Roman concrete was not used for centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire primarily because the imperial system that financed and demanded large-scale innovative construction vanished, removing the main driver for its spectacular applications. Without emperors’ funding ambitious projects, Roman concrete largely reverted to a utilitarian role in building. The shift caused by the loss of centralized sponsorship, coupled with conservative building practices, regional material differences, and political instability, all contributed to the prolonged disuse of Roman concrete’s full potential.

The Roman Empire’s emperors were the key patrons of monumental architecture. Concrete reached its architectural peak when imperial funding supported large projects, such as the Colosseum, Pantheon, and Baths of Caracalla. These structures showcased advanced uses of Roman concrete, including massive domes and vaults that relied on the “secret ingredient” pozzolana—a volcanic ash that made concrete strong and durable, even underwater.

Concrete before the imperial era was relatively basic. Builders employed it mainly as a filler material for thick walls, with brick facings concealing rubble and concrete cores. Roman architects of the early Republic had no formal training or tools to model structural forces mathematically. Their approach was cautious, applying concrete conservatively to avoid failure. Concrete’s aesthetic and structural potential emerged notably only when emperors demanded innovation and had the wealth to finance large scales.

Provincial concrete usage varied due to differences in local materials and traditions. While Italian concrete generally used pozzolana, volcanic ash deposits in other parts of the empire sometimes substituted. Although pozzolana was occasionally transported to provincial coastal cities, local masonry skills often prevailed. In the Greek East, for example, stone remained the preferred material for domes and walls, limiting concrete’s spread and reducing reliance on it for monumental architecture outside Italy.

After the western Roman Empire fell, the immediate loss of imperial patronage caused a steep decline in grand concrete construction. However, Roman concrete was not forgotten overnight. In the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, Emperor Justinian used hydraulic concrete to construct infrastructure like the harbor of Constantinople and embedded brick in concrete domes in structures like Hagia Sophia. These efforts, however, ceased within a century amid political turmoil and economic decline.

The general instability following Justinian’s reign ended monumental building programs that relied on large investments in concrete construction. Over time, skilled use of concrete became rare, and literary mentions of the material’s use nearly disappeared. Concrete vaults and domes fell into the category of lost technologies, remembered only as relics of a vanished era.

Roman concrete’s innovation hinged on pozzolana. This volcanic ash created a chemical reaction when mixed with lime and water, allowing concrete to harden underwater and increase strength in marine environments. This property enabled Romans to build durable harbors and underwater structures. Buildings fashioned with pozzolana concrete endure today largely intact, demonstrating its durability and highlighting the technological leap it represented.

In contrast, where pozzolana was not available, crushed terracotta often replaced it, diminishing the concrete’s durability. This practical improvised substitution further limited widespread adoption and appreciation of advanced Roman concrete techniques across the empire.

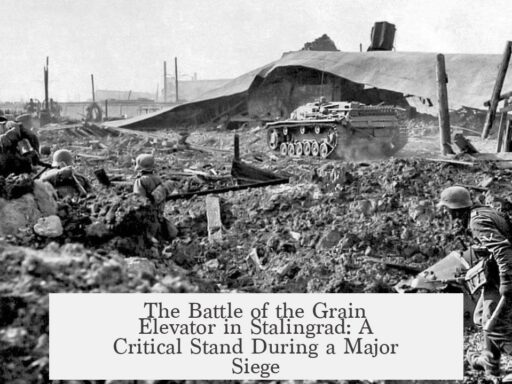

| Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Imperial Sponsorship | Loss of emperor-backed funding ended massive, innovative concrete projects |

| Architectural Conservatism | Builders lacked training, used concrete mainly as filler, avoided risky innovations |

| Regional Material Variations | Limited availability of pozzolana; local traditions favored stone masonry over concrete |

| Political and Economic Instability | After Empire’s fall, disruptions halted monumental construction and technological progress |

| Loss of Knowledge | Concrete vaulted domes and chemical knowledge were forgotten for centuries |

Roman concrete’s disappearance from large-scale construction was not a mere accident but the result of multiple intertwined causes:

- The empire’s centralized funding ceased, removing motivation and resources for grand projects.

- Conservative building cultures persisted, lacking formal engineering or mathematical planning.

- Natural resources like pozzolana were unevenly available, restricting advanced techniques geographically.

- Political collapse and economic decline disrupted skilled labor and infrastructure investment.

- Over generations, knowledge of specific concrete formulas and construction methods faded.

Only centuries later did new building techniques and materials revive concrete usage in Europe. Modern concrete, discovered anew, eventually surpassed Roman formulas with Portland cement, but the Roman invention set an early and lasting precedent.

Key takeaways:

- Roman concrete flourished under imperial sponsorship with the wealth and demand for monumental building.

- Before imperial patronage, concrete use was basic and conservative, mostly filler in thick walls.

- Regional material differences limited widespread adoption of pozzolana concrete outside Italy.

- Political and economic instability after the empire’s fall halted large concrete projects and caused loss of technical knowledge.

- Roman concrete’s unique strength came from pozzolana volcanic ash, a chemical innovation lost for centuries after the empire.

Why Was “Roman Concrete” Not Used for Centuries After the Fall of the Empire?

Simply put, Roman concrete was not used for centuries after the empire’s fall because the collapse of imperial power cut off the huge funding and bold innovation needed to build with it at scale. Without emperors backing majestic projects, concrete’s role shrank. It reverted to just a filler material in humble walls. But that’s only the headline — the full story is far richer and contains lessons about innovation, chemistry, and history that still fascinate engineers and historians today.

Let’s peel back the layers and see why the magic of Roman concrete vanished for centuries. And don’t worry – this tale has a few surprises alongside ancient rubble.

1. Imperial Sponsorship: The Emperor’s Checkbook Was Key

The Romans needed more than good materials — they needed an emperor with a vision *and* a bank account large enough to fund colossal projects. Think of emperors as the original venture capitalists for architecture.

“Without emperors to sponsor massive and innovative building projects, there was little need for the spectacular uses of concrete.”

Big players like Nero pumped imperial money into revolutionary buildings — the Colosseum, the Pantheon with its mind-boggling concrete dome, and the Baths of Caracalla. These weren’t just buildings; they were statements of power and engineering prowess supported by the imperial treasury.

But outside the capital, concrete got treated like your average house repair material. Wealthy citizens, not emperors, footed the bill. The result? More modest projects with conservative designs.

“Once the emperors stopped paying for large-scale construction projects, concrete largely reverted to what it had been before the Roman architectural revolution: a useful filler for thick walls.”

Imagine innovation dripping away as funding dries up — economic muscle was the catalyst.

2. Builders Were Cautious, Not Mad Scientists

Contrary to popular belief, Roman architects didn’t leap wildly into new techniques. They lacked formal training and tools like modern math or stress modeling. Their approach leaned heavily on time-tested methods — cautious and conventional.

Roman builders “tended to be very conservative in their use of building materials.”

Roman concrete was initially a time-saving trick to fill walls quickly with rubble and bricks rather than a star player for architectural innovation. The daring vaults and domes only came with imperial demand and funding.

This conservatism reminds us that technology alone doesn’t spike innovation — social and economic factors shape how materials are used. Without bold patrons, the monolithic Roman concrete achievements might never have materialized.

3. Geography and Ingredients Played Their Part

Not all concrete was created equal. The secret sauce? Pozzolana, a volcanic ash from Italy’s Campanian coast. It made Roman concrete exceptionally strong, able to set underwater and grow stronger when soaked in saltwater. Perfect for harbors!

“Roman concrete differed from Roman mortar by virtue of its ‘secret ingredient’ — pozzolana.”

But this ash wasn’t everywhere. Coastal cities across the empire sometimes got shipments of pozzolana, but plenty of provincial regions relied on less effective substitutes like crushed terracotta or local volcanic ash.

The Greek East, for example, clung to superior stone masonry traditions instead of embracing concrete for grand domes. This regional variation shaped the scale and style of concrete use, limiting the replication of Roman marvels away from Italy.

4. Political Upheaval and the End of the Empire

After the Western Roman Empire fell, chaos followed — no surprise. Concrete didn’t immediately disappear but faded fast with political instability and shrinking resources.

The Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire kept some traditions alive. Procopius praised Emperor Justinian for using hydraulic Roman concrete to build a harbor in Constantinople. Justinian’s iconic Hagia Sophia even used brick embedded within concrete domes.

“Concrete vaults and domes became, like so much else across the former Roman world, mementos of a vanished past.”

But after Justinian, political troubles shut down grand construction efforts. Concrete vaulted innovations vanished from textbooks and building sites alike for centuries. It became a lost art until rediscovered in the modern era.

5. Chemistry and Innovation: A Gift Lost Then Regained

Roman concrete’s superpower was chemistry — the pozzolana volcanic ash turned simple mortar into a durable, water-resistant concrete. This was far ahead of its time. It even hardened underwater and grew stronger in saltwater, qualities the Romans used extensively for maritime constructions.

Yet, the chemical principles were a mystery to them. Romans used concrete practically without knowing why it worked so well. This meant the knowledge stayed local and experimental, vulnerable when the empire dissolved.

Additionally, not all uses of concrete had pozzolana. Some regions used terracotta chips as a cheaper substitute, which didn’t perform as well. This inconsistent quality may also have slowed the adoption and transmission of Roman concrete expertise.

So Why the Multi-Century Silence?

When you squeeze it, the reasons are clear:

- The loss of imperial funding cuts off large, daring projects. No emperor = no concrete revolution.

- Roman architects were cautious; without financial and political backing, they reverted to simple, known methods.

- Poisonously regional materials like pozzolana limited widespread use of true Roman concrete.

- Post-Roman political turmoil put a pause on monumental construction, and concrete techniques faded from use and memory.

- The chemistry edge of Roman concrete was lost as practical knowledge became fragmented without scientific documentation.

It’s a fascinating reminder that technology doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Powerful patrons, stable governments, local resources, and knowledgeable engineers must all align. When one falters, even the greatest inventions can disappear.

What Can Modern Builders Learn?

Modern concrete owes a nod to Roman innovation. Today’s engineers have scientific tools and global materials access that ancient builders lacked.

Still, the ancient experience encourages us to:

- Value funding for innovation. Without investment, breakthroughs languish.

- Preserve and document material science knowledge rigorously.

- Consider ecological and regional sustainability in material sourcing — like how Rome’s volcanic ash gave their concrete unmatched durability.

Perhaps, next time you walk past a concrete structure, you’ll imagine a vast empire led by emperors who knew how to harness ash and sand to build wonders that lasted millennia — until history pulled the plug, leaving us to rediscover what they once mastered.

How remarkable that something as humble as volcanic ash and rubble could etch the Roman Empire into history — and also vanish from practice for centuries, waiting for a new age to revive it. Would modern society survive without continued innovation and support for engineering? Food for thought.