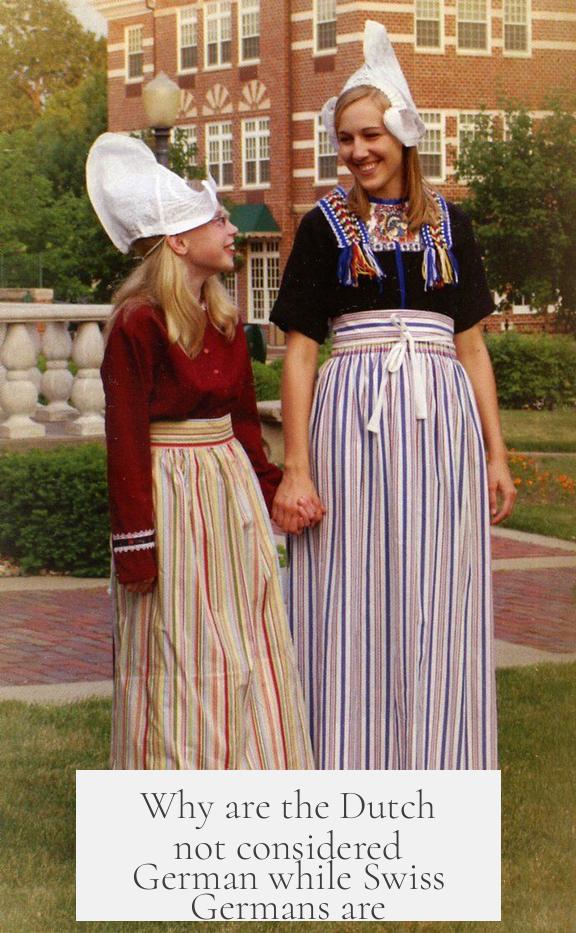

The Dutch are not considered German because they have a distinct standard language and a unique national identity that developed independently and earlier than modern German nationalism. Swiss Germans, despite speaking German dialects, are often seen as part of the broader German linguistic sphere due to their use of the same standard German language, yet they maintain a separate Swiss national identity shaped by Switzerland’s multilingual political landscape.

The separation between Dutch and Germans arises primarily from language standardization and national development. The Dutch language evolved under the influence of Bible translations like the 1548 Leuven and the 1618 States (Statenvertaling) versions, leading to a standardized Dutch used in governance and media in the Netherlands and Belgium. German dialects, including those spoken in Switzerland and Austria, use a common standard known as Schriftdeutsch or Hochdeutsch, originally shaped by Martin Luther’s Bible translation in 1522. This shared standard language ties together German-speaking peoples, including Swiss Germans who write and communicate in this version of German.

Swiss Germans speak dialects that differ considerably from standard German, but for formal purposes, they adopt the German written standard. By contrast, Dutch is a separate West Germanic language with unique grammatical features, phonology, and vocabulary. There is no single West-Germanic standard language uniting Dutch and German; instead, there are distinct Dutch and German standards. Swiss Germans, Austrians, and Germans share a standard language yet are recognized as separate national groups, while the Dutch use their own language and are a separate nation.

| Aspect | Dutch | Swiss Germans |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Language | Standard Dutch | Standard German (Hochdeutsch) |

| Language Family | West Germanic (distinct) | West Germanic (German dialects) |

| National Identity | Independent Dutch nation, early-modern development | Swiss national identity, multilingual state |

| Historical Statehood | Formed Dutch Republic post-Habsburg rule | Swiss Confederation, independent since medieval times |

The Dutch ethnicity and nationhood crystallized during the Dutch Revolt in the late 16th century, long before Germany became a unified state in 1871. Dutch nationalism and identity are deeply tied to their triumph over Habsburg Spain and their Golden Age in the 17th century, featuring robust commerce, arts, and religious freedom. This separate path created a strong civic identity, distinct from German ethnic nationalism that emerged later.

Swiss Germans, meanwhile, are part of a multilingual and federal nation that includes French, Italian, and Romansh speakers. Swiss identity centers around political institutions, neutrality, and direct democracy rather than ethnicity or a single language. The German spoken in Switzerland is a dialect continuum linked to German dialects but politically and nationally separate from Germany.

Ethnicity, language, and nationhood rarely align perfectly. The Dutch and Swiss show how linguistic closeness does not automatically translate into shared national or ethnic identity. Dutch and German dialects exist on a continuum, and linguistic differences are significant but gradational. The same dialect continuum is true for Germans and Swiss Germans, who nonetheless are united by a common written language. The Dutch, using a distinct standard, stand apart linguistically.

19th-century German nationalism sought to incorporate diverse German-speaking populations like the Dutch and Swiss Germans into a broader German Volk. This was more ideological myth-making than historical or national reality. The Dutch resisted absorption with a strong separate identity, shaped by early independence and cultural achievements.

The transfer of the Netherlands to the Spanish Habsburgs by Charles V and the subsequent Dutch Revolt further solidified Dutch separateness. Meanwhile, Swiss confederation and autonomy maintained through time preserved a distinct national identity transcending linguistic ties.

- Dutch are separate from Germans due to unique language and early nationhood.

- Swiss Germans share a standard German language but have their own Swiss identity.

- Language standardization affects national identity and perception.

- Ethnic identity does not always correspond with linguistic similarity.

- Historical developments shaped distinct Dutch and Swiss national identities before German unification.

- 19th-century German nationalism tried to unify German-speaking peoples but met resistance from Dutch and Swiss.

Why are the Dutch not considered German while Swiss Germans are?

The simple answer: The Dutch use the Dutch standard language, while Swiss Germans write and speak a standard German variety. Sounds straightforward, right? But peel back the layers and you find a fascinating story of language, history, identity, and politics that explains why these groups, though linguistically related, belong to different national categories.

Language, Borders, and Standards: The Twilight Zone of Dialects

First off, borders and languages are slippery. They change and evolve constantly. What is “fixed” in one century can be fluid in another. And that applies both to where countries end and begin, and to how languages and dialects stretch and morph across territories.

Almost every language on Earth is part of some dialect continuum, a fancy term meaning that speech changes gradually across regions instead of popping into sudden, distinct languages. So, if you start in one village and travel down the road, the accent shifts just slightly every mile. Before you know it, folks are speaking what we’d call a different dialect or even a separate language.

Within this West-Germanic dialect continuum, we find Dutch, German, Swiss German, and Austrian German nestled cheek by jowl. Yet, the Dutch have their own official standard language. The Germans and Swiss Germans share another. This standardization is key to understanding the distinction.

Swiss Germans and the Power of Schriftdeutsch

Swiss Germans speak dialects that sound very different from the High German spoken in Germany, but when it comes to official contexts, writing, media, and formal speech, they use Schriftdeutsch or Hochdeutsch (Standard German). This was shaped historically by cultural milestones like Martin Luther’s 1522 Bible translation, which helped form a middle ground standardized language used across German-speaking countries—including Germany, Austria, and Switzerland.

This common standard language binds these groups linguistically, despite their strong local dialects and identities.

The Dutch Language: A Separate Standard Emerges

The Dutch standard language also arose during the Reformation period but evolved distinctly from German. Influential translations, like the 1548 Leuven and especially the 1618 Statenvertaling, became the textual backbone for the Dutch language that the young Dutch state adopted after shaking off Spanish Habsburg rule in 1648.

Unlike Swiss Germans, the Dutch never adopted the German standard language but instead nurtured their own linguistic identity. Their language isn’t just a dialect of German; it has unique grammatical and phonological traits—such as differences in case use, pronouns, and vowel changes—that set it apart. Even when dialects form a continuum, the Dutch held onto their distinctive language features and developed it as a national symbol.

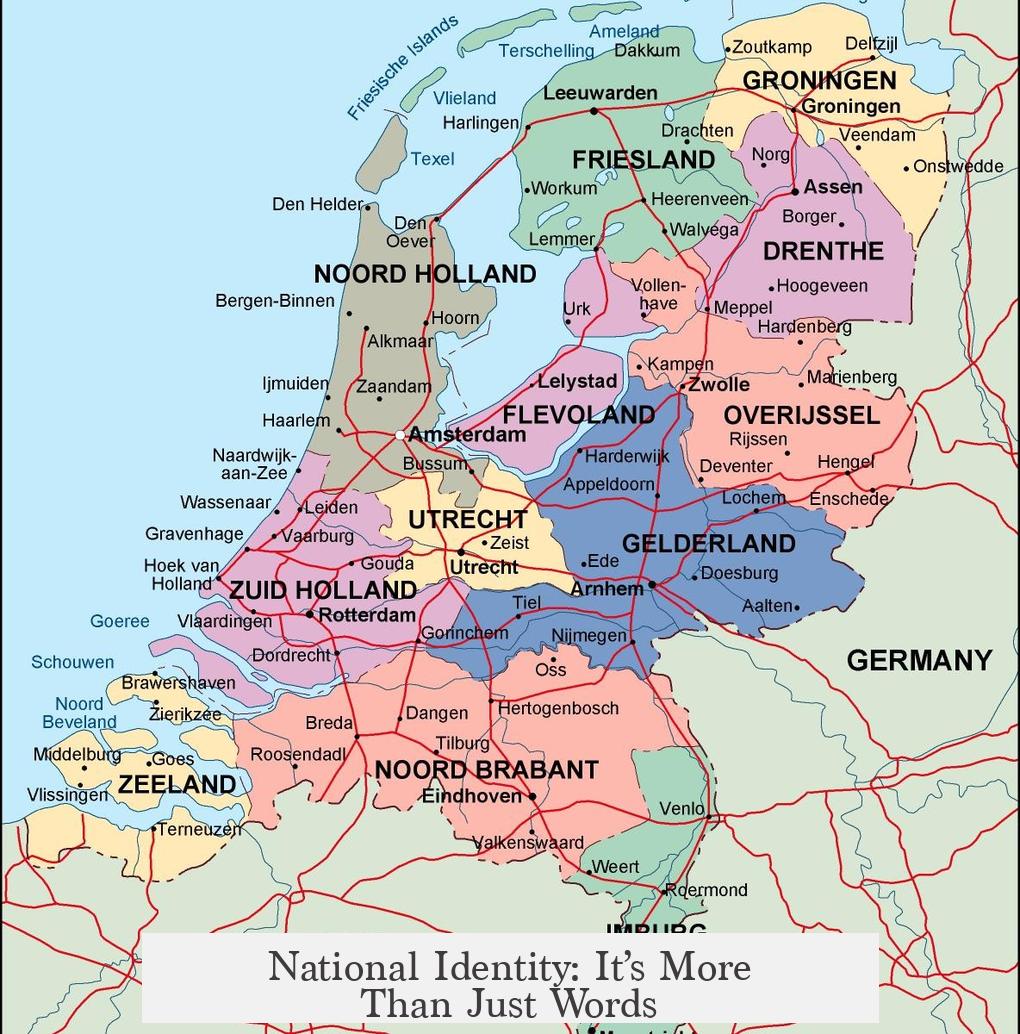

National Identity: It’s More Than Just Words

Sure, language plays a huge role, but identity is a messy cocktail of history, politics, and culture. The Dutch don’t see themselves as Germans because they didn’t grow up as part of a German nation-state. In fact, the Dutch nation formed earlier than the German one. Long before the German Empire was declared in 1871, the Dutch had already cemented their distinct national identity, largely through their hard-fought independence from the Habsburgs in the late 16th century.

The Dutch Revolt wasn’t just a war; it was a defining moment infusing Dutch people with fierce pride in liberty and independence, carving out their image as a unique “new world” nation. This identity blossomed during the remarkable Dutch Golden Age, when the republic dazzled Europe and beyond with its commerce, technology, and cultural achievements. At this peak, the Dutch didn’t need to borrow a German identity—they were clearly their own nation.

So, the Dutch are not “offshoots” of a greater German ethnicity but a nation shaped by its own distinct historical journey. The idea that Dutch are just “lost German tribes” is largely a 19th-century German nationalist invention attempting to fold many neighboring ethnic groups into the German fold. Dutch folks happily shrugged off this notion.

Switzerland: A Multilingual Puzzle with a Civic Identity

The Swiss situation is more nuanced. Switzerland is a multilingual country with German, French, Italian, and Romansh speakers. The German-speaking Swiss indeed speak dialects related to German dialects, and culturally, they share many traits with Germans. But even then, Swiss German speakers do not consider themselves “German” in a national or ethnic sense.

Switzerland proudly maintained its independence during the rise of 19th-century German nationalism. Instead of melting into the German national identity, the Swiss forged a civic identity focused on shared political institutions like direct democracy, a commitment to neutrality, and a unique confederation heritage. This Swiss model of nationhood transcends linguistic and ethnic differences and defines them through collective governance rather than blood or tongue alone.

Language Doesn’t Equal Ethnicity or Nationality

We often hear people say “language defines a people.” But the reality is trickier. Dialects and languages don’t neatly map to ethnic or national identities. We can find regions where dialects spread across different countries with different national self-images.

Look elsewhere in Europe. French and Italian languages come from related Romance roots but belong to distinct ethnic groups and nations. Russian and Ukrainian dialects straddle a linguistic borderline but draw strong ethnic distinctions. Finnish and Estonian share a linguistic family but are culturally separate. This is normal. Shared or similar language doesn’t guarantee a shared sense of nationhood.

The Dutch and Germans fit this pattern well. Although their dialects interlock within a continuum, ethnic identity breaks where politics and history draw lines.

What About the 19th-Century Nationalism Factor?

In the 1800s, the idea of the nation-state took firm root in Europe. Nationalists sought to thread together historical, linguistic, and cultural patches into one larger tapestry. German nationalists especially tried to claim various regional groups—including the Dutch and Swiss—as part of an overarching German Volk (folk or people).

This nationalist myth-making explains why the Dutch were sometimes seen as Germans in the past. Yet, reality didn’t always agree. The Dutch had long established their own national story, centered on independence, a golden age, and political institutions. The Swiss, likewise, resisted incorporation into any pan-German identity by promoting their own unique political unity and diversity.

Historical Splits: Charles V and the Netherlands

History also pushed the Dutch and Swiss into separate orbits. Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, controlled a vast empire that included the Low Countries (today’s Netherlands and Belgium) and parts of modern Germany. Upon retirement, he split his empire between his son, who got Spain and the Netherlands, and his brother, who got Austria.

This transfer under the Spanish Habsburgs set the stage for the Dutch revolt, while Switzerland’s relationship with the Holy Roman Empire was distinct, more confederated and less centralized. The Northern Netherlands eventually became an independent state—the Dutch Republic—founding an identity that was truly their own.

Summing It Up: What Really Makes the Difference?

- Language Standardization: Swiss Germans use Schriftdeutsch, the standard German language shared across Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. The Dutch use their own distinct Dutch standard language.

- Historical Nation Formation: The Dutch nation formed earlier and quite independently of Germany, with battles for independence shaping distinct identity. Swiss identity revolves around civic nationalism, shared institutions, and multilingualism.

- Ethnic vs. Linguistic Identity: Sharing language doesn’t mean sharing ethnicity or nationality. Dialect continua blur lines, but history and politics draw real boundaries.

In short, The Dutch are not considered German because their language, history, and political development forged a unique national identity separate from the German one, while Swiss Germans share Germany’s standard language and cultural traits yet emphasize a distinct Swiss identity rooted in political and civic institutions, transcending ethnic-linguistic boundaries.

So, Why Should You Care?

Understanding this explains so much about European geography, history, and identity politics. It teaches us that language alone cannot predict identity. It’s a powerful reminder that nations are living stories, crafted not just from shared speech but from shared experiences, political struggles, and choices.

If you ever find yourself lost in translation between Dutch, German, or Swiss German speakers, remember: it’s not just about the words. It’s about history, pride, and the unique paths people have chosen. And yes, sometimes a language is “a dialect with an army and a navy,” but that’s just the beginning of the tale.

Final Thought: A Linguistic-Political Dance

Language is only one dancer on the stage of national identity. Politics, history, and culture join in a complex choreography. The Dutch and German-speaking Swiss are perfect examples. Both speak close relatives in the West-Germanic family but dance to different tunes when it comes to who they are.

In the end, the Dutch are masters of carving out a distinct voice and nation against the odds. The Swiss are maestros in orchestrating unity within diversity. And Germany? Well, it’s a central player in both stories but never the sole director.

Which brings us back to a curious question: If languages mix and merge so easily, why do people cling so fiercely to their national stories? Perhaps because those stories give shape to who they are, making the fuzzy borders on maps feel wonderfully real.