Jerry Lewis becomes exceptionally popular in France due to French film critics embracing him as a filmmaker under the auteur theory, unlike the mainly dismissive American critical view focused on his slapstick comedy. This distinct reception begins as Lewis transitions from actor to director around 1961, a shift that aligns with France’s cultural emphasis on the director as the true author of a film.

In the United States, Lewis enjoys broad popularity with general audiences. However, American critics largely reject his style, viewing it as mere slapstick lacking artistic merit. Andrew Sarris notes that while Lewis continued to make money and found an audience, he never sparked serious critical dialogue about the quality of his work. This disconnect leaves Lewis as a popular entertainer but critically underappreciated at home.

French critical opinion initially mirrors some American skepticism. Early reviews by critics like Gilbert Salachas and Jean-Pierre Coursodon describe Lewis’ comedy as tedious or even degrading. Despite this rough start, French critics soon reconsider when Lewis directs his own films.

The turning point comes in 1961, when Lewis moves into directing. French critics, heavily influenced by the auteur theory, begin to study his films as personal artistic statements. This theory prioritizes the director’s vision as central to understanding a film’s value. Lewis fits this ideal perfectly because he writes, directs, and stars in his movies, wielding creative control.

Publications such as Cahiers du Cinéma praise Lewis’ directorial work, describing it as innovative and dreamlike. Critics like André S. Labarthe and Claude Ollier analyze films such as The Nutty Professor with deep appreciation for their complex humor and narrative sophistication. The film even tops Cahiers du Cinéma’s 1963 best film list, a high honor that firmly establishes Lewis as a respected auteur.

This French critical respect significantly contrasts with other American slapstick stars, who do not receive similar auteur recognition in France. For instance, Louis de Funès, despite high French popularity, is not critically elevated to Lewis’ level, partly because he does not write or direct his films. Lewis’ status as a filmmaker distinguishes him.

Further cementing Lewis’ popularity, his 1965 visit to Paris for Boeing Boeing draws enthusiastic public and critical acclaim. He receives direct awards for his direction, and critics present these honors openly. Lewis describes this experience as the greatest career satisfaction he has ever known, highlighting the strength of French admiration.

Despite this admiration, a myth forms in the American media portraying Lewis as scorned in his home country but wholeheartedly embraced by France. Some American outlets frame French praise dismissively, implying that Lewis must rely on foreign approval due to domestic decline. This narrative overlooks Lewis’ ongoing American popularity and the nuanced nature of his international reception.

This French fascination with Lewis also intersects with mid-1960s cultural and political tensions between the US and France. His popularity stands out as a cultural bridge during a period of strained diplomatic relations, reinforcing French critics’ distinct perspective on his films.

| Factor | Explanation |

|---|---|

| American Reception | Popular with the public but rejected by critics because of slapstick focus |

| French Auteur Theory | Critics evaluate film as director’s personal work; Lewis became viewed as auteur |

| Directorial Shift | Lewis directing from 1961 triggers critical re-evaluation and praise |

| Cahiers du Cinéma Praise | Considered The Nutty Professor a top film; admired for innovation and complexity |

| Personal Recognition | 1965 Paris visit marks symbolic embrace by French audience and critics |

| Myth of Exclusive Admiration | American media exaggerates the idea Lewis is scorned in US but loved in France |

- Lewis gains French popularity by becoming an auteur director embraced by French critical theory.

- French critics award his films intellectual respect absent in American reviews.

- The transition to directing in 1961 begins French critical praise and reappraisal.

- The Nutty Professor is a landmark French favorite and symbolizes his auteur status.

- 1965 Paris visit reinforces Lewis’ personal connection to French audiences.

- French admiration contrasts with American critical dismissal, fueling a cultural myth.

How Did Jerry Lewis Become So Popular in France?

Jerry Lewis owes his enormous popularity in France to a unique blend of cultural appreciation and critical recognition that sharply contrasts with his reception in America. While U.S. audiences embraced his slapstick comedy, American critics largely dismissed his work. France, in turn, elevated Lewis to the status of an auteur—a true cinematic artist—especially after he directed his own films.

But why France? And how did this admiration blossom into a genuine, almost mythic status? Let’s unpack this fascinating story of cinematic cross-cultural affection.

A Tale of Two Receptions: America vs. France

In the U.S., Jerry Lewis is a household name—lightning fast with physical comedy, goofy faces, and an unmistakable charm. The American public loved him. He transitioned seamlessly from nightclubs to radio to television and then to movies. Box office? Check. Popularity? Double-check.

However, here’s the kicker: American critics rarely valued his comedic style. Slapstick, to them, felt low-brow, sometimes “despicable.” Critics like Andrew Sarris noticed that once Lewis began directing in the 1960s, the intelligentsia turned their backs. Lewis remained popular with the masses, but serious critical conversation was minimal.

“Lewis was liked by the public and ignored by American critics, who found his antics despicable.”

– Film critic Andrew Sarris

In stark contrast, French film critics viewed Lewis through the lens of the emerging auteur theory. This was a game-changer. The theory, born in the 1950s and ’60s, posited that a director is the “author” of a film, whose style and thematic choices merit deep analysis.

Applying auteur theory, French critics placed Lewis alongside legendary directors like Alfred Hitchcock or Howard Hawks, especially when he began directing his own films. Suddenly, he wasn’t just a funnyman; he was a creative genius crafting complex cinematic worlds.

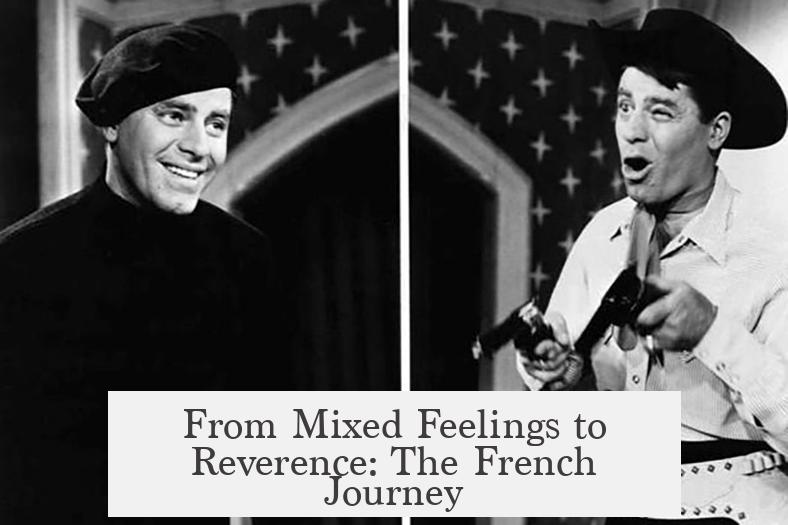

From Mixed Feelings to Reverence: The French Journey

Early French critics were not all enchanted. Figures like Gilbert Salachas and Jean-Pierre Coursodon expressed confusion and distaste. Salachas couldn’t grasp why the masses adored Lewis’ “laborious idiocies,” and Coursodon called his films “physically close to intolerable.” Harsh, huh?

“Jerry Lewis seems to us to represent the lowest degree of physical, moral, and intellectual debasement.”

– Jean-Pierre Coursodon, 1960

The turning point? Lewis stepping behind the camera himself. From 1961 onward, when he directed classics like The Bellboy, Cinderfella, and particularly The Ladies Man, French critics took note. They saw a consistent, personal vision emerge: the hallmark of a true auteur.

This new lens positioned Lewis alongside silent film giants Chaplin and Keaton, not as a clown, but as a visionary filmmaker.

“It is only when Lewis started directing movies in 1961 that French critics… started to treat him with reverence…”

French Critics Didn’t Just Like Lewis—They Analyzed Him

French cinema magazines like Cahiers du Cinéma played a huge role. André S. Labarthe’s 1962 article hailed Lewis for creating “dreamlike, topsy-turvy cinematic worlds” that defied traditional comedy molds.

Later, Claude Ollier’s 1964 deep dive into The Nutty Professor explored how Lewis simultaneously matured a character and created an almost oneiric cinematic universe—a rare compliment for a comedy.

“Jerry Lewis carried out two operations at the same time… the maturing of a character… and the elaboration of a universe tending towards a total oneiric representation.”

– Claude Ollier on The Nutty Professor, 1964

The respect was real. The Nutty Professor was ranked tops for 1963 by critics, outranking many serious international films. This scholarly approach separated Lewis from other slapstick comedians, even popular French ones like Louis de Funès, whose work critics saw as less “auteur-driven.”

Jerry Lewis as a French Cultural Icon

By 1965, Lewis wasn’t just a filmmaker; he was a cultural phenomenon in France. His visit to Paris during the filming of Boeing Boeing was met with enthusiastic crowds and critical applause. He received an award for best direction for The Nutty Professor, a moment Lewis called “the greatest satisfaction I have ever known in my career.”

“He was mobbed at the airport then at a news conference… The summit of Jerry’s happiness… when the critics presented him with an award for best direction because of The Nutty Professor.”

This event cemented his adored status in France and sparked a narrative in the U.S. media: Lewis was loved abroad but scorned at home.

The New York Times dubbed him Le Roi du Crazy (The King of Crazy), a label loaded with irony. Shawn Levy points out this reflected Lewis’ dwindling U.S. audience and his need for validation from what some Americans saw as an “obscure foreign cult.”

This cross-Atlantic difference in appreciation unfolded during challenging political times, with the U.S. and France experiencing tense relations. Meanwhile, France maintained and nurtured its love for Jerry Lewis—a comedian celebrated as an auteur and artist.

Why Does This Matter Today?

Beyond trivia about a 20th-century comedian, Lewis’ French popularity challenges us to think about how culture and criticism shape fame. Is popularity just about box office numbers? Or is it about critical appreciation and artistic respect? France’s embrace of Lewis shows how perspective changes everything.

For filmmakers or creatives today, the lesson is clear. Sometimes, genuine recognition comes not from your home crowd but from those who see the deeper meaning behind your work. Like Jerry Lewis, success may mean transitioning from mere entertainer to thoughtful auteur in the eyes of discerning audiences.

Practical Takeaways

- For Creators: Embrace creative control. Lewis’ directorial ventures won him serious acclaim.

- For Fans: Different cultures interpret art uniquely. Don’t dismiss praise just because it seems “foreign.”

- For Critics: Look beyond surface-level entertainment. Comedies can host complex themes and innovation.

So, next time someone wonders why Jerry Lewis is practically a saint in France, you can explain it’s a brilliant mix of auteur theory, cultural taste, and Lewis’ own leap into film direction.

Who knows? Maybe there’s a bit of Jerry Lewis hidden inside every misunderstood genius waiting for the right audience to come along.

Why did French critics begin to admire Jerry Lewis when American critics did not?

French critics valued directors as auteurs, or true authors of their films. When Lewis started directing in 1961, they saw his work as original and innovative. American critics mainly focused on his slapstick style and often dismissed him.

How did Jerry Lewis’ role as a director influence his popularity in France?

His directorial efforts showed artistic depth that matched French auteur theory ideals. Films like The Nutty Professor were praised as creative and dreamlike, leading French critics to regard him as a serious filmmaker.

What was the reaction in France when Jerry Lewis visited in 1965?

He was warmly received and honored by critics, who gave him an award for best direction. The public and critics showed enthusiasm and respect, making it a high point in his career.

How did the French admiration for Jerry Lewis differ from the American perspective?

While American critics mostly ignored or disliked Lewis’ slapstick films, French critics celebrated his unique vision as a director. This contrast made Lewis more of an auteur figure in France than in the U.S.

Did the political climate between France and the U.S. affect Lewis’ reception in France?

Yes. During the mid-1960s, political tensions made French admiration for Lewis stand out. His popularity there was sometimes seen as a cultural counterpoint to declining U.S. interest.