The stereotypical French maid outfit becomes a fetish in the West through its roots in 19th-century French theatre and society, and later evolves into a staple of Japanese Lolita fashion by reinterpreting Victorian and youthful aesthetics within a culturally distinct subculture starting in the 1970s.

The French maid costume, known in French as the costume de soubrette, originates from the theatrical soubrette character—a vivacious, often flirtatious maid figure in comedic plays. This character demands an appearance combining youthfulness and sexual openness, in contrast to modest mistresses. The soubrette’s costume highlights cleavage and incorporates playful, provocative elements, reflecting its fictional and performative nature rather than genuine domestic attire.

In 19th-century France, the boundary between actresses—who frequently performed soubrette roles—and courtesans was very thin. Actresses often supplemented their income through sex work, linking the soubrette costume to erotic and sexualized connotations early on. Simultaneously, real maids often faced exploitation, sexual violence, and social judgment as both victims and temptresses. This complex stereotype, reinforced in literature and popular culture, depicted maids as both corrupted and corrupting figures. Writers like Gustave Flaubert and Guy de Maupassant portrayed maids as objects of desire and symbolic of seduction, cementing the costume’s association with erotic fantasy.

These cultural narratives laid the foundation for the French maid outfit’s incorporation into Western fetish culture. Although specific dates and mechanisms of the costume’s fetishization are not exhaustively detailed, the eroticized theatrical and social imagery of the soubrette and maid roles throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries foster these associations. Over time, the black-and-white maid costume with its lace accents, short skirts, and aprons became a recognizable fetish outfit in Western adult entertainment and popular culture.

Meanwhile, in Japan, a different cultural journey shapes fashion inspired in part by Western Victorian and Edwardian dress. From the Meiji period onward, Japanese society experiences modernization and increased female education. This supports new self-expression via shoujo (young girl) magazines and media, especially from the 1970s and 1980s during the post-war economic boom. Various subcultures arise, including gyaru, yankee, and notably Lolita fashion within the kawaii (cute) aesthetic.

Japanese Lolita fashion draws heavily on Victorian doll-like clothing, spurred by the visual-kei rock music scene’s elaborate style. It embraces lace, frills, and bonnets, emphasizing modesty, elegance, and youthfulness. Notably, Lolita fashion rejects the Western sexualization typically linked with similar attire. The culture distances itself from the eroticized gaze by emphasizing qualities like politeness, grace, and innocence—an intentional counter to the defiling image popularized by Western media such as Nabokov’s Lolita.

Within Lolita culture, the maid outfit appears as part of this broader aesthetic but is framed as empowering rather than fetishistic. The costume is worn in ritualized social spaces where participants celebrate a self-defined identity outside mainstream norms. Displayed manners, specific speech patterns, and a dismissal of vulgarity reinforce its separation from mere cosplay or sexual roleplay. This careful cultural reinterpretation transforms the maid outfit into a symbol of refined youthfulness and self-expression in Japan.

| Context | Western French Maid Fetish | Japanese Lolita Maid Style |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Theatrical soubrette and maid stereotypes from 19th-century France | Victorian/Edwardian doll aesthetic mixed with kawaii shoujo subculture since 1970s |

| Connotation | Sexualized, erotic, connected to servant-master power dynamics | Modesty, innocence, politeness, youthfulness |

| Social Role | Erotic fantasy and fetish wear in adult entertainment | Empowering self-expression, social ritual, cultural identity |

| Relation to Sexualization | Overt erotic and fetish appeal | Explicit rejection of sexual objectification |

The French maid costume’s journey into Western fetishism reflects historical social attitudes about servitude and female sexuality. Meanwhile, its adoption into Japanese Lolita fashion highlights cross-cultural adaptation that reshapes garments within new meanings. This contrast illustrates how fashion items can embody widely differing cultural values and symbolic functions.

- The French maid outfit stems from the 19th-century French theatrical soubrette, known for playful and sexualized attributes.

- Cultural stereotypes of maids involved exploitation and erotic fantasies, fueling the costume’s fetish status in the West.

- The exact timeline of the maid costume’s fetishization remains uncertain but is grounded in longstanding theatrical and social tropes.

- Japanese Lolita fashion developed from the 1970s as a youthful, modest style inspired by Victorian dress and kawaii culture.

- In Japan, the maid outfit becomes non-sexualized, symbolizing politeness and empowerment within social performance.

- The two traditions reflect divergent cultural relations to sexuality, youth, and female representation.

How and when did the stereotypical French maid outfit become a fetish in the West and a staple of Lolita fashion in Japan?

The stereotypical French maid outfit evolved as a fetish in the West largely through its theatrical and social roots dating back to 19th century France, where the soubrette character—an attractive, witty maid—was both eroticized and fictionalized. Simultaneously, in Japan, the style was adapted into the Lolita fashion scene starting in the late 20th century, where it transformed into a symbol of youthfulness and modesty rather than sexualization. These two trajectories, while sharing superficial costume elements, diverge sharply in cultural meaning and origins.

Let’s unravel this fascinating sartorial journey.

The French Soubrette: Fictional Origins Meet Real-life Complexity

In France, the term for the French maid costume is costume de soubrette. This label immediately signals fiction, not authentic domestic worker attire. The soubrette was a theatre stock character, popular in comedies since the 17th and 18th centuries. She’s often portrayed as a lively, outspoken, and cheeky maid—think witty, young, and sexy sans the modern ruffled apron or tiny feather duster.

The soubrette, according to Larousse’s 1875 Dictionnaire universel, needed to be “young” and “attractive,” with a sexual frankness that contrasted sharply with her mistress’s modesty. Her vivaciousness and sexual openness were part of the character’s charm.

Interestingly, the iconic French maid outfit we recognize today—the short black dress, frilly white apron, lace headpiece—does not appear in these early theatrical depictions. Instead, stage texts like Molière’s Tartuffe indicate clashing with modesty was part of the soubrette’s role, hinting at cleavage or flirtatious attire, but not this particular uniform.

Between Curtain and Reality: Actresses, Courtesans, and Maids

Here’s where things get juicy. The lines between actresses playing soubrettes and courtesans were blurry in 19th century France. Female stage performers often doubled as sex workers, at least from the public’s perception. The social stigma surrounding these roles was intense, yet it didn’t diminish their erotic allure.

“Until the early 1900s, for the public, the distinction between actresses and courtesans was paper thin,” writes historian Anne Martin-Fugier. The soubrette part could be a prestigious or an entry-level role but was always tinged with sexual connotations.

Meanwhile, actual maids lived a less glamorous reality. Most were young rural immigrants entering service in urban homes. Their lives were often fraught with sexual exploitation, diseases, unwanted pregnancies, and precarious social standings.

Martin-Fugier explains: “This situation led to a duo of conflicting stereotypes: the maid was both sexual victim and a temptress.” Maids were imagined to be “naturally more sexual and promiscuous,” a damaging cliché that ignored the harsh truth of exploitation.

The imagery of maids—both real and imagined—became fertile ground for erotic fantasies. Writers and playwrights exploited these tensions in their works. For example, Guy de Maupassant’s short story Un fils depicts a maid who resists sexual assault yet later consents, highlighting society’s disturbing tendency to blame and eroticize the victim while excusing the aggressor.

How the French Maid Outfit Became a Western Fetish Symbol

The stereotypical French maid as a fetish formed slowly, building on these theatrical and societal roots. As performances, literature, and early erotica blurred reality and fantasy, the maid figure was distilled into an erotic image—a willing, cheeky servant in a distinct outfit signaling submission combined with coquettish charm.

The 19th and early 20th centuries saw burlesque and pin-up cultures resurrect and popularize this image, emphasizing the costume’s flirtatious and sexual appeal. The ruffled apron became shorthand for “naughty but nice,” turning servant attire into a playful fantasy.

Although direct historical pinpointing is elusive, by mid-20th century, the French maid outfit had cemented its place as fetish wear in Western pop culture: movies, magazines, Halloween costumes, and adult entertainment featuring the signature black-and-white dress.

Notably, the costume veers far from historical accuracy. It’s less about realism and more about conjuring a fantasy fueled by class dynamics, sexual power play, and theatrical tradition. The maid’s role as both servile and seductive nods to layered social taboos and desires.

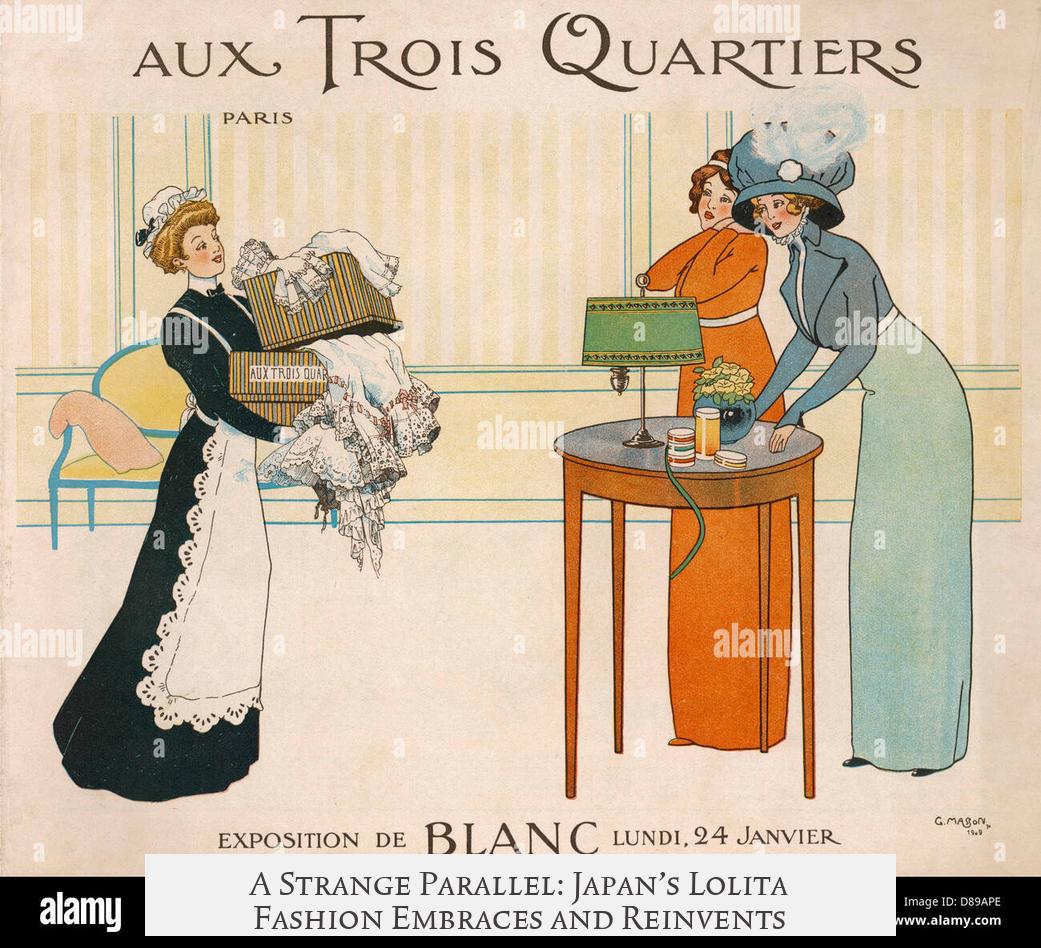

A Strange Parallel: Japan’s Lolita Fashion Embraces and Reinvents

Jump continents and decades. Japanese Lolita fashion, beginning in the 1970s–80s, absorbed Victorian and Rococo styles and, interestingly, some of the “French maid” costume elements. Here, the outfit’s adoption isn’t for eroticism but for expressing innocence, youth, and empowerment.

Japan’s rapid modernization since the Meiji era encouraged new forms of feminine expression. Shoujo magazines and comics offered a cultural playground where young women could explore identities beyond traditional expectations.

The Lolita movement emerged partly in reaction to male-dominated societal norms. It embraced cuteness (kawaii) and elaborate dress codes, channeling a princess-like fantasy with high waistlines, full skirts, lace, and modesty. French maid elements, such as ruffled aprons and bows, fit nicely into this aesthetic.

The Gothic/Lolita style draws from the visual-kei rock scene, with influences from Victorian and Edwardian aristocratic fashion. Women adopt these looks to identify as sophisticated “princesses” rather than subjugated “maids.”

Lolita fashion differentiates itself sharply from Western fetishization of maids. It rejects overt sexualization. Instead, it emphasizes grace, politeness, and ritualized performances of femininity—in language, behavior, and dress.

As scholar Isaac Gagné observes, “Lolita is meant to be empowering and strengthening… rejecting being reduced to a sexualized object and body.” Many Lolitas find frustration with cosplay cultures that sexualize their style, asserting their identity is authentic, not imitation.

Comparing Two Worlds: Fetish vs. Fashion

How strange these two evolutions are! In the West, the French maid uniform symbolizes a cheeky, somewhat transgressive sexual fantasy born from exploitative social realities and theatrical stereotypes. In Japan, similar costume elements enter a deeply different cultural conversation about youth, resistance, and identity.

| Aspect | Western French Maid Fetish | Japanese Lolita Fashion |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | 19th-century French theatre + societal stereotypes | Late 20th-century Japan, Meiji modernization + youth subcultures |

| Main Meaning | Eroticism, submission, servitude fantasy | Innocence, modesty, empowerment |

| Costume Features | Black dress, white frills, short skirt, apron | Ruffles, bows, modest skirts, Victorian-influenced |

| Social Role | Sexualized maid stereotype | Resistance to sexual objectification |

| Cultural Context | Class tensions, erotic fantasy | Subculture expression, youthful rebellion |

Practical Thoughts: What Can We Learn Here?

If you’re intrigued by the French maid outfit, remember it’s not a straightforward “historical costume.” Instead, it’s a layered symbol with roots in theatre, fraught social realities, and cinematic fantasy.

- If you want to appreciate the costume beyond fetishism, explore French theatre history, the complex social position of domestic workers, and 19th-century literature.

- For fans of the Japanese Lolita scene, understand it as a subculture with rich ritual and philosophy—not just a cute dress code.

- Recognize how fashion can carry extremely different meanings across cultures and times, shaped by social realities and collective imagination.

Next time you see a French maid outfit or Lolita dress, whether at a party, convention, or in a fashion magazine, you might smile with a bit more understanding. Behind the lace and ruffles lies a centuries-spanning story of theater, class, empowerment, and fantasy.

And hey, who knew a simple apron could carry so much weight?