It is partially correct to refer to the Ottomans as Turks, but the term oversimplifies the empire’s complex, multi-ethnic nature. The Ottoman Empire originated from Turkic peoples and used a Turkic language. However, its ruling class, military leaders, and population included many diverse ethnic groups over centuries, making exclusive identification as “Turks” inaccurate.

The Ottoman Empire spanned over 600 years and incorporated numerous ethnicities. Political and military leadership was notably multi-ethnic. For example, Sulayman the Magnificent’s grand vizier, Pargali Ibrahim Pasha, was Greek by origin. The influential Köprülü family, serving as grand viziers, had Albanian roots. Others linked to different backgrounds, such as Persian or Kurdish ancestry, also held high posts.

Several Ottoman sultans themselves had diverse maternal origins. Sultan Mehmet II’s mother might have been Italian or Serbian. Selim II’s mother was Polish, and Mehmet IV’s mother was Ukrainian. Many top commanders came from Balkan and European backgrounds: Bosnian, Croat, Albanian, even Italian. These ethnicities were not Turkic, nor did all speak Turkic languages.

European chroniclers often referred to the Ottoman ruling class as “Turks” and labeled the empire “Turkey.” The European public broadly used these terms during the empire’s height. Similarly, in the Muslim world, the empire was called dawlat al-‘Uthmaniyya (the Ottoman State), but the term “Turks” was also applied to them by some, such as Yemen’s Qasimi Imams.

Despite historical usage, calling all Ottomans “Turks” obscures important details. The empire was largely European in geography, especially after capturing Constantinople. Many Ottomans rejected Turkish ethnic identity, especially in later centuries. In fact, “Turk” sometimes carried negative connotations within Ottoman society, attached to rural peasants rather than the elite.

The late Ottoman elite distanced themselves from Turkishness. The word “Turk” was used disparagingly in various languages spoken by former Ottoman subjects. Evidence suggests anti-Turkism existed within the empire. For this reason, people at the time occasionally favored identifying as “Ottomans,” emphasizing political and dynastic allegiance over ethnicity.

Clear historical discussion benefits from precision. For example, attributing events like the Armenian Genocide to “the Turks” simplifies complex reality and risks ethnic stereotyping. In academic and responsible discourse, saying “the Ottomans” or “the Ottoman government” avoids unfair ethnic generalization, akin to saying “the Nazis” instead of “the Germans” for Holocaust responsibility.

Using “Turks” remains valid in specific contexts. The empire’s founders were Turkic, and the official language was Turkic. In describing military engagements like the siege of Malta, “Turks” serves as a convenient shorthand without substantial confusion. However, when ethnic identity risks being misattributed or politicized, “Ottoman” is preferable for accuracy.

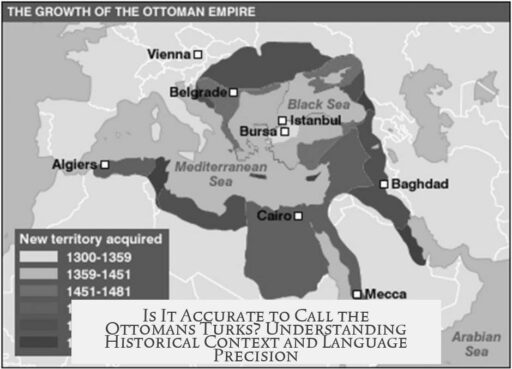

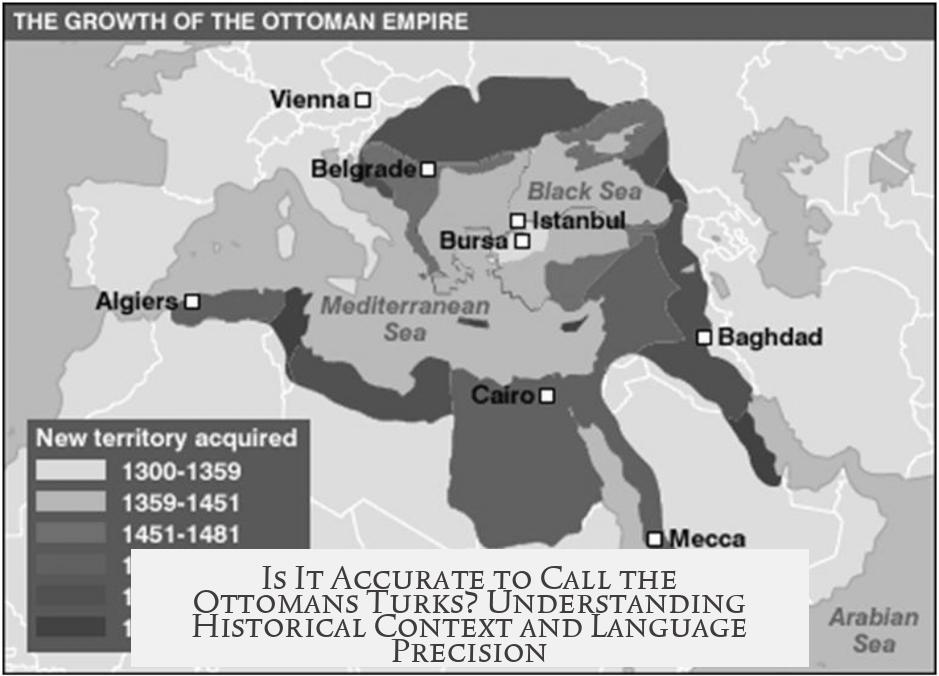

The term “Ottoman” itself derives from Osman (Ottoman Turkish “Osmanlı”), the dynasty’s founder. This highlights the empire’s dynastic nature rather than its ethnic base. The empire was not majority Muslim until the 16th century following the conquest of Cairo, further illustrating its evolving demographic character.

| Aspect | “Turk” as Term | “Ottoman” as Term |

|---|---|---|

| Ethnic Identity | Turkic origin and language | Multi-ethnic, dynastic empire |

| Political Usage | Used by Europeans broadly | Emphasizes dynasty and statehood |

| Social Context | Sometimes peasant stereotype, negative connotations | Preferred by elites, inclusive term |

| Accuracy | Oversimplifies diverse demographics | More precise, avoids ethnic misattribution |

- The Ottoman Empire was a politically and ethnically diverse state.

- Many Ottoman leaders and sultans had non-Turkish origins.

- “Turks” was a common European shorthand but not always accurate.

- Using “Ottoman” reduces ethnic stereotyping in historical discussion.

- “Turk” remains valid in limited historical contexts referencing early empire or language.

Is It Correct to Refer to Ottomans as Turks?

In short: calling the Ottomans ‘Turks’ isn’t exactly correct, though understandable—and sometimes convenient—but it misses a lot of the empire’s rich, complex diversity. The Ottoman Empire was famously a melting pot of ethnicities, cultures, and religions. So, slapping the label “Turks” on its entire population or leadership oversimplifies history and can even lead to confusion or misunderstanding.

But don’t just take my word for it—let’s dive into the why and how this mix-up happens.

The Many Faces of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire wasn’t just a Turkish story. Far from it. For over 600 years, the empire was multi-ethnic and multi-cultural. Its politics and military leadership included Armenians, Greeks, Albanians, Kurds, Bosnians, Italians, and many others.

- For example, the grand vizier under Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent was Pargali Ibrahim Pasha, of Greek origin, who was recruited through the devshirme system—that means he was taken as a child and trained for government.

- The powerful Köprülü family of grand viziers was Albanian.

- Grand vizier Karamani Mehmed Pasha traced his roots to Persian mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi, not Turkish ancestry.

- Military commanders included Bosnian Mehmet Sokollu, Croatian Sinan Pasa, Albanian Semsi Pasa, and even Italian Kilic Ali Pasa!

- Even the sultans had diverse backgrounds: Mehmet II’s mother was either Italian or Serbian; Selim II’s mother was Polish; Mehmet IV’s mother was Ukrainian.

Bottom line? Ethnicity wasn’t a defining factor of Ottoman identity for most of its existence. The empire was more about governing a vast, diverse territory united under the Ottoman dynasty than about any single ethnic group.

Why European and Muslim Worlds Used ‘Turks’ Anyway

Here’s where things get a bit murky. Europeans and many Muslim populations often used “Turks” to describe Ottoman rulers and soldiers. Think of it like a nickname that stuck.

- Europeans even called the empire “Turkey.”

- Converting to Islam was sometimes called “turning Turk” in European discourse, reflecting perceptions of Ottoman dominance.

- Some Muslim groups also referred to the Ottomans as “Turks,” such as the Qasimi Imams of Yemen.

So was this strictly accurate? No. But it was shorthand and part of the common language in historical writings and everyday speech.

Why Calling Ottomans ‘Turks’ Might Ruffle Feathers

Here’s a plot twist: not everyone within the Ottoman Empire liked being called “Turks.” Some elites, especially in later periods, found it offensive. “Turk” often carried a rural, sometimes derogatory connotation:

- The word was used disdainfully for Anatolian peasants by Ottoman elites.

- Anti-Turkism existed within the empire itself, showing that identity was more complicated than a simple label.

- Late Ottoman officials preferred the term “Ottoman,” emphasizing their dynasty and ruling class rather than an ethnic identity.

It’s a bit like calling every politician from the UK “Londoners” — technically not right and likely to annoy the Scots and Welsh!

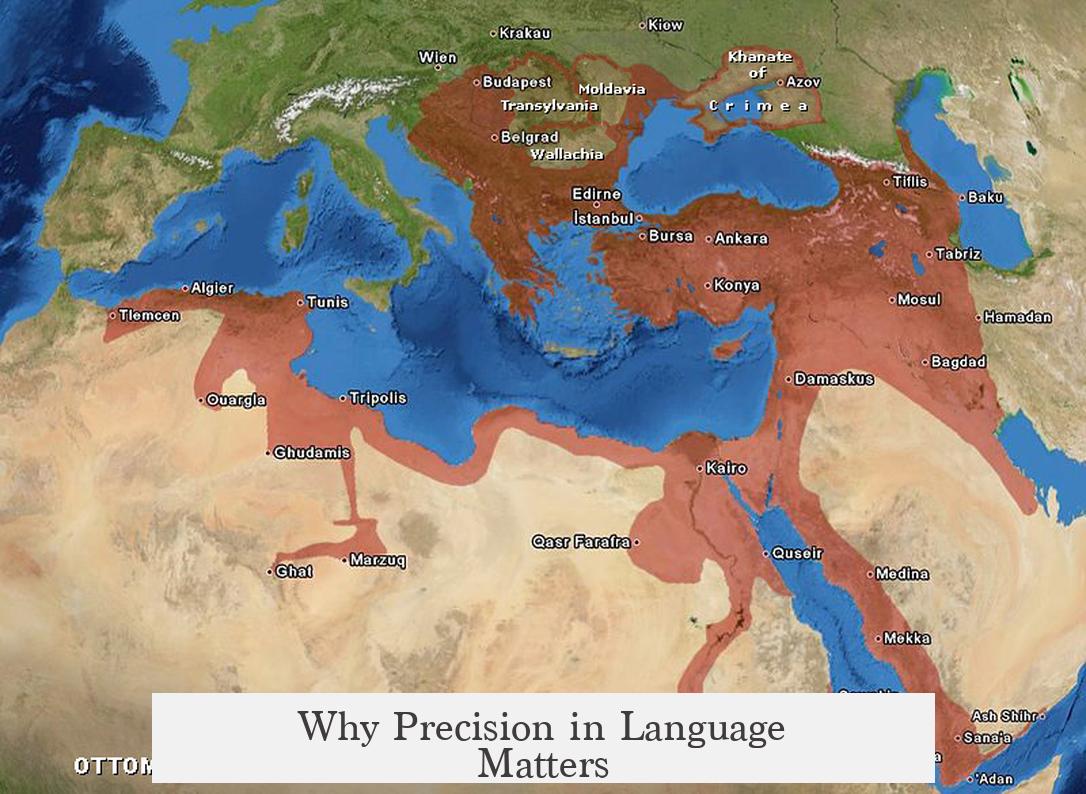

Why Precision in Language Matters

History benefits when details remain precise. Saying “Ottoman” instead of “Turk” helps avoid attribution errors:

- The Armenian Genocide, a tragic event, was carried out by the Ottoman government, not by “the Turks” as an ethnic group.

- Likewise, with the Holocaust, we say “Nazis,” not “Germans,” to prevent unfair ethnic or national blame.

- Use “Ottoman” to capture the political and dynastic reality without unfair stereotypes.

So, clarity isn’t just pedantry. It’s about fairness and accuracy.

When Calling Ottomans ‘Turks’ Works (and When It Doesn’t)

That said, there are valid reasons people call Ottomans “Turks”:

- The empire was founded by Turkic people from Anatolia.

- Its ruling language was Turkic.

- In early years, this Turkic identity was uncontroversial and clear.

- When discussing quick shorthand—for example, the siege of Malta—using “Turks” usually won’t confuse anyone.

Ultimately, if you want to avoid misleading someone about ethnicity or culpability, “Ottoman” is the safer, more respectful bet.

A Note on Language and Dynasties

The word “Ottoman” comes from “Osman,” the dynasty’s founder. It’s a European take on a Turkish name, but it highlights something important:

- The empire revolved around a ruling family, not an ethnic bloc.

- Prior to conquering Cairo in 1517, Muslims were not even the majority within the empire.

- Saying “Ottoman” focuses on political power and dynasty rather than ethnicity alone.

Think of it this way: The British Empire had rulers and subjects from everywhere but we don’t usually call all of them “English.”

What’s the Takeaway?

So, should you call Ottomans “Turks”? If you want to capture the empire’s early Turkic roots or speak informally, it’s understandable. But historians and curious minds should reach for “Ottoman” to respect the empire’s ethnic diversity and complex history. This approach prevents stereotypes and helps us appreciate one of history’s most fascinating empires in all its multi-ethnic glory.

Does this change how you picture the Ottomans? Instead of a single “Turkish” identity, imagine a vibrant empire where Greeks, Albanians, Slavs, Kurds, and Italians all helped shape events. Quite a different story than the simplified headlines.

Next time you hear “the Turks” in history class or in a book, ask yourself: “Are we really talking about an ethnic group, or an empire built from many different peoples united under one remarkable dynasty?” That question alone makes history richer and more interesting.