Ireland became heavily dependent on potatoes—a crop introduced from the New World—because of its poor land, economic pressures under British rule, and the nutritional advantages the potato offered. This unique combination made the Irish population reliant on potatoes, which ultimately led to the calamity of the potato famine.

Poor soil conditions and hilly terrain limited Ireland’s ability to grow traditional grain crops like wheat or barley. Much land was used for grazing rather than intensive agriculture, resulting in low food yields. Under British control, most fertile land was owned by English landlords. They focused on growing cash crops and exporting food to England, leaving Irish tenants with marginal lands unsuitable for major crops.

Potatoes arrived in Ireland in the late 16th century. Their resilience allowed growth on poor soils and in harsh climates where other crops failed. They provided more calories per acre than grains and required less labor and inputs. This suited the Irish peasants, who had little access to land and few resources. Potatoes became the primary source of calories because they were cheap, productive, and highly nutritious compared to cereals.

This shift supported dramatic population growth. More people could survive on small plots due to the potato’s efficiency. However, the land remained controlled by landlords who emphasized export of other crops. Large quantities of wheat and livestock products continued being shipped out of Ireland, leaving the local population dependent on their potato crop for survival.

When the potato blight struck in the 1840s, the failure of this staple crop devastated millions. Ireland had insufficient food reserves or alternatives due to export policies and poverty. British government responses exacerbated the crisis by allowing food exports to continue despite widespread starvation. The combination of fragile land use, economic exploitation, and dietary dependence on a single crop caused the famine’s severe human toll.

- Irish soil and climate limited traditional crops, favoring hardier potatoes.

- English landlords prioritized cash crops and export profits over local food needs.

- Potatoes offered high nutrition and yield on tiny plots, supporting population growth.

- Ongoing export of other foodstuffs intensified local reliance on potatoes.

- Famine disaster arose from this mono-crop dependence and inadequate relief efforts.

How Did Ireland Become So Dependent on Potatoes, a New World Plant, That the Potato Famine Was Possible?

Simply put, Ireland’s love affair with the potato was born out of necessity, land politics, and economic policies that favored English profits over Irish survival. How did a plant unknown to Europe until the Columbian Exchange—potatoes—become the backbone of Irish sustenance and, tragically, the cause of mass starvation? Let’s unpack this complex historical dish.

The Irish Land Dilemma: A Ground Zero for Dependence

First, picture Ireland’s landscape: mostly poor soil, not made for bountiful harvests of traditional grains like wheat or barley. Grazing dominated the land use, but animals, unlike crops, convert a lot of feed into relatively little food. Not exactly an efficient food factory.

Now toss in the fact that much of the arable farmland was under British ownership, held by English nobles who prioritized cash crops for export over feeding the local Irish populace. This meant the “good” land didn’t feed Irish families—it supplied British markets.

Amazing, isn’t it? Even when hunger struck Ireland, food exports continued, shipments of wheat and other grains sailed across the sea, leaving the local population with scraps. The land was locked in a brutal economic hierarchy: food grown for profit, not people.

Potato Arrival: Nature’s Unlikely Savior

Enter the potato, the botanical equivalent of the surprise hero arriving in the nick of time. Native to the New World and unknown to Europe before the late 16th century, potatoes thrived in Ireland’s poor soil and cool, wet climate where cereal crops failed.

Why potatoes? Because they were nutrient-rich, calorie-dense, and cheap to grow—no fancy farming degrees required. They could sustain a population that other crops simply could not support, making them the perfect food for the land-poor and cash-poor Irish peasants.

This wasn’t just about hunger; it was about survival and growth. The population skyrocketed because potato harvests were reliable and hearty, giving life to more than just small families—it fueled entire communities and rural economies.

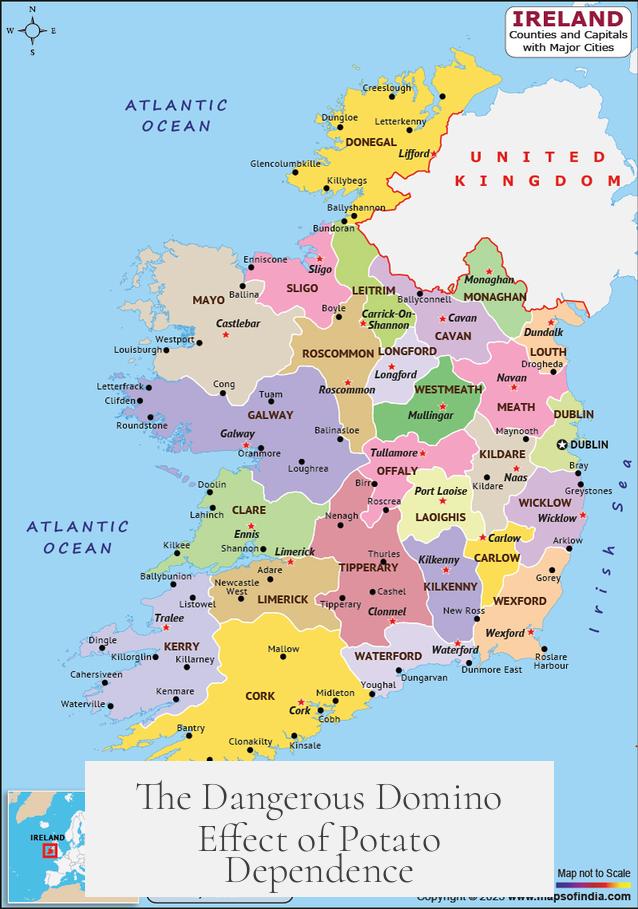

The Dangerous Domino Effect of Potato Dependence

Here lies the twist with tragic consequences. Ireland’s dependence on a single food crop—potatoes—created a fragile system. When the dreaded Potato Blight struck in the 1840s, wiping out the crops, millions suddenly faced starvation.

Why no backup? Because the other food sources were literally exported away, prioritized to feed British citizens or merchants instead of the Irish peasantry. Wheat, barley, and oats were shipped out, leaving almost no local reserves to fall back on.

To add insult to injury, the British government’s poor handling of the crisis—continuing food exports during an acute famine—exacerbated the tragedy. Policies failed to provide relief, and millions perished or emigrated.

The Broader Picture: Politics, Economics, and Agriculture Intertwined

- The core land holdings were English-owned, with a focus on maximizing cash crops and exports.

- Irish peasants lived mostly on marginal lands unsuitable for wheat but perfect for potatoes.

- Potato’s energy density and ease of growth made it an ideal—but risky—primary food source.

- Export-first policies stripped local food security, pushing Irish dependence on the tuber.

- This fragile monoculture meant that when potatoes failed, the system collapsed.

What Can We Learn From This Episode?

Here’s a powerful lesson wrapped in history: depending heavily on a single food source—no matter how nutritious—can be disastrous if not backed up by diverse and sustainable agriculture. Economic policies that prioritize profits over people can amplify this risk.

Imagine if more Irish farmland were devoted to local food crops instead of exports? Or if policies had protected food reserves during crises? The famine’s impact might have lessened dramatically.

Today, this story nudges us to think about food security, diversity in agriculture, and political responsibility. How can we avoid repeating history’s mistakes when it comes to feeding populations sustainably?

Final Thoughts

The story behind Ireland’s potato dependence is a tale of geography, economics, and colonial politics converging in an unfortunate dance. Potatoes transformed Irish survival, allowing populations to grow in difficult conditions. But reliance on this “miracle crop,” combined with exploitative export policies, set the stage for one of the most devastating famines in history.

So, while the potato came from the New World and brought hope, it also became a symbol of vulnerability. A sobering reminder that food systems and policies must balance nutrition, economics, and fairness to truly sustain life.

“The Irish Potato Famine teaches us that when survival hangs on one thread, the whole fabric can unravel—fast.”

Next time you bite into a potato, think about this journey—from a humble tuber to a lifeline and a lesson carved deep into history.