The deal with the Merovingian kings is rooted in their gradual loss of real power, evolving political fragmentation, and the rise of influential subordinates, notably the Mayors of the Palace. Despite holding royal titles, many late Merovingian kings became figureheads while real authority shifted away from the monarchy toward regional leaders and administrative officials.

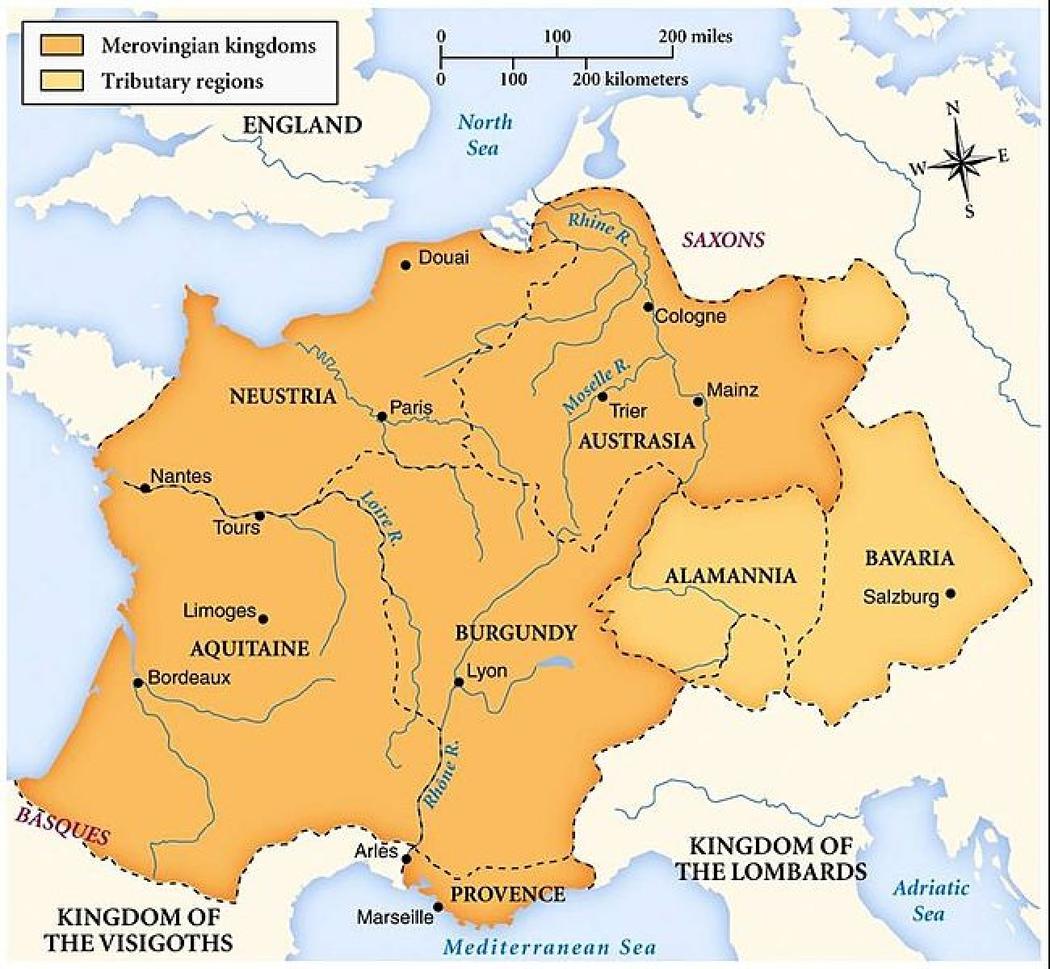

The Merovingian kingdom was never a tightly centralized state. Its political system consisted of multiple sub-kingdoms, such as Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy, each with strong local aristocracies. The Merovingian rulers nominally held authority over these territories, but in practice, power was dispersed regionally. The kingdom’s multi-king system reinforced this fragmentation, with several kings ruling different parts concurrently, creating overlapping but fragmented sovereignty.

In this context, centralization could only be achieved by force, often through military campaigns, and required cooperation with the nobility. The Mayors of the Palace—initially royal household officers—began accumulating military and administrative power. By the early 8th century, they became the real power brokers behind the throne, while kings, often young or weak, retained mostly ceremonial roles.

This fragmentation and power shift are exemplified by the growing dominance of Austrasia, one of the sub-kingdoms located in the northeast, around modern Belgium. The local magnates, particularly the Pippinids (ancestors of the Carolingians), consolidated their influence here. They built networks of power independent from royal favor, controlling land, monasteries, and local aristocrats. This regional clout allowed figures like Charles Martel to emerge as dominant leaders, ultimately eclipsing the Merovingian kings.

Carolingian-era historians like Einhard provide a retrospective view, often portraying late Merovingian kings as rois fainéants—“do-nothing kings.” They suggest these monarchs lacked vitality and were sidelined by the mayors who wielded true authority. However, modern research reveals a more nuanced picture. Some kings, such as Clovis IV, Childebert III, and Dagobert III, still exercised judicial authority and issued official documents, signaling ongoing, if diminished, royal functions.

The shifting socio-economic landscape also influenced Merovingian decline. The rising importance of North Sea commerce and river traffic through the Rhine and Meuse valleys supported the ascendancy of Austrasia and its Pippinid leaders. These economic changes provided resources and networks that empowered regional magnates over distant monarchs.

Another factor destabilizing royal power was the royal faida—a paralegal vendetta tradition between Merovingian heirs and noble factions during the late 6th and early 7th centuries. This prolonged internal strife, marked by assassinations and power struggles involving queens, aristocrats, and bishops, undermined monarchy cohesion. The resolution under Chlotar II reinforced regional courts and aristocracies, further entrenching decentralization.

Throughout the 7th century, the aristocracy changed. Romanized elites gave way to more militarized noble families focused on personal and familial interests rather than public service. Bishops retained some traditional administrative roles but increasingly blended religious authority with secular power. Kings like Chlotar II and Dagobert I retained some control, especially over appointments and fiscal policies, but their reach weakened against regional forces.

The short reigns and early deaths of several Merovingian kings in the late 7th century created repeated regencies and royal minorities. These periods allowed Mayors of the Palace to expand their power. Majordomos acted as indispensable intermediaries between the king and regional aristocracy, managing court affairs and securing loyalty. Figures like Erchinoald in Neustria and Grimoald in Austrasia held de facto leadership while maintaining the façade of royal authority.

By the 8th century, this dynamic reached a tipping point. The accumulation of military power, land, and networks by the mayors, alongside weakened kingship, led to the fall of the Merovingians. The Carolingians, starting with Charles Martel, effectively became rulers. The kings remained symbolic heads, but the true power rested ‘behind the throne.’

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Political System | Fragmented with multiple sub-kingdoms; decentralization favored regional aristocracies. |

| Role of Kings | Titled monarchs but often ceremonial, overshadowed by powerful mayors and nobles. |

| Mayors of the Palace | Shifted from household officials to military and administrative leaders, controlling real power. |

| Economic Context | North Sea trade and river routes empowered northeastern regions and local magnates. |

| Royal Faida | Extended internal conflicts weakened monarchy and empowered regional courts. |

| Carolingian View | Portrayed Merovingians as weak kings to legitimize Carolingian takeover, but recent studies offer complexity. |

- The Merovingian kings’ power declined due to decentralization and internal fragmentation.

- Mayors of the Palace emerged as true rulers, reducing kings to symbolic roles.

- Economic shifts favored regional powers like Austrasia and the Pippinids.

- Extended aristocratic conflicts eroded royal authority and stability.

- The Carolingians later portrayed Merovingians as weak to justify their own rise.

So, what’s the deal with the Merovingian kings, anyway?

The Merovingian kings weren’t just old-time monarchs lounging on thrones; they were part of a deeply fragmented and evolving power structure where real control often slipped from their hands to powerful regional players known as the Mayors of the Palace.

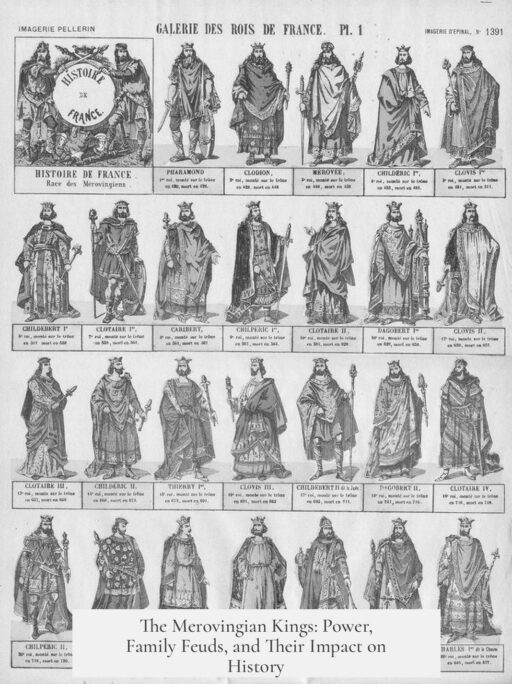

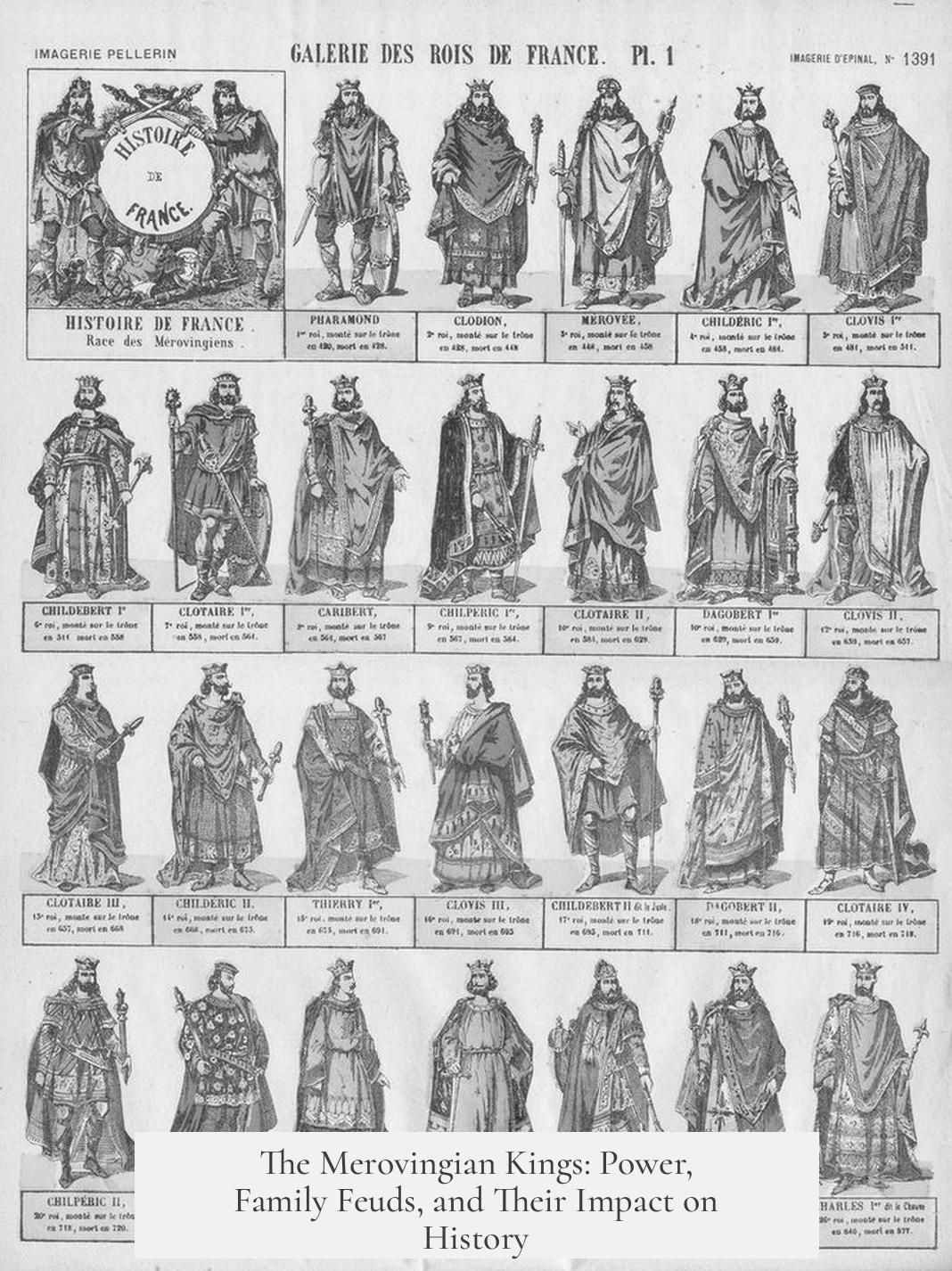

Sounds confusing? Well, buckle up. The Merovingians ruled a sprawling realm in early medieval Europe — think of them as the first big-name Frankish dynasty, starting with Clovis I in the late 5th century. But by the 7th and 8th centuries, things got tricky. Power was no longer simply centralized in the king’s hands; it was scattering across regions and influential nobles. Let’s unpack this fascinating political drama and see what the Merovingian kings were actually up to.

The Great Power Shuffle: Devolution and Regionalism

From the get-go, the Merovingian political system wasn’t your neat, centralized kingdom. It was fragmented — fragmented enough to feel like playing a board game where multiple kings and sub-kings jostle for power. Think of this as a “multi-king system” where power was already regionalized. Unlike how we think kings ruled absolute kingdoms later on, Merovingian rulers shared their domains, and their reign was intertwined with local aristocrats and sub-kings.

For example, the capital wasn’t the only center of control. Over time, power shifted away from the capital to various regional strongholds, especially the sub-kingdoms of Austrasia, Neustria, and Burgundy. Austrasia, located in what is now Belgium and parts of Germany and France, notably gained increasing dominance thanks to the rise of powerful families like the Pippinids, later known as the Carolingians.

Power wasn’t something the kings could just assert; it needed reinforcement through war and alliances. Charles Martel, one of the most famous Merovingian-era figures, exemplified this. His military campaigns, particularly conquering southern territories, gave him leverage. But guess what? Even he was officially Mayor of the Palace—not king—and true military power rested with those Mayors.

Mayors of the Palace: The Real VIPs

Here’s where it gets juicy. The ‘majordomos’ or Mayors of the Palace began as high-ranking officials managing the royal household. But by the late Merovingian era, they morphed into the real rulers.

Einhard, the historian who later chronicled Charlemagne’s reign, didn’t hold back in his depiction of the late Merovingian kings. He described them as the rois fainéants — literally, “do-nothing kings.” According to him, these kings had the title but not the power. The Mayors ran the show, handled resources, led armies, and controlled appointments.

“Indeed, nothing was left to the king except to be happy with the royal title and to sit on his throne with his flowing hair and long beard and to behave as if he had authority…” — Einhard, The Life of Charles the Emperor

But hold on — this narrative mostly comes from Carolingian sources who had every reason to depict their predecessors as weak to legitimize their own power grabs. Modern historians urge caution and point out that some late Merovingian kings still exercised real authority, especially judicial and religious authority.

Evidence of Merovingian Royal Power in Late Period

Take King Childebert III (r. 694-711). Despite the repute of powerless kings, Childebert issued numerous royal documents, including judicial records. In a famous case from 710, he favored the monastery of St. Denis over the mighty Mayor Grimoald of Neustria. Such acts remind us these kings wielded influence—not always just figureheads.

This judicial power hadn’t entirely vanished, though it was increasingly overshadowed by the practical military and fiscal control held by the Mayors of the Palace and the regional aristocracy.

The ‘Royal Faida’: Not Your Average Family Feud

The Merovingian realm wasn’t short on drama. From the late 6th to early 7th centuries, it underwent the ‘royal faida,’ a drawn-out, brutal series of conflicts among royal successors.

This royal feud was no soap opera but a complex, multi-decade bloodletting rivaling the Hundred Years War in intrigue and chaos. Queens Brunhild and Fredegund led vicious factions. Assassinations, betrayals, and foreign interference were par for the course.

While King Chlotar II eventually emerged victorious, the conflict fragmented royal power, entrenched regional aristocracy, and codified the tripartite kingdom’s core divisions: Neustria, Austrasia, and Burgundy. The aristocracy aligned itself with their regional courts, making centralized royal control even harder.

Aristocracy on the Rise: Changing Faces and Interests

The power shifts also touched the aristocracy itself. The traditional, Roman-influenced elites didn’t disappear but saw significant changes.

By the late 6th century, the nobility became more warlike and individualistic, focusing on family interests over public service. Bishops, on the other hand, took on more administrative roles, inheriting some of the senatorial traditions and becoming influential in both church and state affairs.

This evolving social structure created a complex mesh of loyalties and responsibilities. Political power was increasingly negotiated among a powerful aristocracy spread across the regions, with the king often acting as a referee rather than an all-powerful ruler.

Regional Power Dynamics: Austrasia’s Ascendancy and the Pippinids

Among the sub-kingdoms, Austrasia took center stage, a shift that marked a decisive change in Merovingian politics. Prior to the 6th century, Neustria held dominant networks of power and wealth. However, Austrasia became the frontier kingdom where new elites thrived.

The Pippinids, ancestors of the Carolingians, cultivated vast landholdings, noble alliances, and controlled important monasteries in the Moselle and Meuse river valleys. They operated with near independence from royal favor, signaling their rising clout.

Interestingly, Charles Martel, a Pippinid and the eventual stopgap to Merovingian power, was probably the illegitimate son of Pepin of Heristal and a local noblewoman from the Maastricht area. His roots reflect this regional power base linked to prosperous North Sea and river trade routes.

Socio-Economic Winds: The North Sea Factor

Economics also played a crucial role. The rising importance of North Sea commerce and river traffic around the Rhein-Maas area fueled political changes. Control over trade increasingly meant control over resources, armies, and political loyalty.

The Frisian petty kingdom, situated at these river mouths, served as a vital link between Gallia, Great Britain, and Scandinavia. With the Franks expanding their influence over the Frisians after 700, the economic foundations for political power shifted.

This commercial boom wasn’t just about money; it created a network of local magnates and connected elites that challenged traditional royal authority but eventually underpinned the Carolingian rise.

Challenges to Royal Authority and Military Stature

While kings like Chlotar II and Dagobert I managed to consolidate some power and force tribute from groups such as the Saxons, they faced difficulties in subduing the Vascones, Bretons, and Slavs. In fact, some confrontations weakened royal prestige when royal armies suffered defeats.

The lack of military successes and the inability of late Merovingians to effectively handle border threats further eroded their authority. The aristocracy and the Mayors saw opportunities in these failures to expand their own influence over military and fiscal resources.

Succession Crises and the Rise of the Majordomos

The ‘royal turnover’ in the second half of the 7th century played a big role in the dynasty’s decline. Successors of Dagobert I, such as Sigebert and Clovis, died young, usually under the tutelage of powerful queen mothers and aristocrats. These short reigns didn’t breed stable royal power networks.

Meanwhile, majordomos became indispensable as intermediaries between the king and the powerful nobility. Their authority was partly inherited and partly earned through prowess and networks. Some, like Grimoald of Austrasia, rose to significant power—saving kings and eliminating rivals.

Though the kings remained nominal heads, these powerful officials gradually took charge. Their long tenure in office, control over resources, and role as power brokers were accepted by the nobility. The majordomos, in many ways, shaped the kingdom’s destiny without holding the royal title.

Putting It All Together: What Really Happened to the Merovingian Kings?

So, what’s the real deal with these kings everyone calls “do-nothing”? It’s a mix of truth, exaggeration, and perspective. The Merovingian kings ruled a patchwork kingdom with intense regionalism and aristocratic influence. Over time, the structure evolved where kings kept symbolic roles but gradually lost their grip on military power and administrative functions.

The rulers relied heavily on collaboration with powerful regional nobles and the aristocracy, who themselves changed, becoming more warlike and self-interested. The rise of Mayors of the Palace shifted the de facto leadership from kings to these powerful officials, especially in Austrasia with the Pippinid family.

Yet, the kings still had moments of authority—issuing judicial rulings and managing religious institutions. They weren’t merely puppets, but their power was limited and declining. Economic shifts and military challenges hastened this loss of influence.

Ultimately, the Merovingians set the stage for the Carolingians, who capitalized on the regional power struggles, economic changes, and military conflicts to seize control. Charles Martel’s triumphs and his lineage’s rise to kingship crowned this transition.

Why Care About the Merovingians Today?

Understanding this nuanced story paints a richer picture of early medieval Europe beyond dry lists of kings and dates. It reveals how power plays, economics, family dynamics, and evolving social structures shape history’s flow.

And, if you love a long-running saga of political intrigue with backstabbing queens, ambitious nobles, and tactical officials outsmarting kings, the Merovingians have you covered. They remind us even kingship isn’t always what it seems, especially when the real rulers lurk behind the throne.

So, next time you hear about the ‘do-nothing kings,’ think twice. Those flowing beards and throne-sitting acts hid a complex world of power negotiations and historical transitions that shaped medieval Europe’s future.

What led to the decline of Merovingian royal power?

Power shifted from the kings to the Mayors of the Palace. Military strength and real control moved to regional leaders. Kings became mostly ceremonial, losing direct influence over governance.

Why were Merovingian kings called “rois fainéants”?

This term means “do-nothing kings” and comes mainly from Carolingian historians like Einhard. They portrayed late Merovingian kings as powerless, with real authority held by palace mayors.

Did late Merovingian kings still have some authority?

Yes, kings like Clovis IV and Childebert III issued numerous judicial documents. In some cases, they exercised influence over regional leaders and monasteries despite weakened overall power.

How did regional divisions affect Merovingian rule?

The kingdom was split into sub-kingdoms like Austrasia and Neustria, each with its own power centers. This fragmentation made centralization difficult and strengthened local magnates.

What role did economic factors play in the Carolingians’ rise?

The growth of North Sea trade and control over river routes boosted regions like Austrasia. The Pippinid family leveraged this economic power, leading to Carolingian dominance over the Merovingians.