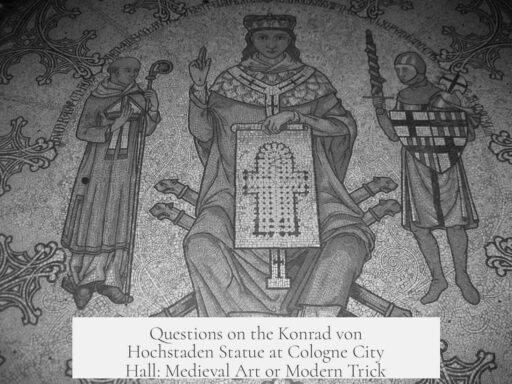

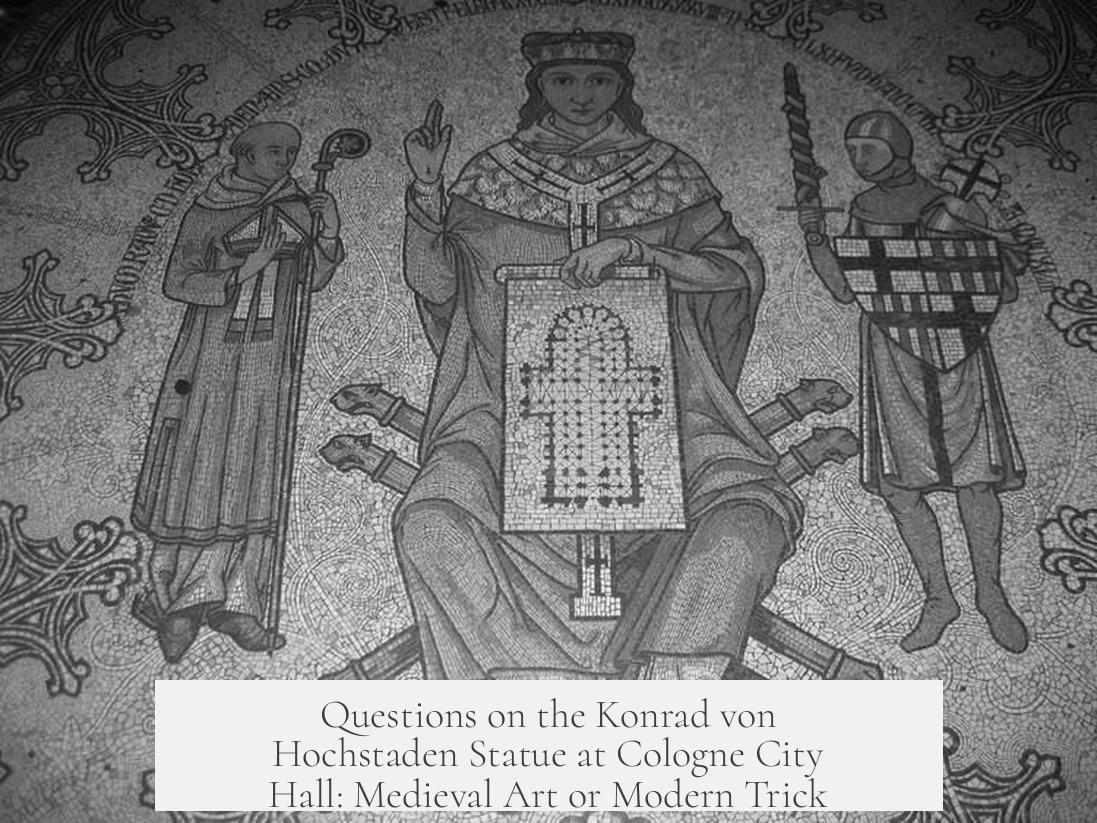

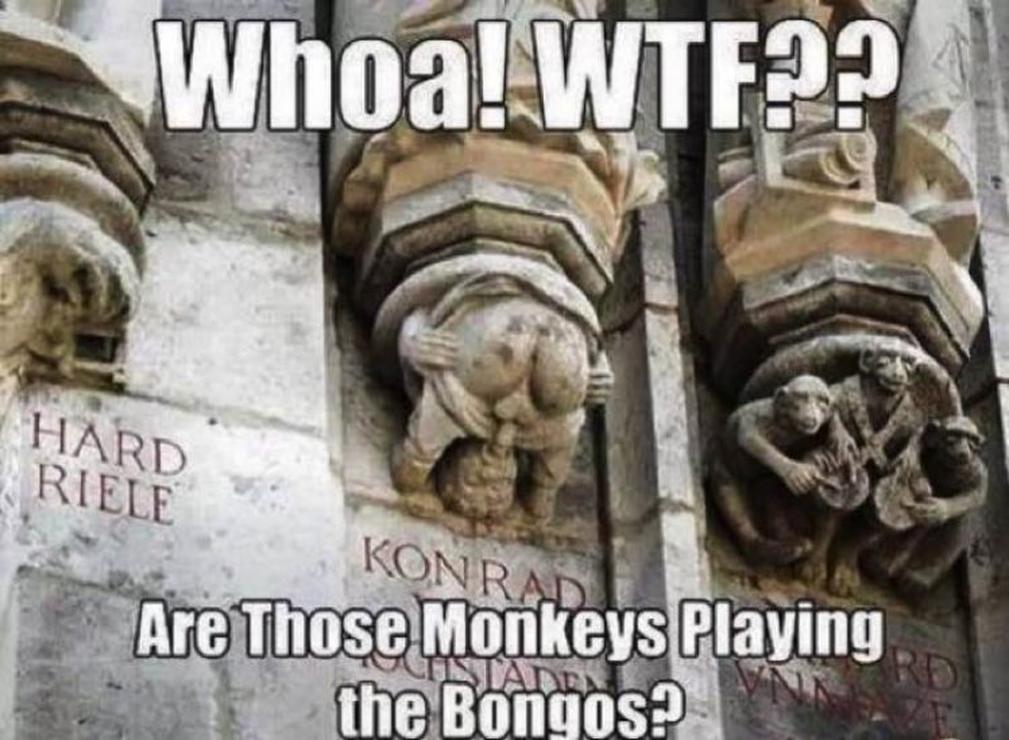

The statue of Konrad von Hochstaden on the walls of Cologne City Hall features bizarre and seemingly absurd artistic elements typical of medieval marginal art. This statue, along with adjacent sculptures such as monkeys playing bongo drums, belongs to a tradition that integrates scatological, sexual, or playful imagery in lesser-seen parts of medieval artworks.

Medieval art does not strictly separate sacred and profane subject matter as modern viewers might expect. Rather, the location within the artwork dictates acceptability. Explicit or crude images that would be inappropriate as main scenes often appear in marginal spaces like column capitals, misericords, or statue bases. These marginal images provide a visual counterbalance and inject folk or popular culture themes into official art.

Some experts propose these grotesque or profane depictions served to acknowledge the coexistence of good and evil, sin and virtue. They also might reflect a societal effort to incorporate the demonic and monstrous into public consciousness through art. Thus, the Konrad von Hochstaden statue’s peculiar figures exemplify a widespread medieval artistic convention rather than a singular oddity.

This particular statue’s stone coloration suggests possible modern restoration or imitation. Restoration projects sometimes honor medieval marginal traditions by adding humorous or profane carvings. An example is the inclusion of modern pop culture symbols like Darth Vader on the National Cathedral’s gables. This practice keeps alive historic intentions of blending official and popular visual elements.

For readers interested in this subject, literature like Michael Camille’s Images on The Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art and Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches explores these themes extensively.

| Key Points |

|---|

|

Questions about the Statue of Konrad von Hochstaden on the Walls of Cologne City Hall

What’s up with the eccentric statue of Konrad von Hochstaden on Cologne City Hall’s walls? Glad you asked. This statue is not your ordinary noble figure standing stoically. Instead, it boldly strolls into the realm of weird and whimsical medieval art, blending history with bizarre and even cheeky imagery. Let’s unpack its uniqueness and what it tells us about medieval art—and maybe even modern creative nods.

First, this statue sits amidst a slew of curious sculptures, some featuring monkeys beating bongo drums. Yes, monkeys drumming away as if they’re on percussion duty for the Cologne City Hall’s quirky medieval parade. This seemingly absurd choice is no accident but a signature trait of what art historians call “marginal art” in the medieval period.

Marginal art lives on the edges—literally. Artists of the Middle Ages used spaces like column capitals, misericords (the little ledges under church seats), manuscript margins, and even statue bases to insert all sorts of playful, bizarre, or crude images. These quirky designs could be scatological, sexual, eerie, or simply silly. The statue of Konrad von Hochstaden fits right into this tradition, a bit of comic relief carved in stone.

The Curious Placement of Bizarre Imagery in Medieval Art

You might wonder why such irreverent motifs appear alongside religious or serious subjects? Medieval art lacks our modern strict division between sacred and profane. Instead, importance lies in the artwork’s spatial hierarchy. Artists could safely include coarse or crude scenes at the artwork’s margins without offending viewers’ spiritual sensibilities.

A lewd or strange scene would be upsetting as a centerpiece on a sacred altarpiece, but nestled discreetly in a corner or on a statue’s base, it became acceptable—even expected. There’s a layered storytelling here. The main panel preached virtue, while the margins showcased humanity’s raw, sometimes sinful realities. In this way, marginal images like those around the Konrad von Hochstaden statue provide a richer cultural snapshot than grand, formal art alone.

Is It Medieval or a Modern Prank?

Now, a sharp eye might notice that the statue’s stone coloring looks fresher. Could this be a modern creation camouflaged in medieval style? Or part of restoration work? Restorers sometimes honor historical tradition by adding new whimsical carvings that fit the old pattern—sort of like sneaking a Darth Vader cameo onto a Gothic cathedral, as seen at the National Cathedral in Washington D.C.

If that’s the case here, the modern artist is tiptoeing on a grand tradition of mixing sacred and profane, serious and silly, old and new—signaling that this kind of playful marginal art is still alive in our collective imagination.

What Do Scholars Say About These Odd Marginal Figures?

The meaning behind such grotesque or bizarre images remains a lively topic. Some scholars suggest these carvings gave a voice to popular or folk culture alongside official, church-sanctioned art. Others see the monstrous or sinful figures as acknowledgments of life’s darker sides—demonic temptations, the grotesque, and evil—articulated openly in public spaces.

Think of it as medieval society’s way to balance life’s highs and lows. It wasn’t all angelic halos; sin and humor had their place too, even if tucked away in the margins. These images remind us that medieval art embodies a broad artistic tradition—not isolated jabs or accidents. It’s intentional, serving both spiritual and social functions.

Konrad von Hochstaden Statue: A Window into a Broader Tradition

Far from being a random oddity, the statue joins a lineage of medieval artworks that proudly blend the bizarre with the noble. Its presence on Cologne City Hall’s walls enriches the building’s narrative—history comes alive not only through facts but through the humor and human quirks immortalized in stone.

So the next time you see the monkey drummers, or the strange oddities surrounding Konrad von Hochstaden’s statue, see it as a lively conversation across centuries—between serious history and colorful human imagination.

Want to Dive Deeper?

Fancy a deeper dive into the margins of medieval art? Michael Camille’s Images on The Edge: The Margins of Medieval Art offers a brilliant exploration. Also, Images of Lust: Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches delves into the boldly risqué side of medieval creativity.

These reads explain why medieval architects and artists didn’t just build and paint—they created layered, multi-voiced worlds where even the weird and silly told stories worth hearing.

“Art in the margins is life made visible—the unfiltered, unpolished, and utterly human. In stone.”

So, is the bizarre statue of Konrad von Hochstaden a mere odd decoration? Far from it. It’s a fascinating key to medieval culture, where sacred and profane mingle in a stone tapestry filled with surprises. What was once hidden to some eyes now invites us all to explore the richness and complexity of artistic tradition on the walls of Cologne City Hall.

What does the statue of Konrad von Hochstaden on Cologne City Hall depict?

The statue includes bizarre and absurd elements, like playful monkeys on drums. This fits with a medieval art style that mixes the scatological, sexual, and silly in less central parts of artworks.

Why are such strange images placed on the walls of Cologne City Hall?

Medieval art often uses marginal spaces for crude or lewd images. These details appear on edges or bases where they balance sacred main scenes without offending viewers directly.

Could the statue of Konrad von Hochstaden be a modern addition?

Its fresh appearance suggests it might be from restoration work. Such restorations sometimes copy medieval habits by adding playful or profane figures to honor the old style.

What do scholars say about the purpose of marginal medieval art like this statue?

Experts think such art blends official culture with folk ideas. It may represent evil or sin alongside virtue, showing complex views of life and morality in public art.

Where can I learn more about marginal medieval sculptures and carvings?

For detailed study, read Michael Camille’s books, especially _Images on The Edge_ and _Images of Lust_. They explore the strange and sexual carvings found in medieval churches and artworks.