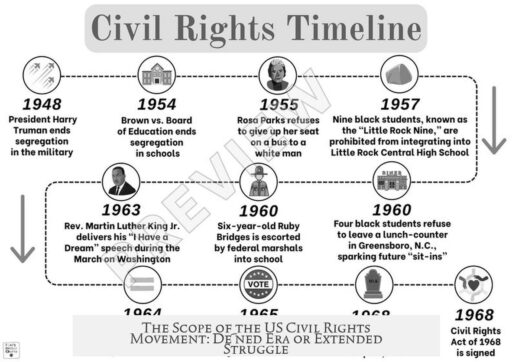

The US Civil Rights Movement is better understood as a longer, less defined period of time rather than a fixed period from 1954 to 1968. While the traditional view dates the movement from the landmark 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision to the Fair Housing Act of 1968, modern scholarship and activists argue for a broader scope. This expanded timeline acknowledges decades of activism before 1954 and recognizes struggles that continued well beyond 1968.

The traditional period (1954-1968) centers on significant legislative and judicial milestones. It begins with the Supreme Court decision ending school segregation in Brown v. Board and closes around the passage of the Fair Housing Act. This range captures major civil rights victories and some of the most visible mass protests, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the March on Washington.

Despite its convenience, this narrow timeline has important limitations. It risks oversimplifying a complex movement whose roots extend far back and whose effects continue to resonate. Moreover, it tends to focus on landmark figures and events while neglecting ongoing activism and broader political fights. For example, the enforcement challenges of the Fair Housing Act persisted for decades, illustrating that legal victories did not end the struggle.

Historians like Jacquelyn Dowd Hall propose the idea of the “Long Civil Rights Movement.” This conceptual framework pushes the timeline back to the 1930s or earlier. It highlights organizing, legal battles, and grassroots efforts by pioneers like Ida B. Wells, W.E.B. Du Bois, and the NAACP. These efforts laid the groundwork that later produced the mid-20th-century breakthroughs.

The Long Civil Rights Movement also explores political dynamics often overlooked in the shorter narrative. It discusses connections between civil rights activists and leftist groups, including Communists, which influenced the debate and provoked conservative backlash labeling civil rights as communist-inspired. This complexity offers deeper insight into opposition faced by activists.

The limited timeframe is also criticized for creating a sanitized, simplified narrative centered on Martin Luther King Jr., especially focused on his “I Have a Dream” speech of 1963. This portrayal freezes King in a moment of hopeful rhetoric, ignoring his later radical critiques of war, economic injustice, and entrenched northern segregation. King’s opposition to the Vietnam War, advocacy for workers’ rights, socialism, and his Poor People’s Campaign show a broader, more challenging activism beyond the 1954-1968 window.

This narrow focus contributes to what some call “whitewashing.” It avoids uncomfortable topics such as reparations and LGBTQ+ rights, which fall outside the simplified civil rights mythos. By restricting the movement to racial equality and key public moments, the broader issues of systemic inequality and intersectional justice receive less attention.

People who maintain the traditional timeline may do so unintentionally or from habit rather than malice. However, the choice of dates shapes who belongs to the civil rights story and which struggles get recognized or sidelined. The exclusion of early activists and later movements affects public understanding and policy discussions.

- The traditional Civil Rights Movement is often dated from 1954 (Brown v. Board) to 1968 (Fair Housing Act).

- This timeline highlights landmark legislation and peak moments of mass protest.

- Critics argue this frame is too narrow and excludes decades of prior activism.

- The “Long Civil Rights Movement” includes efforts from the 1930s and activists like Ida B. Wells and W.E.B. Du Bois.

- Key figures like Martin Luther King Jr. are often simplified to a 1963 speech, missing his later radical views.

- The narrow definition can obscure broader civil rights issues, including reparations and LGBTQ+ rights.

- Debate continues as the civil rights story evolves with new scholarship and social movements.

The civil rights movement, therefore, is best seen as a complex, ongoing struggle. Its boundaries depend on the lens applied. From early 20th-century activism through major victories in the 1950s and 1960s, and continuing efforts addressing inequality today, it resists a simple timeframe. Recognizing this fuller narrative deepens understanding of American history and civil rights challenges.

Is the US Civil Rights Movement a Defined Period of Time (1954-1968) or a Longer, Less Defined Period?

Simply put, the US Civil Rights Movement isn’t easily boxed into the neat timeframe of 1954 to 1968. Instead, it’s a dynamic, evolving story that stretches across decades — before and after those key dates. That said, many still cling to this narrower window thanks to convenient landmarks, but the reality is far richer and more complex.

Let’s take a stroll through history and unpack why pinning down the Civil Rights Movement to a tidy era often misses the broader, ongoing struggle for justice and equality.

Why 1954–1968? The Traditional View

So, what’s with the years 1954 to 1968? This period gets spotlighted mainly because it starts with Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the Supreme Court ruling that declared school segregation unconstitutional, and ends with the 1968 Fair Housing Act, an important civil rights law against housing discrimination.

These years mark some of the movement’s biggest wins: the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the March on Washington, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It’s an era packed with landmark moments.

But, as one historian notes, ending in ’68 conveniently skirts ongoing struggles—like how the housing law’s enforcement lagged for decades, with figures like George Romney pushed out for trying to apply it seriously.

The problem? Using these years as bookends creates a tidy story but leaves out the messy, unfinished chapters of civil rights work, and many key contributors before and after.

The Long Civil Rights Movement: It’s Bigger Than That

If the 1954-1968 framework feels a bit like squeezing an elephant into a phone booth, meet Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s “Long Civil Rights Movement.”

This concept throws the spotlight backward, tracing the roots of activism and struggle back to the 1930s—and even earlier. It recognizes decades of groundwork laid by tireless activists like Ida B. Wells and W.E.B. Du Bois, and organizations like the NAACP, which fought on the front lines long before the famous marches.

Think of it as a relay race: the triumphant sprints of the ’50s and ’60s came only because generations of organizers carried the baton first.

One podcast guest on AskHistorians explained how this broader view reveals a vibrant, ongoing fight, challenging the idea that civil rights is confined to a “golden era.”

The movement also encompasses complex politics. The Communist Party’s ties to early civil rights work led to a toxic backlash branding civil rights activism as “communism” to discredit it—a historical wrinkle often overlooked in narrow views.

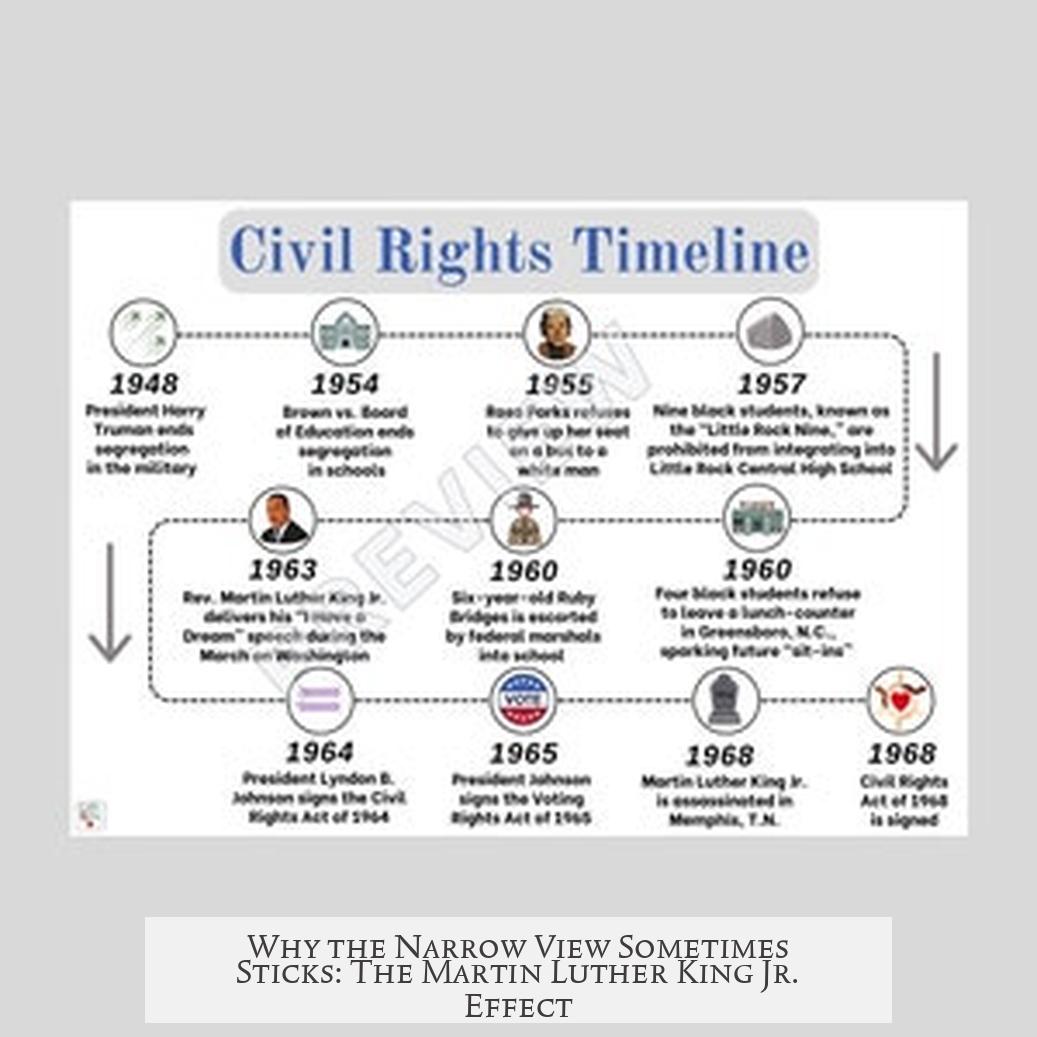

Why the Narrow View Sometimes Sticks: The Martin Luther King Jr. Effect

Part of the narrow framing comes down to one very recognizable figure: Martin Luther King Jr. His “I Have a Dream” speech at the 1963 March on Washington shines so brightly, it risks eclipsing his full legacy.

King often appears frozen in time—as the dreamer of equality during a single speech. But peel back the layers and you find a leader who connected racial justice to anti-war activism, poverty, labor rights, and even socialism.

The “friendly” version of King skips over his opposition to the Vietnam War, his critiques of segregation in the North, and his push for economic justice through the Poor People’s Campaign. It even omits his support for unions and radical change that landed him in hot water before his assassination in 1968.

This selective memory creates a neat, less controversial symbol, but misses King’s broader vision—and it conveniently avoids tough questions like reparations and inclusion of LGBTQ+ rights within civil rights frameworks.

As one sharp commentator quipped, freezing King to a single moment makes it easier to dodge those sticky topics—and keeps civil rights narrowly defined as just racial equality.

What Gets Left Out When We Pick Dates Too Narrowly?

Whose stories get lost when we stick to 1954-1968? Plenty.

- Efforts before 1954, like anti-lynching crusades led by Ida B. Wells.

- Ongoing civil rights battles after 1968, including enforcement struggles around the Fair Housing Act.

- The broader fight for equality that includes gender, sexual orientation, labor, and economic justice.

Even supporters of a limited timeframe often do so without ill intent—they might simply be unaware or overwhelmed by the complexity. But this choice shapes public memory and policy debates to this day.

Limiting the era leaves out so much impactful work and many activists who deserve recognition.

So, What’s the Takeaway?

Is the US Civil Rights Movement a defined period from 1954 to 1968? Not quite. It’s better seen as an evolving struggle that spans generations—including battles before 1954 and ongoing fights long after 1968.

By embracing this long view, we honor the full scope of activism, the intricate politics involved, and the broad range of civil rights issues. It challenges us to think critically about history and recognize that justice is rarely achieved in neat chapters.

So next time someone tries to pin down civil rights to a strict timeline, ask them: “What about the decades before Brown v. Board? What about the civil rights fights going on right now?” Because in truth, the movement is as alive today as ever.

How Can We Apply This Understanding Today?

- Support education that highlights the long history of civil rights activism—not just a few famous years.

- Recognize connections between racial justice and other social movements, such as LGBTQ+ rights and economic equality.

- Encourage conversations that include full portrayals of leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., acknowledging their radical visions.

- Stay aware that civil rights struggles aren’t “over” just because laws passed decades ago.

Understanding the Civil Rights Movement as a long, imperfect, ongoing journey helps us see that building a more just society is never a finished project. And maybe that’s the real lesson history wants to teach us.