar? Colonists valued their charters as rights. A unified large colony would have been drastically harder to govern given the communication delays, distinct populations, and divergent local interests.

The failed Dominion of New England proved it: the colonies would resist centralization that diluted their privileges. These early lessons defined British colonial policy—to govern loosely but profit steadily. Trying to unify such diverse groups was like herding cats armed with legal charters and muskets.

Summary: A Story of Diverse Origins and Practical Governance

In essence, the thirteen colonies were separate because they started separately. Settlers came with different aims: seeking gold, religious refuge, political autonomy, or economic opportunity. The Crown granted charters reflecting these purposes. These settlements grew apart geographically and culturally, reinforced by failed centralization attempts and ongoing administrative challenges.

This mosaic of separate colonies was not a flaw but a calculated British strategy responding to realities on the ground. The colonies’ distinct identities and legal foundations created a vibrant political tapestry, setting the stage for a revolutionary era and, eventually, a nation built on both unity and diversity.

So, next time someone asks why America didn’t start as one big colony, you have the whole story: varied settlers, geography, charters, failed consolidation, and developing unique identities all combined to create the thirteen distinct colonies known in history—and, ultimately, the United States.

Isn’t it fascinating how these patchwork beginnings influenced the shape of American freedom and governance today? One giant colony might have been easier to manage on paper. But would it have created the dynamic, diverse nation we know? Probably not.