The modern process for selecting a pope is highly formalized, involving the College of Cardinals convening in seclusion to elect the Bishop of Rome by a two-thirds majority. This procedure developed over centuries to reduce secular influence and ensure a clear, consensual outcome.

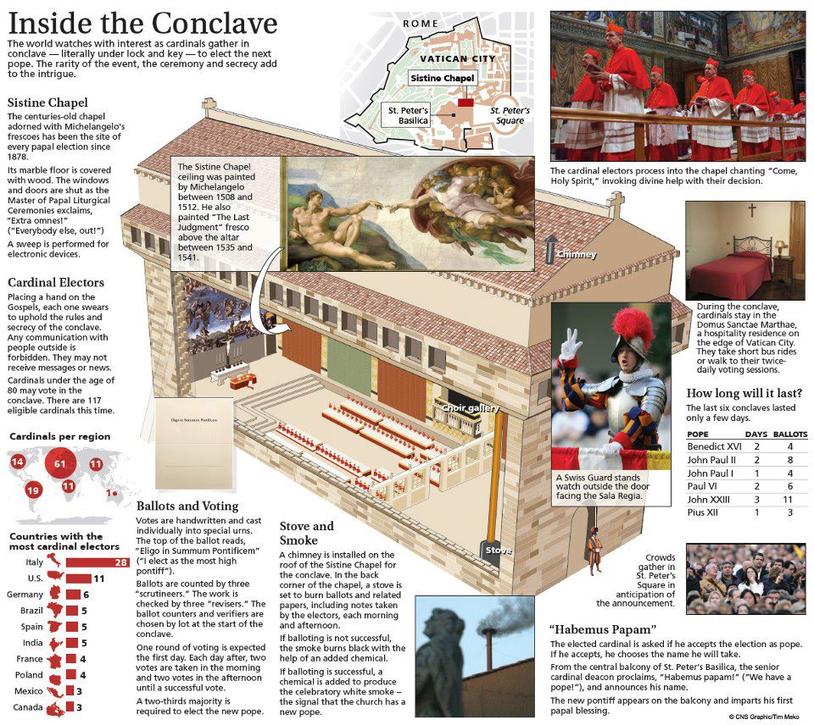

When a pope dies or resigns, the College of Cardinals—senior church officials appointed as titular heads of Roman churches—gather in the Sistine Chapel. They enter a conclave, locked away from outside contact, to discuss, pray, and vote in secret ballots. Voting rounds repeat until one candidate attains at least two-thirds of the votes. Each round’s ballots are burned, producing black smoke for no decision or white smoke to announce the new pope.

This solemn, tightly regulated method contrasts sharply with the early history of papal elections. In the first millennium of Christianity, papal succession was informal and lacked clear rules. Bishops of Rome were chosen through a mix of clergy and laity input. Emperors and local rulers often played direct roles.

In the early centuries, Byzantine emperors used their influence in selecting popes. Similarly, Frankish kings influenced appointments to align with their political aims. Powerful Italian noble families, such as the counts of Tusculum in the 10th and 11th centuries, dominated papal elections, even ensuring three family members became pope.

The Holy Roman Emperor also asserted control, appointing or vetoing candidates. Italian-born popes often came from territories under imperial sway. Even into the 20th century, some Catholic monarchs claimed veto rights. Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria exercised this at the 1903 conclave, blocking Cardinal Rampolla. Later, Franco unsuccessfully tried to veto Cardinal Montini in 1963.

The turning point came during the 11th century Investiture Controversy, a power struggle between the pope and Holy Roman Emperor over appointing church officials. This conflict culminated in the pope securing the right to appoint bishops and cardinals, largely free from secular interference.

Following these conflicts, the papal bull In Nomine Domini (1059) formally entrusted the College of Cardinals with exclusive papal election authority. This diminished imperial interference in Rome significantly.

Further reforms in the 13th century introduced the conclave’s seclusion rules. A notorious case was the nearly three-year vacancy (1268–1271), during which cardinals faced extreme conditions, including rationed food and removal of the meeting hall’s roof to pressure a decision. This episode led to stricter conclave regulations under Pope Gregory X.

Despite the formal setting, modern papal elections can still proceed rapidly. Cardinals typically know each other through decades of Church service, allowing informed decisions. Intense debate and prayer occur inside the conclave, often yielding consensus swiftly. The high two-thirds vote threshold ensures broad agreement on the new pope.

This evolution—from informal, secularly influenced selections to conclaved, cardinals-only elections—reflects the Church’s effort to protect its spiritual leadership’s independence while ensuring orderly, legitimate succession.

| Period | Election Characteristics | Key Developments |

|---|---|---|

| Early Centuries | Informal, heavily influenced by clergy, laity, and secular rulers | Emperors/crowds influence; lack of clear rules |

| 10th–11th Century | Noble families and emperors dominate; secular veto powers | Tusculum counts control popes; Investiture Controversy begins |

| 11th Century (Post-Investiture) | Cardinals gain election authority; reduced secular control | In Nomine Domini formalizes Cardinals’ role |

| 13th Century | Conclave seclusion and voting regulations introduced | Long interregnums lead to stricter conclave rules |

| Modern Era | Secret ballots by Cardinals locked in conclave; two-thirds majority | Smoke signals; rapid consensus; diminished secular veto |

- The College of Cardinals is the sole body electing the pope since 1059.

- Secular rulers once heavily influenced or controlled elections.

- The Investiture Controversy reduced secular power in church appointments.

- Strict conclave rules emerged after prolonged election deadlocks.

- Today’s conclave is secretive, formal, and often swift.

- Cardinals’ mutual knowledge and high voting thresholds foster consensus.

The Modern Process for Selecting a Pope and Its Remarkably Storied Past

So, how does the Catholic Church choose its leader today, and what wild roads did this careful process travel in centuries gone by? The modern papal election process is a tightly choreographed ritual mixing ancient tradition with urgent decision-making—but it wasn’t always that smooth. Let’s stroll through time together and explore how today’s conclave evolved from chaotic political chess matches involving kings, emperors, and power brokers into the solemn, formal ceremony it is now.

Picture the scene today: The pope steps down or passes on, and the College of Cardinals rally in Rome. Locked behind the vaulted ceilings of the Sistine Chapel, these senior church officials embark on a mission stirring equal parts intrigue, prayer, and strategy—casting secret ballots and awaiting the tell-tale puff of colored smoke announcing a new pontiff. But that neat process? It’s the result of centuries of trial, error, and power struggles.

What Happens in the Modern Papal Election?

First, the modern process demands order. The College of Cardinals, the pope’s elite circle, holds the exclusive right to elect the pope. Even if cardinals serve as archbishops or diplomats worldwide, canon law makes each a Roman priest in title, tying them to the See of Rome and cementing their eligibility.

Once the papacy is vacant, these cardinals lock themselves into the Sistine Chapel—no sneaking out for a pizza break or tweets allowed. They pray, debate, and cast secret ballots in repeated rounds. The charmed balance? Two-thirds majority needed to win. Each vote’s result is signaled by smoke from the chapel’s chimney—black smoke spells “No Pope Yet,” while white smoke shouts “We Have a Pope!”

This ritual is impressively efficient today. Sometimes it drags for several days, but that’s a blink in papal time. So how do cardinals, dispersed globally and numbering fewer than 120, manage this speed and coordination? Well, the answer lies in decades of service—they already know each other’s characters well. Decisions happen after intense prayer, debate, and informal networking before and during conclave, sharpening their votes to near-consensus.

But What About the Dark Ages and Before? Papal Elections Then

Flashback a millennium—or more. Early Christianity’s approach to picking the Bishop of Rome was far messier and far less formal. Records show unclear procedures, suggesting both clergy and laypeople had a hand in choosing the pope. Even powerful emperors and kings weighed in—sometimes handsomely influencing outcomes.

Byzantine Emperors dictated much at one point, while Frankish kings later played kingmakers. The golden crown often felt less spiritual, more political.

- Italian Nobles’ Puppet-Master Role: In the 10th and 11th centuries, powerful families like the Tusculum counts practically controlled papal appointments. This dynasty had not one, not two, but three popes from their clan! Imagine nepotism with a papal twist.

- Holy Roman Emperor’s Dominance: For decades, emperors handpicked popes, many of whom were technically “Italian” only because they were born within the empire. Politics blurred with piety.

- Veto Power by Catholic Monarchs: Even as recently as the 20th century, rulers flexed veto muscles. Emperor Franz Joseph’s veto stopped Cardinal Rampolla in 1903; Spain’s Franco tried to block Pope Paul VI in 1963 but failed. Secular meddling was a stubborn guest at the conclave table.

The Investiture Controversy: A Turning Point

The 11th century threw fire into this chaos with the “Investiture Controversy.” This crucible battle pitted Pope versus Holy Roman Emperor over who had the right to appoint church officials—bishops, abbots, and yes, indirectly the pope’s own allies. After decades of conflict, the pope mostly won. This victory became a foundation for the papacy’s spiritual sovereignty over church appointments, limiting secular tampering.

Still, secular rulers held sway over worldly affairs. But the church’s grip over its own hierarchy tightened, setting the stage for changes in papal elections.

Formalizing Electoral Authority: The Birth of the College of Cardinals’ Role

Enter the Papal Bull In Nomine Domini (1059), a game-changer. It officially vested the power to elect the pope exclusively in the College of Cardinals. This was a big deal. It ended a lot of external meddling, at least on paper.

The 13th century added even more structure. After a nearly three-year deadlock (yes, years!) between 1268 and 1271, cardinals faced pressure unheard of today. They were locked in with minimal food and even had the roof ripped off their meeting place during a scorching Roman summer! This not-so-gentle nudge finally pushed them to elect Gregory X, proving that seclusion fosters decision.

This rule of seclusion is still the heart of today’s conclave, ensuring cardinals focus purely on the task: choosing the next spiritual leader for 1.4 billion Catholics worldwide.

How Does Modern Speed Square with Tradition?

With roughly 120 cardinals scattered worldwide, one wonders—how can they quickly find common ground? They bypass the challenge of “Who’s that guy?” by knowing each other well. They’ve worked together for years in service, shared opinions, and engaged in debates long before the curtain closed.

Inside the conclave, intense debate and prayer proceed, but cardinals also engage in delicate political negotiations, much like any group with diverse interests trying to agree under pressure. The two-thirds majority rule means that no fringe candidate wins, boosting consensus.

This blend of pre-conclave diplomacy with spiritual discernment keeps the process both efficient and solemn. The system evolved to balance speed with the sacred weight of the decision—not an easy feat when appointing a global religious leader.

Why Does This Matter Today?

The modern formal process emerged from centuries of trial and error, secular meddling, and church reform. It’s a monument to resilience and adaptation. Understanding this history reminds us that the papacy’s present framework isn’t a static relic; it’s a living tradition forged in political battles, spiritual renewal, and human drama.

Next time you see that chimney puff black or white smoke, you’ll know it’s more than a signal. It’s centuries of history, prayer, politics, and hope, all rolled into a moment where the cardinals—their robes as recognizable as their resolve—come together to choose the spiritual captain of a multibillion-strong ship.

Final Thoughts: What Can We Learn?

- Power and Faith Intertwine: Papal elections show how spiritual authority and political influence have danced through history, shaping the Catholic Church and broader European culture.

- Consensus Matters: The two-thirds majority rule ensures no pope is picked lightly. It demands unity in a complex body of global leaders.

- Adaptation is Key: From brute-force nobility influence and emperor vetoes to secret ballots behind the Sistine Chapel walls, the Church’s election system evolved to meet changing times.

- Behind the Scenes: The conclave is less about surprise picks and more about careful vetting and long-term relationships.

Who knew choosing a pope could be so dramatic—and so meticulously ordered?

So, next time you wonder how an election of such magnitude happens relatively quickly, remember: it’s a ritual polished over a millennium, balancing holy duty with very human politics. The conclave’s smoke is a whisper of history, tradition, and the enduring quest to find the right shepherd for the world’s largest flock.

How did secular rulers influence papal elections before the modern conclave system?

Byzantine emperors, Frankish kings, and Italian nobles often shaped early papal choices. Powerful rulers could nominate candidates or veto those they opposed. This influence lasted into the 20th century, with some monarchs exercising veto rights.

What was the significance of the papal bull In Nomine Domini (1059)?

It formally gave the College of Cardinals exclusive rights to elect the pope. This decree reduced secular interference and centralized election authority within the church’s hierarchy.

Why are cardinals sequestered during the papal conclave?

Seclusion prevents outside influence and encourages focused discussion. This rule began after long election deadlocks, like the almost three-year conclave of 1268-1271 that ended only after pressure tactics like limiting food and exposure to the elements were applied.

How can cardinals decide so quickly on a new pope despite being from around the world?

Cardinals know each other well through years of service. Inside the conclave, they debate and pray intensely. The two-thirds majority rule ensures the election represents broad consensus among them.

What changed after the Investiture Controversy in the 11th century regarding papal elections?

The controversy ended much secular control over appointing church officials. The pope gained sole authority to appoint, which helped separate papal elections from imperial influence over time.