The origin of the Patrician vs. Plebeian divide in the Roman Republic stems from early Roman history, rooted in social and religious distinctions established during Rome’s founding era. Patricians were initially a select group, possibly the heads of prominent families or those controlling priesthoods. Plebeians comprised the vast majority of free Roman citizens outside this elite circle.

Early archaeological finds support the existence of a settled community on the Palatine Hill in the 8th century BCE. According to Livy, Romulus established Rome and selected 100 leading families as patricians. This group maintained exclusive rights, including prohibitions on intermarriage with others, which legally separated them from plebeians.

Plebeians included all other Roman citizens—approximately 99% of the population. In Rome’s early Republic phase, plebeians could hold magistracies; Brutus, considered the Republic’s founder, came from a plebeian family. Over time, however, patricians began monopolizing offices during the 5th century BCE.

This growing imbalance sparked the Conflict of the Orders, a prolonged struggle between the classes. Legislations like the Licinio-Sextinian Laws (367 BCE) introduced reforms by mandating that one consul each year be a plebeian. The Lex Hortensia (287 BCE) granted laws passed by the Plebeian Assembly binding authority over all Romans, reducing patrician dominance.

The Lex Ovinia, also enacted in the 4th century BCE, empowered the Censor to control Senate membership, further diminishing patrician exclusivity. Eventually, political status depended more on holding magistracies and Senate membership than on patrician birth right.

By the late Republic, distinctions shifted. Senators who descended from ancestors with consulships formed the republican elite, the nobiles. The simple patrician-plebeian divide waned, replaced by status based on political achievement.

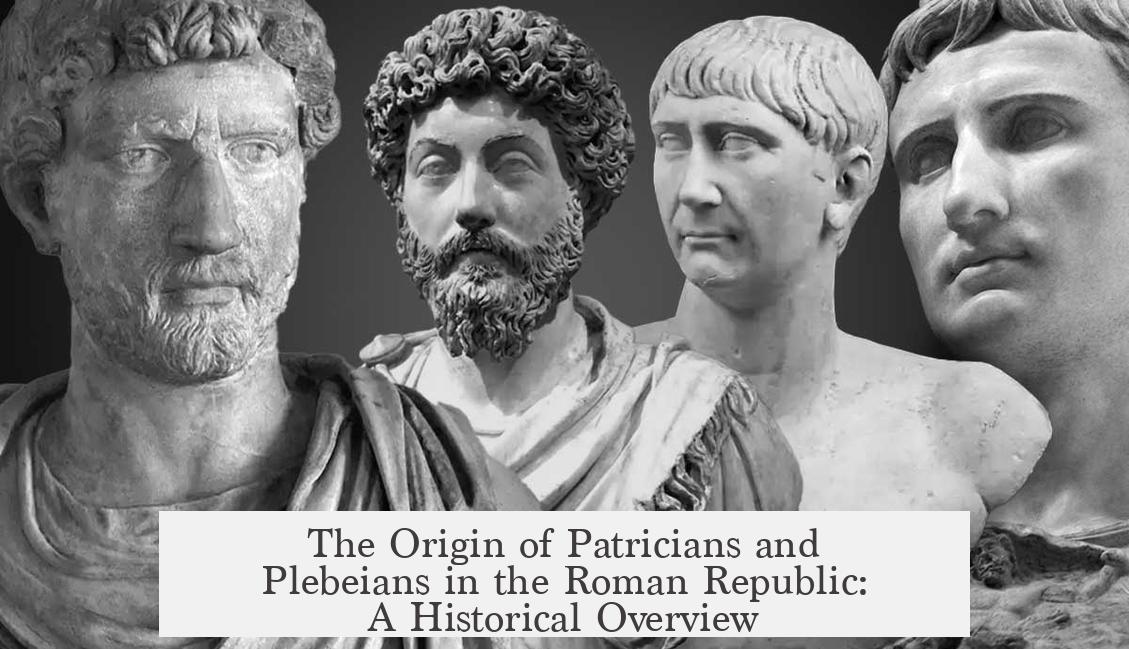

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Patricians | Originally select families, controlled priesthoods, banned intermarriage with plebeians. |

| Plebeians | Included all non-patricians, majority of population, initially held some magistracies. |

| Conflict of the Orders | Struggle for political equality; reforms gradually opened offices to plebeians. |

| Key Laws | Licinio-Sextinian (367 BCE), Lex Hortensia (287 BCE), Lex Ovinia (late 4th BCE). |

| Outcome | Political status based on Senate and magistracy; patrician-plebeian distinction declined. |

- Patricians originated as hereditary elite controlling religious and political power.

- Plebeians were the majority excluded from early privileges but gained political rights over centuries.

- The Conflict of the Orders gradually eroded patrician monopoly on offices.

- Legislations like Lex Hortensia gave plebeians legislative power.

- Over time, political rank, not birth group, defined Roman elite status.

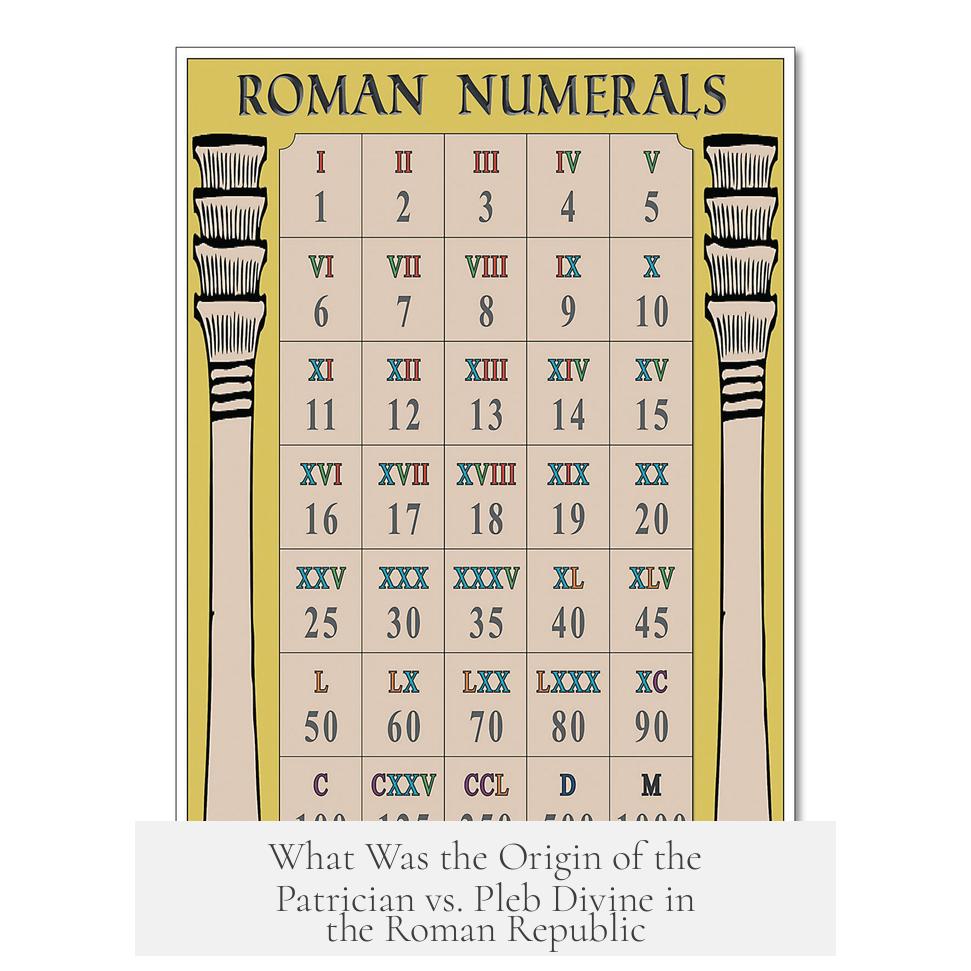

What Was the Origin of the Patrician vs. Pleb Divine in the Roman Republic?

To cut to the chase: The divide between Patricians and Plebeians in the Roman Republic started as a social and religious distinction rooted in ancient Rome’s earliest days—likely tied to control over priesthoods and ritual power. This division evolved into a rigid class system but eventually blurred through long political conflicts and reforms. Let’s unravel how this fascinating rivalry began and morphed over time.

Imagine Rome in the 8th century BCE—an expanding settlement on the Palatine Hill, bustling enough to bury its dead just outside town in the Forum Boarium (because no one likes a graveyard in their backyard). Archaeological digs support that people lived here—and died—long before emperors and senators strutted around in togas.

The Legendary Roots: Romulus and the Birth of Patricians

The story clicks on Romulus, one of Rome’s legendary founders. While tales like Romulus being raised by a she-wolf flirt with myth, ancient historian Livy offers a version that might be grounded. For example, Livy credits the fourth king, Ancus Martius, with founding Ostia, Rome’s ancient port. And guess what? An inscription backs that up. So maybe there’s some truth beneath the legends.

Now, about the Patricians—these guys or gals were supposedly the 100 original heads of Rome’s most prominent families, personally handpicked by Romulus. But here’s a twist: some scholars think it wasn’t just about noble lineage, but about who could hold priesthoods—those marquee religious positions that packed influence. In essence, if you controlled the sacred rituals, you controlled Rome’s soft power.

One key fact: the Romans made sure to keep Patricians a well-defined group. Laws forbade intermarriage with non-patricians, cementing their exclusivity. That’s a serious “keep out” sign in ancient Rome.

Who Were the Plebeians? The Other 99%

If Patricians were the elite club, Plebeians were everyone else—likely 99% of the population. They ranged from farmers and laborers to early magistrates. Fun fact: Brutus, one of the Republic’s founding heroes, hailed from a plebeian family.

Here’s a curveball: plebeians initially held some offices and had representation. But over the 5th century BCE, their presence in public office shrank dramatically. By the dawn of the 4th century BCE, patricians had locked down political and religious offices. This drift seeded a big social stain called the “Conflict of the Orders.”

The Conflict of the Orders: Plebs Fight Back

This conflict wasn’t a literal brawl but a political tug-of-war between Patricians and Plebeians. Plebeians demanded a larger role in governance and priesthoods, challenging Patrician monopoly.

The tug pulled hard until laws started tipping the scale:

- Licinio-Sextinian Laws (367 BCE): For the first time, one of the two annual consuls had to be a plebeian. Imagine this as breaking the “exclusive club” rule of who gets to be boss.

- Lex Hortensia (287 BCE): This was the game-changer—plebeian assembly laws became binding for the entire Roman population. Suddenly, plebeians wielded real legislative muscle.

- Lex Ovinia (late 4th BCE): Gave the Censor the power to admit or expel senators, further diluting patrician dominance.

Through these reforms, Plebeians chipped away at the Patrician fortress.

The Great Equalizer: Senate and the Rise of the Nobiles

Eventually, the sharp line between Patricians and Plebeians blurred. What mattered was not birthright but political office. To be a senator, you had to hold a magistracy—which now was open to both groups.

This shift created a new elite: the nobiles. These were families with consular ancestors, regardless of whether they had Patrician blood. Hence, in the later Republic, political power was less about old titles and more about accumulating prestigious offices.

Why Does This Matter Today?

Understanding the Patrician vs. Plebeian origin story reveals how power dynamics work. It’s not just about birth or wealth; control over religion and law mattered just as much—and political reforms reshape societies.

Plus, you have to admire the Romans: they turned a social conflict into a platform for expanding inclusion—slowly, but they did. It’s a historical lesson on how entrenched systems can change through laws and social pressure.

So, What’s the Real Takeaway?

The Patrician vs. Plebeian divide started as a religious-political distinction rooted in control of priesthoods and exclusive family lines. Over centuries, this hardened into social classes, only to be chipped away by plebeian activism and legal reforms, culminating in a more meritocratic elite defined by political office rather than birth.

In sum, it’s a story of struggle for equality, power plays, and the slow death of rigid class barriers.

Tips to Spot Patrician vs. Plebeian Dynamics Elsewhere

- Look for control over religious or symbolic institutions—this often signals deeper power struggles.

- Check if laws or customs restrict social intermingling (like marriage bans); that hints at class protectionism.

- Identify key reforms that open closed offices or bodies—these are usually markers of social change.

Like Rome, many societies start with such divides. How they navigate them often shapes their political and social legacy. So, next time you hear about ancient Rome, think less about togas and more about how power wrestles its way through religion, law, and politics.

What defined the patrician class in early Rome?

The patricians were originally seen as 100 leading family heads chosen by Romulus. Another view suggests they were those controlling priesthoods, which gave them religious authority and social power.

Who were considered plebeians during the early Republic?

Plebeians included everyone not patrician, likely about 99% of the population. Early plebeian magistrates, like Brutus, show they had roles, but their influence decreased over time.

How did the Conflict of the Orders affect patrician and plebeian rights?

This struggle gradually reduced patrician monopolies on offices and priesthoods. Key laws like the Licinio-Sextinian of 367 BCE allowed plebeians to become consuls, changing political power.

What was the significance of the Lex Hortensia in the patrician-plebeian struggle?

Passed in 287 BCE, the Lex Hortensia made laws passed by the Plebeian Assembly binding on all Romans, eliminating earlier patrician veto power and elevating plebeian influence.

Why did the patrician-plebeian distinction lose importance later in the Republic?

By the late Republic, being a senator mattered more than birth class. Senators came from both patrician and plebeian backgrounds who held magistracies, and political status based on ancestry with consuls became key.