The relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu in The Epic of Gilgamesh is often viewed by modern laypeople as romantically charged; historians and scholars, however, approach this with more nuance and caution. Many acknowledge a potential homoerotic element, but also emphasize the complexities of cultural context and linguistic interpretation that shape our understanding of the bond.

From a scholarly perspective, several experts have explored the idea that the Gilgamesh-Enkidu relationship carries homoerotic undertones. Starting with Assyriologist Thorkild Jacobsen in the 1930s and continuing with more recent scholars like Jerrold Cooper, some readings suggest sexual implications in specific episodes within the epic. For example, scholars analyze the “pukku and mekku” game and consider the early oppression of Uruk to have layers of sexual symbolism. The dream sequences involving Gilgamesh and Enkidu also contain wordplay that may hint at an intimate, possibly homoerotic, connection. Phrases such as Enkidu being “like a wife” or imagery comparing him to an axe have invited interpretations regarding complex sexual identities in ancient Mesopotamian texts.

Despite these interpretations, the theory remains debated. Some scholars caution against over-literal readings, especially given the layered puns and double meanings typical of ancient literature. The homoerotic dimension is considered legitimate but not definitive; it depends on how one decodes certain language nuances. This debate reflects broader challenges in interpreting ancient relationships through modern lenses.

Cultural and historical contexts play a critical role in understanding such relationships. In many ancient societies, male bonds were expressed in ways that today may appear intimate or sexual but were culturally normative. Strong emotional attachments between men did not necessarily carry the same connotations as modern romantic relationships. For instance, the biblical bond between David and Jonathan is similarly described in deeply loving terms without being understood as homosexual by most scholars. This difference highlights the risk of anachronistic assumptions when judging ancient texts by current Western social standards.

Regarding homosexuality, ancient Mesopotamia had a complex and somewhat open attitude compared to biblical Israel. Documentation includes references to homosexual prostitutes and male lovers, generally without harsh judgment. However, legal records occasionally punish the passive sexual partner, reflecting societal taboos about “going against nature.” This parallels attitudes in medieval Europe, demonstrating that certain social norms about sexual roles transcended time and location.

It is important to note limitations in the historical record. The Epic of Gilgamesh originates from early Mesopotamian history, around 3000 BCE, a time for which surviving texts and cultural knowledge are scant. Much of what we know about Mesopotamian attitudes toward sexuality comes from later periods, post-2500 BCE. The lack of direct evidence from the Sumerian era limits certainty about how exactly Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s relationship would have been understood by their contemporaries.

In comparison to other ancient cultures, male relationships could embody deep love without exclusive sexual implications. In Ancient Greece and Rome, homosexual activity was socially structured around the active/passive sexual roles, with stigma focusing on the passive role. Similarly, Mesopotamian attitudes varied by social status and sexual function. Engaging sexually with a citizen man in the passive role was taboo, but relations involving slaves or prostitutes were treated differently. This suggests ancient Mesopotamian sexual norms were socially stratified rather than strictly defined by the act itself.

Historians and scholars recognize a complex interplay of friendship, intimacy, and possible homoeroticism in Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s relationship. Modern interpretations of romance are informed by linguistic, cultural, and legal nuances that caution against simple labels.

- The Gilgamesh-Enkidu bond may contain homoerotic elements, supported by specific textual cues analyzed by some scholars.

- Interpretations are debated and heavily depend on context and translation accuracy of ancient wordplay.

- Ancient cultural norms accepted close male bonds that could seem intimate but were not romantic in a modern sense.

- Mesopotamian society showed complex attitudes toward homosexuality, focusing on sexual roles and social status.

- Limitations in the historical record, especially from early Mesopotamia, restrict definitive conclusions about the nature of the relationship.

Is the Relationship Between Gilgamesh and Enkidu Romantic? What Historians Say

From a layman’s perspective, the relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu in The Epic of Gilgamesh seems kind of romantic. Two heroic figures, inseparable companions who share deep bonds, intense emotions, and even poetic language that flirts with tender imagery—it’s understandable why many modern readers get romantic vibes. But what do historians really think? Is this ancient tale a straight-up bromance or a coded love story? Let’s deep dive.

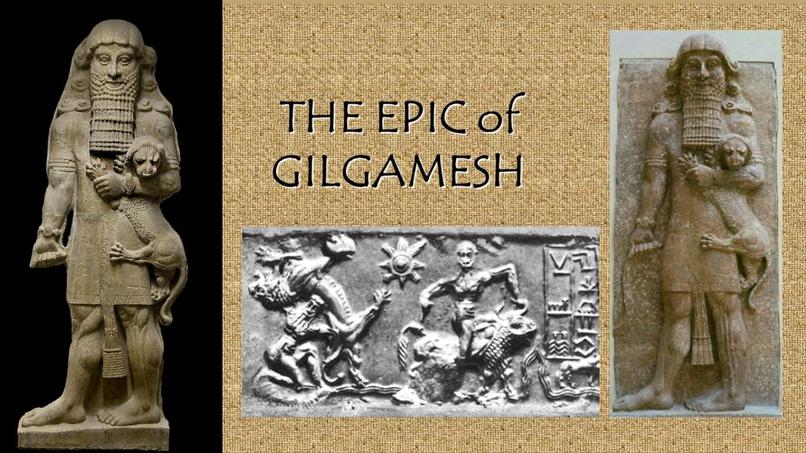

The Epic of Gilgamesh, one of the oldest surviving literary works, describes the friendship of the legendary king Gilgamesh and the wild man Enkidu. They travel, fight, and suffer losses side by side. This relationship stands out in ancient literature as fiercely loyal and emotional.

Scholars Dive Into the Text: Homoerotic Hints or Just Strong Friendship?

Since the 1930s, specialists like Thorkild Jacobsen kicked off scholarly debates by suggesting a homoerotic dimension to Gilgamesh and Enkidu’s bond. Today, Jerrold Cooper is a prominent figure advancing this reading. They base their conclusions on detailed textual analysis of the surviving versions of the poems—the Standard Babylonian, Old Babylonian fragments, and the even older Sumerian poems.

What fuels this interpretation? Some compelling clues come from wordplays and metaphors hidden in the original Akkadian language. For example, scenes involving the pukku and mekku game—terms that scholars argue might symbolically mean “ball” and “shaft”—carry sexual connotations that modern readers pick up on. Gilgamesh’s dreams about Enkidu use images such as Enkidu being “like a wife” or an “axe,” phrases suggesting layered meanings tied to sexuality and intimacy.

Despite the juicy hints, not all experts buy this reading. Some argue that these phrases might be poetic, symbolic, or ritualistic rather than outright homoerotic. The debate hinges on how literally one takes certain puns and word choices. Verdict? This interpretation is legitimate but controversial, not universally accepted.

Cultural Backdrop: Ancient Mesopotamian Norms Complicate Modern Views

One must remember that ancient societies did not share our modern categories about sexuality or friendship. Male relationships could be more physically and emotionally intimate without implying what we today call “romantic” or sexual connections. How does this affect the Gilgamesh-Enkidu debate?

For example, in many ancient cultures, including Mesopotamia, intense male bonds accompanied by affectionate language were often normal and celebrated. Think of the Biblical pair of David and Jonathan, whose relationship is famously close, described in deeply loving terms. Although some readers see this as romantic, most scholars consider it a profound friendship shaped by the norms of the time rather than a sexual relationship.

Ancient Mesopotamia was somewhat open to homosexual acts, but attitudes were complex. Historical records mention homosexual prostitutes and references to male lovers that are not judgmental. However, penalties existed for being the passive partner in same-sex relations, reflecting societal ideas about sexual roles and “natural” behavior.

These attitudes weren’t static. They evolved over the centuries. The laws and norms we understand best come from later periods, like 2,500–1,000 BCE, after the supposed time of Gilgamesh and Enkidu, who belong to Uruk around 3,000 BCE. This chronological gap makes it harder to apply later attitudes directly to their story.

The Role of Social Status and Sexual Roles

Interestingly, the importance of sexual roles is a recurring theme in the ancient world’s views on homosexuality. A man’s status could be challenged if he took on a “passive” role, considered shameful, especially for a citizen. Being dominant with a slave or male prostitute was less taboo. These nuances remind us that sexuality was often about power dynamics rather than just affection.

Some scholars, particularly in analyses like Cooper’s Buddies in Babylonia, emphasize that early Mesopotamian attitudes were more tolerant but still hierarchical. This complexity means we must resist simplistic labels.

Comparisons With Other Ancient Cultures: Is This Just “Bromance” Overload?

When we look at other ancient civilizations, we find similarly intense same-sex friendships that modern eyes might misconstrue. For example, Ancient Greece and Rome openly accepted male homosexual relationships but placed great importance on who penetrated whom, fluctuating moral judgments accordingly.

The takeaway? Ancient relationships often allowed “love” between men in powerful emotional or sexual ways, but their meanings were different from today’s categories of gay, straight, or bisexual.

What Does All This Mean for Gilgamesh and Enkidu?

The beauty of their relationship lies in its ambiguity and depth. Historians and literary scholars acknowledge hints of homoeroticism but caution against definitive conclusions. It might be a case of lost meanings, cultural gaps, and poetic symbolism that make the bond appear romantic to us.

Moreover, the actual surviving texts are incomplete and fragmented, and much of what we “know” about ancient Mesopotamian attitudes comes from later times. Therefore, we must tread carefully when interpreting these ancient stories through modern lenses.

Practical Tips for Readers

- Read with an open mind. Appreciate the epic as a story of powerful friendship and alliance that resonates across time.

- Consider cultural context. Understand that ancient societies framed relationships differently than we do now.

- Explore multiple translations. Some English versions gloss or soften suggestive language; others highlight it.

- Engage with scholarly debates. Reading articles by Jacobsen, Cooper, and others can deepen your understanding of the nuances.

- Still curious? Compare Gilgamesh and Enkidu to classical pairs like David and Jonathan or Achilles and Patroclus for a fuller picture of ancient male bonds.

So, Is It Romantic?

Let’s not rush. The relationship between Gilgamesh and Enkidu can certainly feel romantic to us modern readers. The intense emotions, the tender dreams, the companionship at life’s edge—these elements invite many interpretations.

Historians say: yes, there might be a homoerotic subtext, but there’s no hard consensus. The cultural norms of ancient Mesopotamia and the fragmentary nature of the sources mean that the question remains open. Their bond is one of the earliest and most powerful portrayals of male friendship—perhaps just stronger and deeper than what we’re used to seeing in ancient texts.

In other words, Gilgamesh and Enkidu bring ancient friendship to life in ways that challenge us. Whether romantic or platonic, their story shows us the timeless human craving for connection.

“The Epic of Gilgamesh leaves a remarkable space for interpretation: its heroes invite us to redefine how we think about friendship, love, and the meanings in between.”