The point of the Vietnam War was to prevent the spread of communism in Southeast Asia while supporting the South Vietnamese government against the communist North. For the United States, it was a Cold War struggle aimed at containing Marxist-Leninist expansion. For the Vietnamese, it was a fight to end foreign domination and reunify their country.

The war’s core objective varied significantly between the Vietnamese and the Americans. From the Vietnamese viewpoint, the war was a continuation of their long struggle against foreign rulers, which included French colonialists and Japanese occupiers during World War II. They sought to end all foreign control, including the new presence of the United States. North Vietnam and the Viet Minh regarded themselves as the legitimate government of a unified Vietnam, aiming to abolish the artificial division created by the Geneva Agreement in 1954.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government framed the conflict as a necessary stand against communism, guided largely by the Domino Theory. This theory posited that the fall of one Southeast Asian country to communism would trigger a cascade of neighboring nations falling under communist control, threatening global stability. Following the 1949 communist takeover of China, American policymakers feared that countries like India and Indonesia would soon follow, which they regarded as a global catastrophe.

The United States’ direct involvement began in the 1950s with military advisors and escalated to large-scale combat deployments by 1965. The main U.S. military strategy focused on defending South Vietnam to enable it to stand independently against the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong. The U.S. operated mostly within South Vietnam and across the borders in Cambodia and Laos, attempting to disrupt communist supply routes and military activity.

The broader Cold War context underscored the conflict. It was not merely a local civil war but part of a global contest between the U.S. and its allies versus the Soviet Union and China. Both superpowers sought influence by supporting aligned governments. For communist states like the USSR and China, supporting North Vietnam was a way to expand Marxist-Leninist ideology and maintain regional influence, especially near China’s borders. For the U.S. and its allies—including Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, Thailand, and the Philippines—the goal was to contain that spread through the policy of containment, preventing further expansion beyond existing communist borders.

| Stakeholder | Primary Objective |

|---|---|

| North Vietnam & Viet Minh | End foreign domination, reunify Vietnam under communist rule |

| South Vietnam | Maintain independence (though government was widely seen as a dictatorship) |

| United States | Prevent spread of communism in Southeast Asia, uphold Domino Theory |

| US Allies | Support anti-communist efforts, fulfill treaty obligations |

| USSR & China | Expand communist influence, counter US in region |

Despite extensive U.S. efforts, the South Vietnamese government proved unable to defend itself economically, militarily, and politically. This insufficiency led to a gradual withdrawal of U.S. funding and troops, culminating in the final communist victory in 1975. The capture of Saigon marked the end of South Vietnam’s government and the reunification of the country under communist control.

The Domino Theory did not fully materialize as feared. Laos and Cambodia also fell to communism but large populous countries like India and Indonesia did not. Some argue the U.S. involvement delayed communist expansion, allowing Southeast Asian nations to develop stronger defenses. Nonetheless, the war is often viewed as a U.S. strategic failure since it did not accomplish its main goals.

Military strategy played a role beyond ideology or containment. The U.S. Navy identified controlling the Straits of Malacca as crucial for Pacific operations. Preventing communist control in northern Southeast Asia was necessary to maintain naval operational capacity without needing additional fleets, strengthening the rationale for intervention in Vietnam.

“The U.S. fought to stop the spread of communism and defend South Vietnam, but Vietnam aimed to reunify and free itself from foreign control. The conflict was a Cold War proxy battle with multiple layers of motives.”

- Vietnamese saw the war as a continuation of their anti-colonial struggle and national reunification effort.

- The U.S. aimed to contain communism and prevent a domino effect across Southeast Asia.

- Cold War rivalry between the U.S., USSR, and China shaped the strategic goals of the war.

- South Vietnam failed to sustain its sovereignty, leading to U.S. withdrawal and communist victory.

- Despite the defeat, some argue U.S. delay of communist control bought time for other nations.

- Control of key strategic points like the Straits of Malacca influenced U.S. military planning.

What Was the Point of the Vietnam War?

At its core, the point of the Vietnam War was a complex interplay between Vietnamese aspirations for independence and global Cold War politics centered on preventing the spread of communism. This conflict wasn’t just about two sides slugging it out with guns and bombs. It involved deep political beliefs, clashing ideologies, and the hopes of millions yearning for a voice.

So, let’s unpack this tangled historical knot, starting with the Vietnamese perspective. What did they want? How did global powers get involved? And how did the war’s outcome ripple across the world?

The Vietnamese Perspective: Fighting Foreign Dominance

The Vietnamese people had been through a rollercoaster of foreign rule. First, the French colonists called the shots, then the Japanese dropped by during World War II, only for the French to try reclaiming their spot afterward. Imagine trying to hold a party and having party crashers keep barging in. The locals just wanted their home back.

The Vietnamese fought to end this foreign dominance. After ousting the French again, they faced a new challenge — the Americans. But South Vietnam, propped up by the U.S., wasn’t the democratic oasis portrayed in American propaganda. Instead, it was a brutal dictatorship that people saw as yet another oppressive regime.

This pushed many Vietnamese to lean towards the communists, who offered arms, supplies, and technical support. Communist leaders like Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh considered themselves the legitimate government, aiming to reunify Vietnam after the country was split by the Geneva Agreement following the First Indochina War.

Once the U.S. left in 1975, Vietnam’s ties to communism cooled surprisingly quickly, showing that the war’s ideological battles were more flexible and pragmatic than rigid doctrines might suggest.

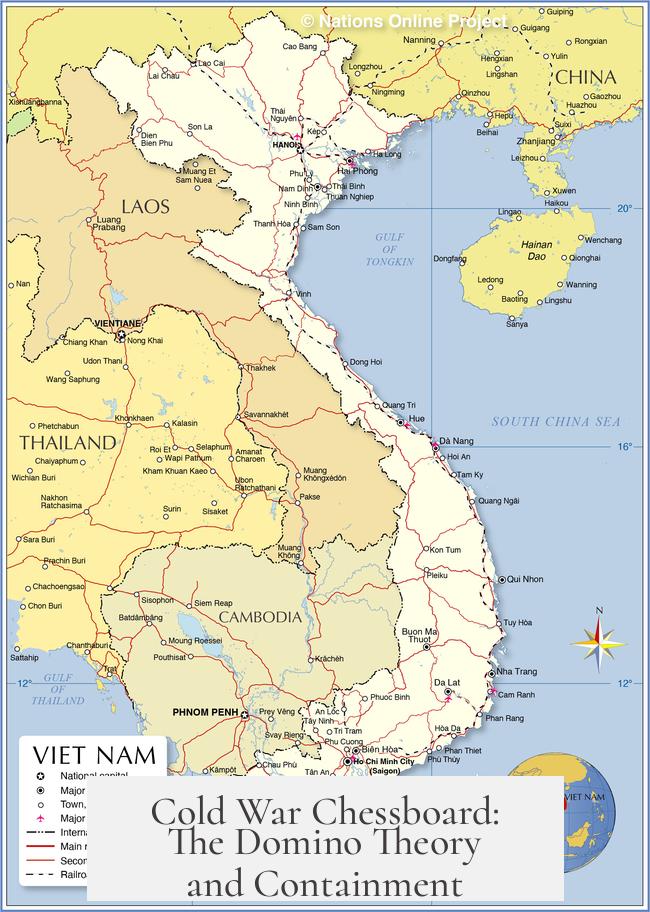

Cold War Chessboard: The Domino Theory and Containment

The U.S. saw Vietnam through a very different lens. Remember the domino theory? The idea was simple — if Vietnam fell to communism, neighboring countries would topple like a row of dominoes, spreading communism across Southeast Asia and threatening major nations like India and Indonesia. This threw the fear of 1949’s “fall” of China back into sharp relief.

America stepped in to “contain” communism — a policy aimed at keeping Marxist-Leninism boxed in. The Cold War wasn’t just about America vs. the USSR; it was a battle for global influence using proxy wars.

Victory or defeat in Vietnam was more than a regional matter; it symbolized whether communism’s tide could be halted or not. Protecting strategic regions like the vital Straits of Malacca — a crucial maritime channel for U.S. Pacific fleet operations — factored prominently in decisions. Letting countries fall to communism there risked greater military challenges by forcing the U.S. Navy to spread its fleet thinner across broader oceans.

America’s Objectives and the Military Reality on the Ground

American involvement started small in the 1950s with military advisors helping South Vietnam. By 1965, thousands of combat troops flooded in. The U.S. wanted to hold North Vietnam at bay long enough for South Vietnam to stand on its own feet — a limited mission, not a full-out invasion.

Hence, U.S. operations focused inside South Vietnam as well as Cambodia and Laos, since communist fighters used those areas for supply routes and infiltration. Despite overwhelming firepower, South Vietnam struggled economically, militarily, and morally to sustain itself.

This mirrors the challenges the U.S. would face decades later in conflicts like Iraq and Afghanistan, highlighting the difficulty of forcing democracy or government stability from the outside.

Other Players: Allies and Communist Supporters

The Vietnam War was a multilayered global affair. The Soviets and Chinese had stakes in seeing communist governments flourish in Southeast Asia to expand their ideological reach. China, in particular, viewed the region as a buffer zone vital to their border security.

On the other side, U.S. allies like South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand participated to repel communism and strengthen ties with America. Southeast Asian countries such as Thailand and the Philippines were part of SEATO, a collective security pact aimed at protecting the region.

France, having lost its colonial grip, left behind tangled political consequences. Ironically, French efforts to keep their empire convinced the U.S. of a looming communist “red avalanche,” which ended up accelerating the spread of communism into Cambodia and Laos — countries the U.S. didn’t directly conquer but whose fall was part of the feared domino cascade.

Who Really Won? The Outcomes and Legacy

To say the U.S. lost the Vietnam War is not just a matter of semantics — South Vietnam collapsed in 1975 after American funding was cut, and North Vietnam unified the country under communism.

Yet, this was a strategic masterstroke by North Vietnam. They outmaneuvered a wealthier, more populous adversary by leveraging global communist splits, like the Sino-Soviet rift, and hedging bets effectively. Few nations have beaten the U.S. strategically in such a way, proving superior political savvy and resilience.

Although the feared domino effect did occur partially, with Laos and Cambodia succumbing to communism, the spread didn’t engulf the entire region or major neighbors. Some claim the U.S. delayed communist expansion enough for other countries to strengthen defenses, but this remains hotly debated.

Lessons From the Vietnam War

Vietnam teaches us the limits of military power when lacking local legitimacy. The U.S. aimed to build a strong South Vietnam, but the government there couldn’t carry the weight. Was it really about communism? The Vietnamese people seemed more dedicated to sovereignty and anti-colonialism.

Could the war have been avoided if America focused on diplomacy instead of just military interventions? Or if the U.S. acknowledged the realities on the ground rather than chasing ideological fantasies like the domino theory?

Understanding Vietnam requires seeing it as a story of national pride squashed between superpowers playing global chess.

Wrapping Up: What Did It All Mean?

So, what was the point of the Vietnam War? It was a complex struggle to stop communism’s spread, protect strategic interests, and support government allies with questionable legitimacy. But for the Vietnamese, it was a fight for their nation — to end centuries of foreign domination and regain control over their own destiny.

Both sides fought fiercely, but ultimately, the people seeking independence and unity prevailed. Vietnam stands today as a reminder that history isn’t just about ideology or power plays — it’s about people striving for freedom, recognition, and peace.

And perhaps the greatest takeaway? Wars don’t just end when guns fall silent. Their true impact spreads far beyond battlefields, shaping nations and minds for generations.