Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Anne Applebaum offer different perspectives on the Gulag system, with varying degrees of reliability. Solzhenitsyn, a literary figure and former prisoner, provides powerful personal testimony but lacks historical rigor and exaggerates figures. Applebaum, a journalist, offers a well-researched, archival-based history accepted by scholars, albeit with some ideological bias.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn is not a professional historian. His works focus on personal experience and literary narrative rather than comprehensive historical analysis. His major contribution, The Gulag Archipelago, opened Western eyes to the Soviet forced labor camp system during the Cold War. However, the book relied on limited and sometimes dubious sources. At the time, Soviet archival materials were inaccessible, forcing Solzhenitsyn to depend on eyewitness accounts and émigré statistics, which led to inflated death toll estimates—such as his claim of 66 million deaths, a figure widely discredited by contemporary historians.

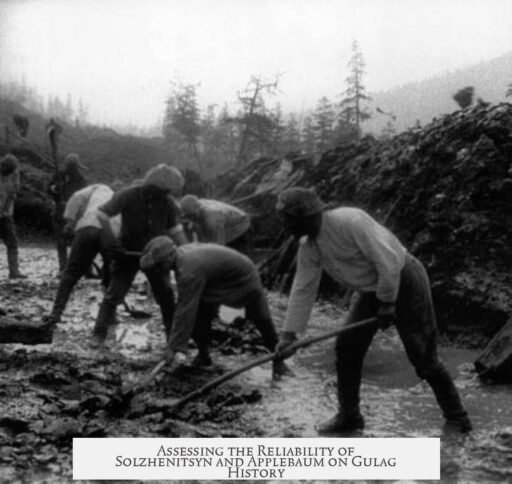

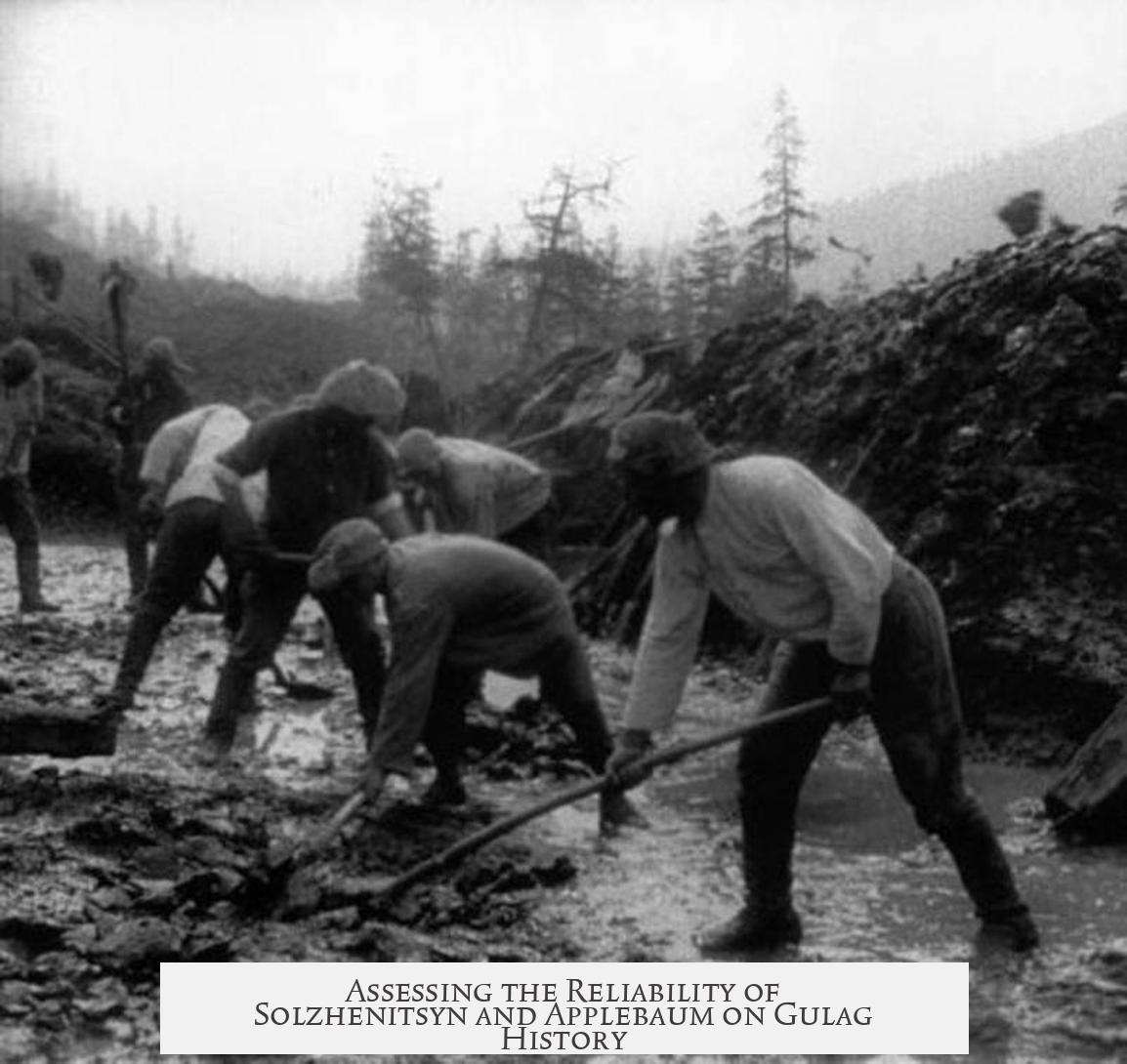

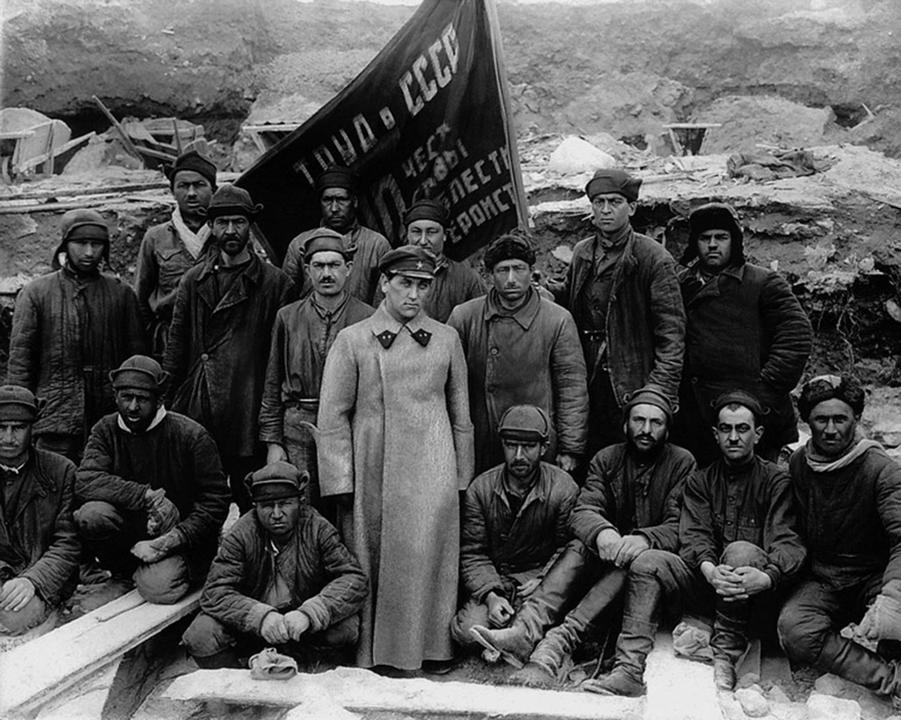

Solzhenitsyn’s narrative power lies in its vivid depiction of camp life. Works like A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich remain among the most effective literary portrayals of prisoner experiences. Yet, the historical data he presents contain notable inaccuracies. For instance, he drew on Ivan Kurganov, an émigré statistician with Nazi collaboration ties, which undermines the reliability of some of his claims. While Solzhenitsyn’s accounts shaped Western understanding of Soviet repression, they serve best as personal testimony rather than academic history.

Anne Applebaum’s Gulag: A History differs fundamentally in approach. Writing after the Soviet archives opened, she utilizes official documents alongside survivor testimonies to present a more evidence-based history. Her work is a standard text in the field and the demographic and operational data she provides align well with scholarly consensus.

Applebaum’s ideological standpoint is clearly anti-communist. She frames the USSR and Nazi Germany as parallel totalitarian regimes, a viewpoint somewhat out of favor among modern historians who emphasize nuance and differences. Nevertheless, her analysis does not let ideology overwhelm fact. Her book is rigorous in documenting the gulag’s brutality and systemic indifference. Critics note that her introduction and conclusion have a polemical tone, but her core scholarship remains strong. For readers seeking a comprehensive yet accessible history, Applebaum is highly recommended.

Academic consensus estimates about 1.5 million deaths in the Gulag system during the Soviet era. This figure contrasts sharply with Solzhenitsyn’s exaggerated claims but aligns with Applebaum and other historians, including Timothy Snyder. Many prisoners died outside camps after release due to mistreatment, which complicates exact mortality counts. The majority of inmates survived their sentences, but endured harsh conditions, persistent sexual violence, and imprisonment often without legitimate cause.

Modern historians like Oleg Khlevniuk provide a more sober, archival-focused view of the gulag that surpasses both Solzhenitsyn and Applebaum in academic detail. Khlevniuk’s works, while dense, offer updated information less influenced by ideological frameworks.

It is important to reject revisionist claims that trivialize the gulag’s cruelty or equate it simplistically with Western prison systems. Such arguments often rely on weak sources and ignore the unique systemic function of the Soviet forced labor camps.

| Historian | Strengths | Weaknesses | Reliability Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander Solzhenitsyn | Powerful literary depictions; firsthand experiences; influential Cold War perspective | Non-historian; outdated; exaggerated figures; questionable sources | Valuable personal witness but unreliable for precise historical data |

| Anne Applebaum | Archival research; well-accepted figures; broadly reliable narrative | Ideological bias; polemical framing in intro/conclusion | Standard, reputable academic work recommended for general history |

| Modern Scholarship | Access to archives; accurate data; deeper contextual analysis | Sometimes overly technical or dry | Most reliable source for detailed historical facts |

Readers should approach Solzhenitsyn as a foundational literary and cultural source rather than a strictly factual account. Applebaum’s work is better suited for gaining a broad historical understanding, but those seeking academic depth should consult additional scholarly works. Both contribute importantly to the conversation about the Soviet gulag system, but with different methodologies and limitations.

- Solzhenitsyn offers powerful personal insight, not precise historical data.

- Applebaum’s archival research forms a credible academic foundation despite some ideological framing.

- Modern historians with archival access provide the most accurate and updated figures.

- The gulag mortality is around 1.5 million deaths, lower than Solzhenitsyn’s claims but backed by archival evidence.

- Revisionist comparisons minimizing the Gulag’s uniqueness lack scholarly credibility.

How Reliable Are Solzhenitsyn and Applebaum Regarding the Gulags?

If you’re diving into the shadowy world of the Soviet Gulags, you might ask: how reliable are Alexander Solzhenitsyn and Anne Applebaum when it comes to their accounts of these brutal forced labor camps? Both names pop up often, but their approaches, strengths, and flaws differ considerably. So let’s unwrap the layers and get to the heart of their reliability.

Anne Applebaum: Scholarly, But with a Side of Ideology

Anne Applebaum is no stranger to controversy. She worked for conservative outlets like The Economist and wears her anti-communist stance on her sleeve. She tends to lump the USSR and Nazi Germany firmly into the “totalitarian regimes” box, a view that’s somewhat out of vogue among modern historians. Yet, despite this ideological coloring, her Gulag: A History is widely recognized as a solid piece of scholarship.

Why is her work respected? It’s because she had access to the post-Soviet archives, shedding light on official documents long hidden from the world. The figures she cites about the Gulag system have gained traction among serious Soviet historians. No one’s lined up to throw tomatoes at her when it comes to those numbers.

Applebaum’s narrative doesn’t sugarcoat the Gulags’ horrors—far from it. She describes brutality and indifferent cruelty straight-up, which admittedly makes for grim reading but offers authenticity. Her book isn’t perfect—her intro and closing chapters sometimes come off as polemics rather than dispassionate history—but it remains a recommended starting point for anyone serious about the subject.

If you want a more laser-focused, academic text, consider Oleg Khlevniuk’s The History of the Gulag: From Collectivization to the Great Terror. It’s drier, sure, but a veritable goldmine for historians hungry for detail.

Alexander Solzhenitsyn: Literary Giant, Not a Historian

Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s name is almost synonymous with the Gulag in Western discourse. His writing humanizes the prisoners’ suffering in ways numbers cannot. A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich is a literary classic, masterful in showing one man’s daily grind inside the camps.

But here’s the catch: Solzhenitsyn is emphatically NOT a historian. He didn’t base his accounts on archival research or verified data. Instead, he relied on personal experience and some shaky secondary sources—back when accurate information was nearly impossible to get in the West.

His landmark book, The Gulag Archipelago, shook the world when it was published abroad. It embarrassed the USSR and exposed Western readers to a chilling view of Soviet repression. Yet today, it’s a bit of a time capsule—more relevant historically than factually precise.

His mortality figures raise eyebrows. In one interview, he claimed 66 million deaths in the camps—more than the entire population of the USSR at that time! This number clashes starkly with modern estimates of roughly 1.5 million deaths in the Gulags themselves. Moreover, Solzhenitsyn used data from Ivan Kurganov, a Russian émigré statistician with a Nazi collaboration past, which seriously weakens his credibility. Even other émigrés disapproved of citing Kurganov.

Despite these issues, Solzhenitsyn’s accounts are invaluable for understanding Cold War-era perceptions in the West. His vivid experiences shed light on the human condition under Soviet repression—just don’t treat his books as cold, hard history.

Bridging the Gap: Where Do They Agree and Clash with Modern Historians?

One quick comparison reveals big differences in methodology:

- Solzhenitsyn: Personal narrative and questionable sources, no access to documents.

- Applebaum: Archival research with well-accepted historical figures.

When it comes to death tolls, Solzhenitsyn’s staggering figures contradict the scholarly consensus. Historians agree that about 1.5 million died in the camps themselves, with more perishing outside because the system “released” dying inmates to avoid counting them as camp deaths. Timothy Snyder, a respected historian, confirms these figures and finds no dispute.

Both agree on the nature of the Gulags as places of unimaginable suffering, though not as death camps like Nazi extermination centers. Many inmates survived but bore lasting scars. Sexual violence was rampant, and countless people were arrested for trivial or political reasons, simply for who they were.

Beware of Revisionist or Propaganda-Laden Objections

Some modern rebuttals try to downplay the Gulags by comparing them to American prisons or denying their horrors. These often rely on weak sources like YouTube channels and ignore the unique brutality of Soviet forced labor.

It’s essential to recognize that Gulags weren’t just prisons—they were part of a system of political repression and forced labor with distinct aims and horrors. Comparing them wrongly clouds the historical truth.

Summing Up the Reliability Scorecard

| Historian | Strengths | Weaknesses | Reliability Summary |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alexander Solzhenitsyn |

|

|

Valuable for understanding the lived experience and Cold War Western perspective but not a reliable historical source. |

| Anne Applebaum |

|

|

Standard and reputable academic work; recommended with awareness of some ideological bias. |

| Modern Scholarship |

|

|

Most reliable and nuanced source for understanding Gulag history and statistics. |

Why Does This Matter to You?

Ever wondered how historical narratives shape modern politics? Understanding the nuances of reliability helps avoid walking into ideological traps. Should you trust the evocative stories of Solzhenitsyn or the archival rigor of Applebaum? Both! But remember their limitations.

For instance, reading A Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich gives you a gritty, personal glimpse into camp life. But if you’re writing a paper on Soviet repression, you’ll want Applebaum’s researched and referenced material or even the more academic Khlevniuk.

In today’s era, where misinformation thrives, knowing the difference between testimony, ideology, and archival history is a superpower. The gulags were horrific, but the truth deserves to be more than just emotionally charged rhetoric or ideological storytelling.

Final Thoughts: Solutions for the Curious Reader

- Start with Applebaum’s Gulag: A History for a clear, accessible overview backed by archives.

- Supplement with Solzhenitsyn’s narratives to understand personal experiences and Cold War era perceptions.

- Dig deeper with Oleg Khlevniuk’s work for a scholarly deep dive.

- Keep a critical eye on figures and claims—if a death toll sounds monstrous (like 66 million), ask “Where’s the evidence?”

- Avoid sources that over-politicize or undermine the unique horrors of the Gulag.

So, how reliable are Solzhenitsyn and Applebaum on the Gulags? Solzhenitsyn delivers compelling narratives but shaky data; Applebaum offers a credible, archival-based history colored by ideological framing. Both remain crucial voices—just remember to read them with your historian’s hat firmly on.