Feudalism developed in medieval Europe primarily due to the power vacuum left by the fall of the Roman Empire, the need for protection during a violent era, and significant economic shifts. These causes combined to shape a social system based on land ownership, reciprocal obligations, and fragmented authority. This system structured medieval society and governance for centuries.

The collapse of the Roman Empire removed centralized authority across Europe. Without strong, centralized control, local strongmen emerged. These lords secured land and soldiers, forming private armies of knights. Ordinary people sought protection from these lords to survive in a dangerous world. This created the foundation of feudal relations, where lords offered security in exchange for service.

The medieval era was marked by frequent threats of violence. In such an unsafe environment, lords became vital figures, wielding military power. They protected serfs—peasants tied to the land—who, in return, provided labor or produce. This mutual dependence formed the core of feudalism.

Economically, kings granted large estates or fiefs to nobles. Initially, these holdings were not always hereditary. Over time, however, kings had to grant stronger rights to lords to secure their loyalty. This concentration of land into noble hands left peasants with few options. Gradually, free villagers became serfs—bound to live and work on a lord’s estate.

Earlier economic systems, like manorialism, involved peasants who could leave land. With feudalism, many peasants lost that freedom. Through ceremonies known as bondage, lords and new serfs formalized their relationship with oaths, defining duties and privileges. Serfs worked the land, growing food both for themselves and their lords, supporting the lord economically and socially.

Feudalism operated as a network of reciprocal obligations. Serfs labored and paid rent. Lords equipped themselves with expensive arms and trained knights to fight in wars for the king. These lords also provided local protection. This system of mutual support maintained social and military order.

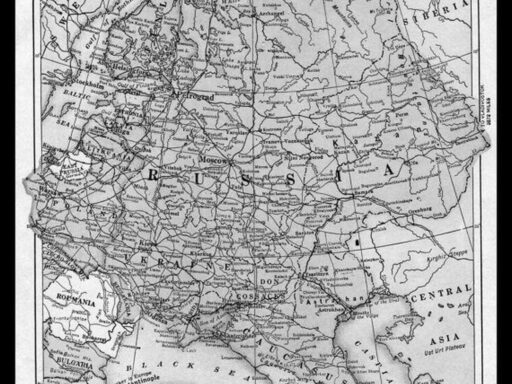

| Factor | Description |

|---|---|

| Power Vacuum | Collapse of Roman central authority led to local lords filling the void. |

| Need for Protection | Violence and instability increased demand for military defense from lords. |

| Economic Shifts | Land ownership concentrated in nobility; peasants tied to land as serfs. |

| Reciprocal Obligations | Serfs provide labor; lords provide protection and military service. |

| Decentralized Power | Layered lord-vassal relationships with oaths fragmented authority. |

| Church Role | Church reinforced local control and literacy, aiding stability. |

Feudalism also featured a decentralized political structure. Kings ruled large territories divided into regions controlled by lords, who swore loyalty up the chain. This created multiple layers of allegiances, fragmenting power but maintaining some order.

The Church played a crucial role by enforcing moral authority and literacy. It acted as a local power center, strengthening feudal control and administering justice in certain cases.

Feudalism’s development was unique to Europe’s social and economic context. Unlike the Byzantine Empire, which retained centralized authority and a cash economy, Europe’s post-Roman society lacked these features. The concept of Roman citizenship and a vibrant economy prevented the rise of similar systems elsewhere.

Social acceptance of feudalism arose because of chronic instability. Many peasants accepted serfdom as a better alternative to chaos. This acceptance mirrored modern cases where populations tolerate harsh regimes for stability.

Feudalism evolved from earlier Roman socio-economic institutions like the villa system. The Roman villa, where wealthy landowners controlled slaves, transitioned over time into manorial estates with serfs, setting the stage for feudal order.

- Feudalism emerged after Rome’s collapse due to lack of centralized power.

- Threats and violence made protection from local lords essential.

- Land ownership concentrated in nobility, binding peasants as serfs.

- Feudal contracts formalized duties between lords and serfs.

- Decentralized political structure relied on chains of loyalty.

- The Church supported local authority and stability.

- Unique conditions in Europe fostered feudalism, unlike other regions.

What Caused Feudalism to Develop in Medieval Europe?

Feudalism developed in medieval Europe mainly because the Roman Empire’s collapse left a power vacuum that made people crave protection, forcing a system of mutual obligations and land-based power to emerge. Now, that’s the one-sentence big idea. But this story? It’s far richer, messier, and—frankly—pretty fascinating.

Imagine Europe around the 5th century. The great Roman Empire, a superpower of the ancient world, crumbles like a poorly baked cake. Suddenly, the stable network of roads, armies, and administration that kept order vanishes. So what happens? Chaos. Bandits roam. Local strongmen flex muscles. The average Joe faces dangers on every side. What’s the solution? Feudalism.

The Power Vacuum: When Rome Exits the Stage

The Roman Empire’s disappearance doesn’t just leave empty castles. It leaves *no one* with clear authority. This vacuum makes common folks jittery. They can’t farm, trade, or live peacefully without someone to protect them. Enter the lords—strongmen who control chunks of land and can muster troops. They claim this power because they can protect the people—and that matters a lot more than having fancy titles from a distant empire.

So, land becomes the currency of power. Lords get land from shaky kings. Not initially handed down like family heirlooms, but these lords push for better and better deals to maintain their support. That land is the foundation of everything. No land, no power. No power, no protection.

Protection: The Medieval Must-Have

The medieval world isn’t a picnic. Attacks from rival lords, roaming invaders, and local disputes are a constant headache. Because lords have armies and knights, common people turn to them for safety. What do serfs get? Protection. What do lords get? Labor and service.

This deal—simple yet effective—is basically a social contract born out of necessity. Serfs farm some land for themselves to survive and work the lord’s land to keep this system afloat. The lord invests his free time and resources into training knights instead of tilling fields. This division holds society together.

Economic Realities: Land, Labor, and the Rise of Serfdom

At first, peasants aren’t tied forever to the land. They work in a system called manorialism, where free people can move about. But with time, this freedom evaporates. The lords’ all-encompassing landownership forces many freemen to become serfs. This isn’t just a social downgrade; it’s survival.

Serfdom often starts by force or necessity. In a ceremony called bondage, a peasant swears loyalty to a lord. In return for protection, they owe labor, produce, or both. This formal contract binds both parties and cements their places in the hierarchy.

It’s like signing a pact: “You protect me, I work your land.” Not glamorous, but sensible for unstable times.

Reciprocal Obligations: More Than Just Survival

Feudalism isn’t just about protection and labor. It’s about mutual obligations. A lord spends his free time sharpening swords and riding into battle for his king. Meanwhile, the serfs hustle on the land, making sure the lord can afford armor and horses.

This system doesn’t just keep enemies at bay; it creates a chain of dependencies. Lords rely on serfs for food; serfs rely on lords for defense. The mutual benefits make feudalism sticky and surprisingly resilient.

Decentralized Power: A Kingdom of Loyalties

The top dog, the king, technically owns all the land. But governance is like a giant nesting doll of loyalties. Large regions go to lords, who swear fealty to the king. Those lords parcel out smaller areas to vassals, who swear loyalty up the chain. The smallest lords owe allegiance to those above them.

This patchwork of power means no one has total control. It’s a complex web where personal loyalty matters as much as laws. While it sounds chaotic, it’s a practical solution to ruling a fragmented and unstable landscape.

The Church: Literacy, Stability, and Influence

The Church doesn’t just preach sermons. It keeps records, educates scribes, and acts as a pillar of local authority. Its widespread influence reinforces the feudal order. With literacy rare, the Church’s control of information cements its role as peacekeeper and moral guide.

In many ways, the Church is a silent partner in feudalism’s rise, spreading stability and control beyond mere swords and land.

Feudalism: Europe’s Unique Blend

You might ask, “Why didn’t this happen everywhere?” Look at the Byzantine Empire. It didn’t adopt feudalism. Why? Its economy was more cash-rich and vibrant. Also, Roman citizenship ideals made personal freedom more sacred. In Asia, societies rarely matched Europe’s feudal model. Even Japan’s Tokugawa period offers only a loose comparison.

So, medieval Europe’s feudalism becomes a case study in how specific economic and social pressures shape societies. Where money fails, land and loyalty rule.

Social Acceptance: Stability Over Freedom

Serfs didn’t love their situation, but stability beats chaos. Think about modern parallels—people tolerate harsh regimes if they bring order. Similarly, medieval Europeans accepted feudalism’s constraints because unpredictable violence was worse.

It’s a classic uncomfortable bargain: less freedom, more security.

Roots in Roman Society

Feudalism didn’t spring out of nowhere. It evolved from earlier Roman systems, particularly the villa economy—where rich landowners used slaves. After Rome’s fall, slaves vanish, but labor remains grounded in land control. Over time, slaves become serfs tied to manors, blending inheritance with new social realities.

Feudalism is partly a mutation of Roman institutions adapting to a new world.

Wrapping Up the Feudal Puzzle

Feudalism’s rise in medieval Europe is less about tradition and more about practical survival in a messy, fragmented world. The fall of Roman order creates a scramble for power. Constant danger demands protection. Lords offer land and security; peasants provide labor and loyalty. The Church backs stability. This system shapes Europe for centuries.

In a world lacking modern governments or economies, feudalism works—as flawed as it is. It answers the question of how people survive when chaos reigns. And that, perhaps, is its greatest legacy.

So next time you hear “feudalism,” don’t just think knights and castles—think of a complex social dance choreographed by power vacuum, protection needs, economic necessity, and human survival instinct.

What do you think was the most critical force in this feudal dance? Was it the compelling promise of protection, the harsh economic realities, or something else entirely? Drop your thoughts below!