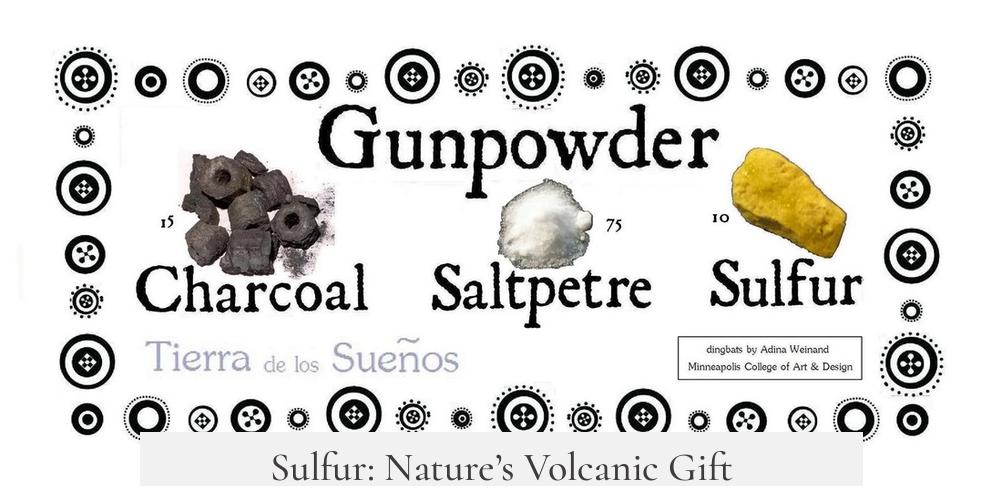

The original raw materials for gunpowder, or black powder, primarily saltpeter (potassium nitrate), sulfur, and charcoal, came from diverse natural and artificial sources across different regions, shaped strongly by geographic availability and historical trade networks.

Saltpeter is the key oxidizer in gunpowder. Its natural deposits, mainly in tropical climates, were limited in medieval Europe, demanding innovative methods and trade to meet rising military demand. European availability of saltpeter was scarce, requiring either local production or importation from abroad as firearm use grew in the late Middle Ages.

Europeans developed a process known as saltpeter beds or niter beds in the 16th century. Workers created compost heaps layering clay, urine, lime, straw, and dried plants, which after aging produced nitrates. Extracting saltpeter from these heaps involved digging and boiling the material to crystallize potassium nitrate. Urine and animal waste provided essential nitrogen sources.

Additionally, naturally nitrated soils could be found under floors or walls of privies and livestock barns due to accumulations of human and animal excrement. Saltpeter men sometimes harvested these soils, often without landowner permission, to secure supply, a practice that was both essential and unpopular in 17th-century England.

European saltpeter sources also included importation from natural deposits in India and North Africa, particularly Morocco, starting in the late 16th and 17th centuries. The demand and supply for saltpeter contributed to early global trade dynamics, with saltpeter becoming a valuable commodity linking Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Sulfur, the second key component, was more regionally available but still required trade and refinement. It often came from volcanic areas. Europe’s sulfur sources included the Aeolian Islands, Mt. Etna, and Pozzuoli in Italy, as mentioned in the 16th-century treatise Pirotechnia by Vannoccio Biringuccio. Iceland also exported sulfur during the later Middle Ages via Norwegian trading routes. Sulfur required melting and refinement, sometimes done at ports or arsenals, such as the royal refinement house in Copenhagen in the 16th and 17th centuries.

In Eastern Eurasia, sulfur trade was significant. Song Dynasty China, an early user of gunpowder weapons and fireworks, imported sulfur widely due to limited domestic volcanic sources. Trade routes connected sulfur sources across the Middle East, Korea, and Japan. Notably, Persian brimstone (sulfur) was transported to China as recorded by Persian poet Saadi Shirazi, highlighting its value in Eurasian commerce.

The trade routes for sulfur evolved from a China-centered system in the 13th century to a more complex, multipolar network by the 14th to 16th centuries, reflecting the spread of gunpowder weaponry across Asia during the so-called “Gunpowder Age.”

Japan’s case presents a contrast. While rich in volcanic sulfur, the country suffered from a shortage of saltpeter, delaying widespread adoption of gunpowder weapons until European contact. Japan imported most of its saltpeter during the Sengoku period from Southeast Asia and the Philippines. Export bans and harsh punishments in China to restrict saltpeter trade aimed partly to hinder Japanese access.

Despite bans, smuggling and official trade continued. In 1612, reports noted saltpeter prices in Japan were twenty times higher than in China, reflecting intense demand. Tokugawa Ieyasu actively requested guns and saltpeter imports from Siam in the early 17th century, underscoring the critical need.

Japan also pursued domestic production of saltpeter. Villagers created compost pits under house floors, layering organic materials like millet shells, hemp farm dirt, and silkworm waste—a method recorded in the mid-19th century. Through repeated yearly cycles lasting several years, this soil generated saltpeter extracted by rinsing and boiling. Early 17th-century records show that mountain villages supplied hundreds of kilograms annually, with increasing quotas over time.

By the mid-19th century, as military demands rose, Japan adopted European-style niter beds to scale production. These processes, taking up to two years, reflected the growing industrial approach to key raw material production in line with modern warfare needs.

| Raw Material | Primary Sources | Production/Extraction Methods | Regions Noted |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saltpeter (Potassium Nitrate) | Natural deposits (tropics), nitrated soils, compost heaps, import | Compost aging (niter beds), soil extraction, boiling for crystallization | India, North Africa (Morocco), Europe (local production), Japan (domestic and imports) |

| Sulfur | Volcanic deposits, trade | Mining volcanic sulfur, melting and refinement | Aeolian Islands, Mt. Etna, Pozzuoli, Iceland (via Norway), Middle East, Japan, Korea |

| Charcoal | Wood fuel (not detailed in sources) | Charring wood | Widely available globally |

The original raw materials for black powder shaped much early military technology and trade. Scarcity of saltpeter in Europe led to innovative local production methods and the development of global trade networks linking tropical deposits and Asian markets. Sulfur’s volcanic origins confined supply to specific areas, creating valuable trade goods and refineries. Japan’s reliance on imports and gradual domestic solution highlights the global interconnection in raw materials trade during the gunpowder era.

- Saltpeter, the oxidizer, naturally scarce in Europe, was produced locally or imported mainly from India and North Africa.

- Sulfur came from volcanic regions in southern Europe, Iceland, and Asia, requiring melting and refining before use.

- Japan had abundant sulfur but faced a saltpeter shortage, heavily relying on imports and limited domestic production.

- Saltpeter production involved compost-like niter beds exploiting organic nitrogen sources in soil and waste.

- Trade in gunpowder materials contributed to complex early global commerce across Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Where Did the Original Raw Materials for Gunpowder (Black Powder) Come From?

Let’s get straight to the point: The original raw materials for gunpowder—saltpeter, sulfur, and charcoal—came from diverse and often challenging sources, requiring clever production and extensive trade networks across continents. While this combo seems simple today, sourcing these ingredients centuries ago was a complicated, resourceful, and sometimes downright smelly affair. Curious how Europe, Asia, and beyond mastered this? Let’s dive in.

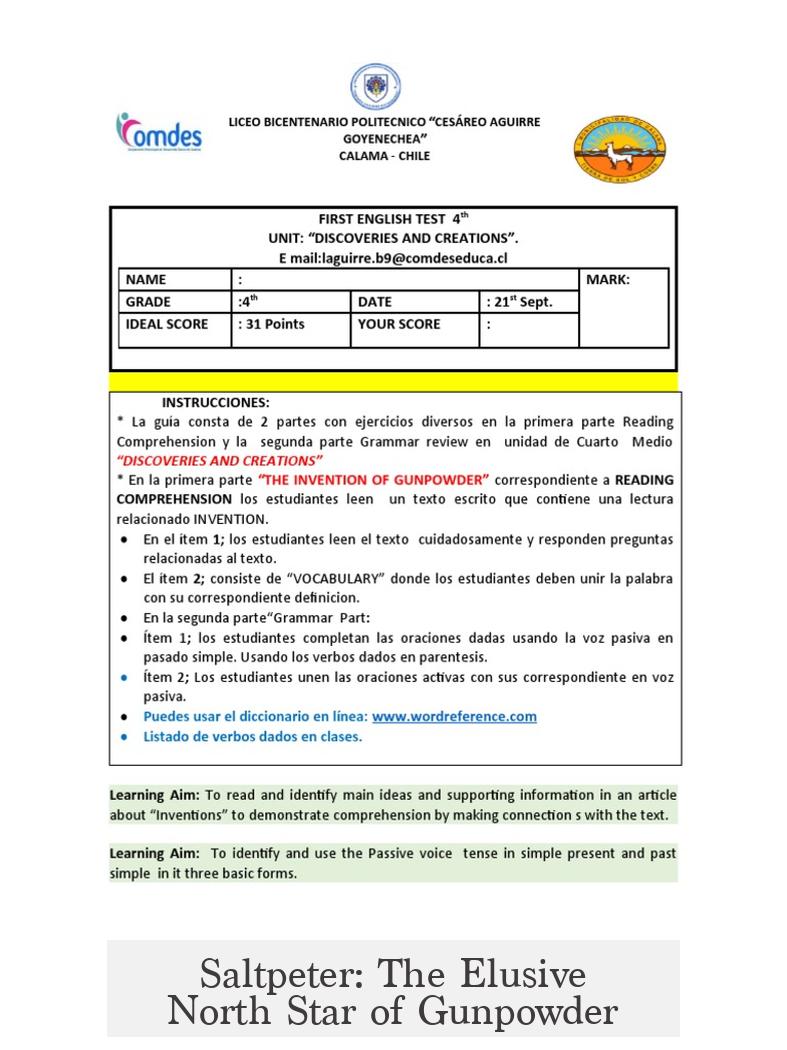

Saltpeter: The Elusive North Star of Gunpowder

Among the trio of gunpowder ingredients, saltpeter (potassium nitrate) was the trickiest to obtain. It’s the oxidizer that makes the magic happen. In Europe, saltpeter wasn’t just lying around waiting to be picked up. While the Earth contains natural deposits, especially in tropical areas, Europe had only scarce sources.

So what did they do when gunpowder demand exploded at the end of the Middle Ages? Europeans had to become innovative. They invented a way to manufacture saltpeter rather than waiting for nature to deliver it. Enter the saltpeter beds or “niter beds.”

These beds were essentially compost heaps built by layering materials like soil, clay, urine, lime, straw, and dried plants. Over time, bacteria in this mix converted nitrogenous waste into nitrates. Workers would dig up these aged piles, boil them, then crystallize saltpeter. Yes, urine and dung were part of the recipe—confirming that sometimes, science does involve a bit of the gross.

Imagine the saltpeter-man’s job in 17th century England—digging up nitrated soil from hidden nooks like barn floors and toilets. No wonder they were unpopular! These workers often risked landowner wrath, since they sometimes excavated without permission.

When home production wasn’t enough, England looked east. By the 17th century, massive saltpeter imports came from India, a country abundant with natural deposits. Smaller shipments also arrived from Morocco and North Africa.

Discussing saltpeter trade is like untangling one of the first global supply chains, long before Amazon. Demand dictated supply routes, political decisions, and even occupations…like the regrettably named “saltpeter-men.” Think of them as early supply-chain disruptors.

Sulfur: Nature’s Volcanic Gift

Unlike saltpeter, sulfur was easier to source, but not everywhere. Its main European homes were volcanic zones where this mineral occurs in “mountains,” not veins. Think: the Aeolian Islands near Sicily, Mount Etna, and Pozzuoli—yes, famous for spas and spicy eruptions alike.

A famous early European pyrotechnics manual from 1540, Pirotechnia, mentions these places as sulfur gold mines. Curious that sulfur was both natural and, compared to saltpeter, simpler to refine. Most refining involved melting sulfur in pits or melting houses near ports. For example, Copenhagen had a “sulfur house” in the 16th and 17th centuries just for this.

Outside Europe, Icelanders played a surprising role. In the Late Middle Ages, Iceland’s sulfur exports sent goods through Norway to European markets. These exports were important enough to warrant church intervention in 1279, preserving trading privileges for Icelandic sulfur.

East Asia’s Complex Sulfur and Saltpeter Story

The East brings complexity. Song China was a pioneering gunpowder power (960–1279 AD), using firearms and fireworks alike. However, sulfur was scarce within much of China. This shortage pushed China to import sulfur from afar—volcanic regions in southern Japan and Korea, and even Persia.

A Persian poet from the 13th century, Saadi Shirazi, mentions sulfur caravan routes reaching China, loaded on camel trains. It’s poetic proof that sulfur was a sought-after commodity linking Persia to the Far East.

By the 14th to 16th centuries, trade networks became multi-polar, centered on China and the Mongol empire initially, with the spread of gunpowder weapons amplifying demand everywhere in Eurasia. Intercontinental trade flourished as Asian and European powers sought enough raw materials to make their war machines go boom.

Japan’s Saltpeter Crisis: Import Reliance and Domestic Innovation

Japan, a volcanic land rich in sulfur, paradoxically lacked saltpeter. This shortage likely delayed the country’s widespread adoption of firearms until Europeans introduced them in the 16th century.

To feed their military’s growing saltpeter hunger, Japan relied heavily on imports. Apart from smuggling and trade, many shipments came from Southeast Asia and the Philippines, even under harsh export bans from China. Notably, by 1612, saltpeter prices in Japan soared to twenty times those in China—a staggering markup surpassing even silk and porcelain.

Tokugawa Ieyasu, the shrewd warlord, personally requested saltpeter and guns from Siam in multiple years (1606, 1608, 1610), revealing how critical foreign supply was.

Japanese Homegrown Saltpeter Production: A Long, Patient Process

Japan wasn’t content to rely solely on imports. From the late Sengoku period onward, efforts to produce saltpeter domestically took off.

One traditional Japanese technique involved digging pits near hearths, layering the soil with millet shells, hemp farm dirt, silkworm droppings, and dried leaves like mugwort. Seasons passed, and the soil was periodically dug up, mixed with fresh silkworm poo, and compacted again. After six years of this patient composting, saltpeter could be extracted by rinsing the soil and boiling the solution.

Initial production yielded hundreds of kilograms—enough for domains to tax villagers in saltpeter rather than rice. By the early 19th century, production reached 10 tons, a testament to the method’s effectiveness. Still, as Japan stepped into modern warfare, domestic supply couldn’t fully meet demand.

In 1855, the Kaga domain escalated efforts by purchasing nitrate-rich soil beneath old homes en masse and adopting European-style niter beds. Japanese production methods evolved as they studied foreign techniques, matching European efficiency just in time for the arms race of the late Edo period.

Bringing It All Together: A Global Story of Ingredients, Ingenuity, and Trade

What ties saltpeter, sulfur, and the charcoal story? The early gunpowder trade spun a vast, complex web of resource scarcity, innovation, and cross-continent exchange.

- Europe needed to manufacture saltpeter using compost piles due to poor natural deposits.

- Volcanic sulfur mines in southern Europe and Iceland provided ample sulfur.

- Asia, especially China and Japan, faced sulfur and saltpeter shortages differently; China imported sulfur, Japan grappled with saltpeter scarcity.

- International trade routes carried bulky, smelly, but vital goods from India, Persia, Southeast Asia, and beyond.

- Political tensions, bans, and smuggling all shaped the saltpeter trade—imagine regulation enforcement on a cargo of “powder stuff” in the 1500s!

So the “original” raw materials for gunpowder didn’t just appear magically. They required ecosystems of workers, traders, chemists, smelters, and politicians. From ancient compost piles layered with urine and dung, to volcanic landscapes rich in sulfur, to high seas routes trading camel loads of brimstone, this resource story is as explosive as the powder itself.

Why Does This Matter Today?

Understanding the origin of gunpowder’s raw materials gives us a fresh lens on history. It explains how technologies spread unevenly, shaped empires, and fostered early globalization.

It also reminds us that materials fundamental to conflict and development come from highly specific environmental and social contexts. Behind every invention is a network of supply challenges and inventive solutions—a lesson still relevant in tech, manufacturing, and trade today.

Next time you read about gunpowder—the “black powder” that rocked the medieval world—remember it was not just the spark but the earth, sweat, and smelly compost heaps that made it possible. Now, that’s a smokin’ mix of science and history.

Curious about how these raw materials were refined into the deadly powder and curious about charcoal’s role? Or want to hear tales of saltpeter smugglers stretching across continents? Stay tuned or comment below—because the story of black powder is as rich and gritty as its ingredients.