The ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians exhibited varying degrees of openness toward homosexuality, shaped by different cultural, social, and legal frameworks. While male homosexual behavior was often visible and sometimes tolerated or celebrated in Greece and Rome, the concept of homosexuality as a modern identity was absent. In contrast, ancient Egypt shows ambiguity, with little explicit evidence but some recognition of same-sex relationships, framed largely by social norms rather than strict prohibitions.

The idea of homosexuality itself needs clarification. Three different concepts exist: homosexual behavior (sexual acts between people of the same sex), homosexual orientation (innate attraction), and homosexual identity (self-identification based on behavior or attraction). Ancient societies did not distinguish these as we do today. Scholars debate whether sexual identities as understood now were present in antiquity, often concluding that identities are modern constructs. This means ancient openness cannot be measured by today’s standards of orientation or identity but rather by observable behaviors and societal reactions.

In Ancient Greece and Rome, acceptance of male homosexual behavior was culturally embedded but complex. In Greece, male homosexuality was often practiced as pederasty, involving an adult male and an adolescent boy. Such relationships were socially accepted within strict age and role norms. Sexual roles mattered deeply. The penetrating partner maintained social dominance and masculinity. Similarly, Rome accepted same-sex activity only if a citizen took the active role and the passive partner was a slave or foreigner.

- Greek society celebrated male-male relationships but disdained adult men who took a passive, penetrated role, viewing them as socially inferior.

- Marriage and procreation remained social obligations regardless of extramarital homosexual behavior.

- Female homosexuality in these cultures rarely appears positively and was often stigmatized, with scant literary or artistic evidence.

This acceptance was not about sexual orientation or identity but about social order, power, and roles. Sexual acts were seen as active or passive, with stigma attached to passivity in men. Prior to Christianity’s rise, this shaped a distinct environment of tolerated male homoerotic behavior within strict bounds. However, same-sex activity outside this framework or female homosexuality often faced hostility or invisibility.

In ancient Egypt, the picture is more ambiguous. The Egyptian language and art offer limited clear evidence of homosexual relationships. For example, the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep shows two men in intimate poses interpreted by some Egyptologists as evidence of a same-sex couple, yet both men had wives and children. Similar ambiguities exist in depictions of women like Idet and Ruiu. This ambiguity reflects challenges in interpreting same-sex affection in Egyptian culture.

Ancient Egyptian literature rarely addresses homosexuality directly. One tale, that of Pharaoh Neferkare and General Sasenet, hints at male same-sex relations but criticizes it. Overall, social norms emphasized marriage and procreation for men and women alike. The strongest pressure against homosexual behavior came from social expectations rather than explicit legal or religious prohibitions. Some texts suggest homosexual acts, especially penetration of a man, might be frowned upon or carry derogatory implications.

- Sexual penetration had symbolic meanings linked to masculinity and power, sometimes associated with emasculation or loss of status when reversed.

- Mythological stories include ambiguous or negative references to homosexual desire and dominance.

- Egyptian burial texts, such as some versions of the Book of the Dead, include vows against penetrating men, indicating disapproval in certain ritual or social contexts.

Ancient Egyptian society was not openly repressive nor openly accepting but rather socially cautious about homosexual relationships. They lacked systematic persecution but promoted heterosexual marriage and procreation strongly. Social norms likely discouraged open homosexuality more than law or religion.

The assessment of openness about homosexuality in these ancient cultures requires caution. Modern categories of sexual orientation and identity do not map neatly onto ancient frameworks. The Greeks and Romans were openly tolerant in terms of male homosexual behavior within set social roles. Egyptian evidence remains ambiguous, with social norms playing a dominant role, neither affirming nor outright rejecting homosexuality.

Overall, the historical record presents mixed evidence. The ancient Greek and Roman openness is best understood as conditional acceptance tied to social hierarchy and gender roles, not a general celebration of same-sex love or identity. Egypt’s position is more ambiguous, with respectful or affectionate same-sex expressions visible but constrained by social expectations. Modern interpretations must avoid anachronisms and recognize the significant cultural differences shaping ancient attitudes.

- Ancient Greek and Roman societies tolerated male homosexual behavior but enforced strict social roles and gender norms.

- Female homosexuality appeared limited and often stigmatized in these cultures.

- Egyptian evidence is ambiguous, with some intimate same-sex relationships depicted but shaped by social conventions rather than laws.

- Modern sexual identities did not exist in antiquity; thus, openness must be considered in historical context.

- Social pressures regarding marriage and procreation strongly influenced attitudes toward homosexual acts in all three cultures.

Were the Ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians Really More Open About Homosexuality?

Yes, ancient Greeks and Romans exhibited a certain level of openness toward male homosexual behavior, particularly before Christianity influenced social norms; however, this openness came with clear social rules and limitations. Ancient Egypt, meanwhile, presents a much more ambiguous picture with little direct evidence, reflecting social ambivalence rather than explicit acceptance or outright rejection. But what does this really mean? Let’s break it down with some facts, cultural insights, and clarifications.

When we toss around the term “homosexuality” about these old civilizations, it’s tempting to imagine their people were cruising Athenian agorae or lounging Roman baths with pride flags. Reality? Not quite.

Three Shades of Homosexuality: Behavior, Orientation, and Identity

First, the ancient world doesn’t hand us a simple map labeled “homosexuality.” It’s more like a palette with different shades:

- Homosexual Behavior—Physical or romantic activity between people of the same sex.

- Homosexual Orientation—Innate or enduring desires someone might have for same-sex partners.

- Homosexual Identity—How one labels themselves based on behavior or orientation.

Modern scholars debate vigorously whether ancient people experienced or expressed orientation or held fixed identities like today’s LGBTQ+ communities. The consensus leans toward the idea that sexual behavior happened without necessarily forming identities akin to ours. In other words, no ancient “homosexual pride parades,” but various behaviors did occur.

The Greeks and Romans: Openness Within Boundaries

Ah, Ancient Greece and Rome—the poster children of “sexual freedom” in classical studies. Was homosexuality embraced? Well, yes and no.

Before Christianity’s rise, male homosexual behavior in Greece and Rome held a semi-accepted place in society. Men could engage in such activities openly, without legal persecution or automatic social exile. Families could know, even friends, without the stigma familiar today—at least in certain circles.

However, this “openness” came with strong social rules.

- In Greece, most homosexual relations fit into the controversial practice of pederasty—a socially structured bond between an adult man and an adolescent boy. This was more about mentorship and socialization than modern same-sex relationships, with an unsettling age gap reflecting broader cultural norms.

- The Romans also allowed male homosexual acts but only if the Roman citizen remained the “dominant” or penetrating partner. Their sexual ethics revolved around dominance and submission, so the passive partner—especially if an adult male Roman citizen—was socially scorned.

- Being the “bottom” was a status no respectable citizen wanted. It implied loss of status, weakness, or shame.

Female homosexuality? It barely registers in the record and when it does, it’s often with suspicion or negativity. Women stepping outside normative roles faced harsh judgment.

So, were these societies open? Yes, but only within a tightly framed set of social roles and expectations. Marriage and procreation remained compulsory for social stability, yet homoerotic behavior among men, ranged from tolerated to celebrated in very particular contexts.

Ironically, the reason people think ancient Rome or Greece were super “gay-friendly” stems from misunderstanding ancient sexual ethics. Sex was viewed through the lens of roles—active penetrator vs. passive penetrated—rather than who you loved or identified as. Being actively dominant was a mark of masculinity and power.

Egypt: A Puzzle Wrapped in Hieroglyphs

Enter Ancient Egypt, where the picture gets fuzzy. Unlike Greece and Rome, Egypt’s attitude toward homosexuality is like trying to solve a riddle in a language still partially unknown.

Here, the evidence is limited, ambiguous, and often symbolic rather than explicit.

The language and art of the time don’t provide a clear “Yes” or “No” answer. For example, relationships like that of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep, two men buried together with loving touches and intimate gestures, raise eyebrows.

- These men’s depiction is tender, holding hands and touching faces, which could suggest romantic bonds.

- But they were both married to women and had children, complicating the assumption of a sexual relationship.

- Also, alternative explanations exist: they might have been brothers, close friends, or ritual partners.

A similar conundrum appears with women like Idet and Ruiu, whose close depictions in statues could be lovers or relatives. Egyptologists often require ironclad proof to label these relationships “homosexual,” which remains scarce.

Legally, there is no clear condemnation or criminalization of homosexual acts comparable to what happened in other cultures. Homosexual acts sometimes appear on lists of misdeeds in funerary texts. This likely signifies social disapproval, but not harsh legal punishment.

Mythology adds to the ambiguity—stories like that of Seth attempting to overpower his nephew hint at sexualized dominance and emasculation themes rather than consensual same-sex desire. Egyptian literature emphasizes heterosexual marriage and procreation as ideals, but evidence suggests extramarital or “irregular” sex happened too.

The important takeaway: Egyptian society seems to have tolerated but not celebrated same-sex acts, with social norms, rather than strict laws, guiding behavior.

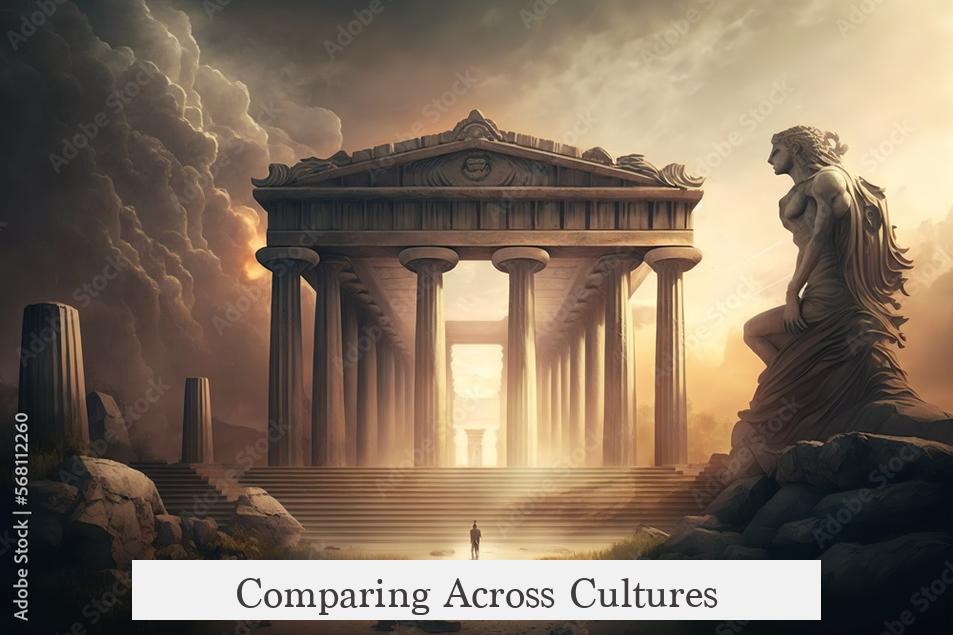

Comparing Across Cultures

So, how do these ancient views stack up against each other—and against today’s standards?

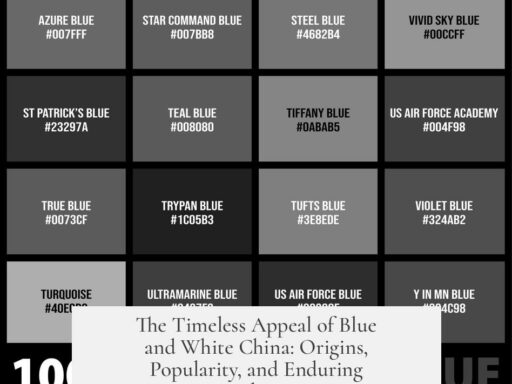

| Aspect | Ancient Greece | Ancient Rome | Ancient Egypt |

|---|---|---|---|

| Legal Status of Male Homosexual Acts | Legal and socially tolerated in specific contexts | Legal if citizen was dominant partner; socially regulated by power dynamics | No explicit laws; social norms discouraged but vague |

| Female Homosexuality | Rarely documented; often negatively portrayed | Poorly documented; marginal role | Ambiguous; scant evidence |

| Social Norms | Marriage and procreation expected; pederasty accepted among men | Citizen dominance key; passive male partners stigmatized | Emphasis on heterosexual marriage; ambiguous attitudes toward same-sex affection |

| Sexual Identity Concept | Absent; acted more on behavior and roles | Absent; identity not defined by orientation | Likely absent; affection terms ambiguous |

What Can We Learn?

The idea that ancient people were “more open” about homosexuality doesn’t quite fit modern expectations. They didn’t have identities the way we do. They judged sexual behavior based on social roles and power rather than attraction or love. Openness, in their terms, depended heavily on factors like age, rank, gender roles, and dominance dynamics.

Consider this: Ancient Greek and Roman men engaging in same-sex acts did so openly as long as they preserved social hierarchies. Being the passive partner was humiliating and could damage one’s social standing. Women faced stricter norms with little space for same-sex affection, often erased or misinterpreted by historical narratives.

Meanwhile, Ancient Egypt skirts the line, giving us tantalizing but unclear glimpses of same-sex affection and relationships. Their norms depended more on family and social expectations, with no clear laws punishing homosexual behavior.

So, these societies were open but not in a way that reflects modern acceptance or LGBTQ+ identity politics. The “openness” was more a reflection of social codes than free expression.

Why Does This Matter Today?

Understanding ancient attitudes reminds us how flexible and varied human sexual norms can be, but also the dangers of projecting modern ideas onto past lives.

Modern sexuality involves identity and personal narrative, while ancient sexuality often rested on actions within societal hierarchies.

Yet it proves one thing loud and clear: civil rights and acceptance today do not depend on ancient precedents or “proof” of homosexuality in history. Those who experience same-sex attraction deserve respect and equality, regardless of what the old scrolls say or don’t say.

Wrapping Up

Were the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians really more open about homosexuality? The honest answer is complicated.

- Ancient Greek and Roman societies tolerated certain male homosexual behaviors, especially those fitting social power roles, but these came with limits and harsh judgments against perceived weakness.

- Ancient Egypt’s case shows social ambivalence, with affectionate imagery but scarce explicit evidence or legal frameworks.

- Modern ideas of sexual orientation and identity don’t map neatly on these ancient contexts.

They weren’t exactly throwing rainbow parties, nor were they fiercely persecuting. Instead, they lived complex, coded sexual lives shaped by social hierarchy, gender norms, and cultural meanings different from ours today.

So, next time you hear the phrase “ancient acceptance of homosexuality,” remember to ask: acceptance by whose standards? The past’s rules were a different game entirely.