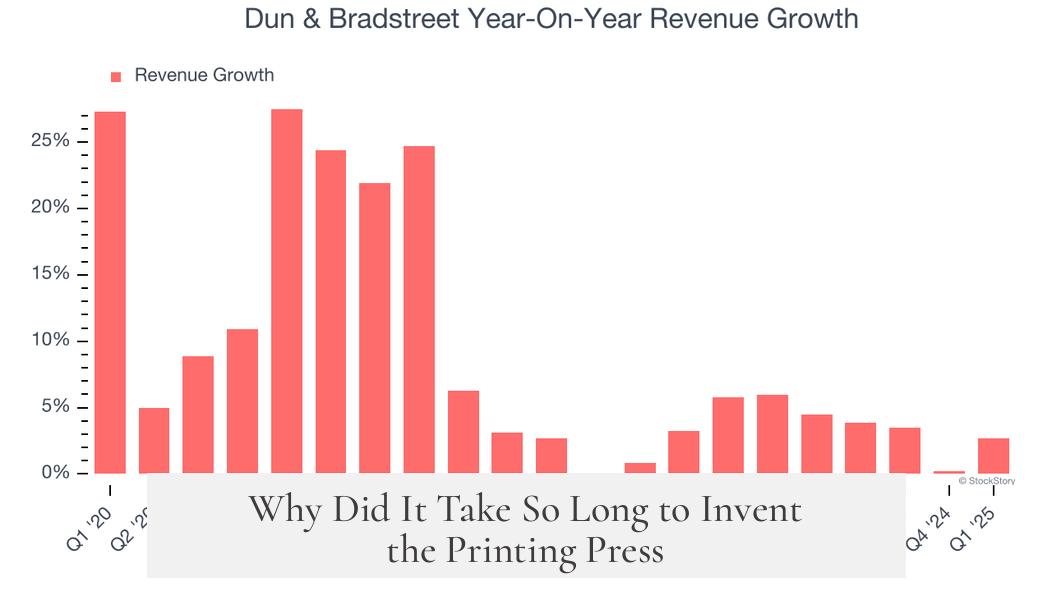

The printing press took a long time to be invented because the need and market demand for mass-produced books only emerged in the 15th century, after centuries of on-demand, luxury book production limited by materials, literacy rates, and inefficient copying methods.

Before the printing press, books were rare and costly. Monasteries or wealthy patrons requested manuscripts. Scribes copied texts by hand, which took great labor and time. The main material, vellum or parchment, was expensive. This animal skin required careful processing. Inked pages could be scraped and reused. Such luxury objects were beyond the reach of most people.

Paper entered Europe gradually from the Islamic world in the 14th century. It became common in Germany around 1400. Paper was cheaper than vellum but scribes still wrote each copy. Labor and skill demands kept book production limited and costly.

Early attempts at faster book production occurred. In 1427, Dietrich Lauber’s Hagenau workshop organized scribes to copy parts of a text simultaneously. This assembly-line approach aimed to boost supply and drive demand. Lauber also launched extensive letter-writing campaigns to market his books.

Technology attempts like woodblock printing existed but proved inefficient. Carving entire pages onto woodblocks was laborious and inflexible. Johannes Gutenberg, a goldsmith, made the key innovation: movable metal type molds using an injection mold method. Individual letters could be rearranged and reused. This revolutionized printing efficiency.

Yet Gutenberg’s press was only useful because the market had evolved. Low literacy in the Middle Ages meant few readers. Mostly clergy and nobles could read. Lay literacy grew slowly after the 12th century, but remained low overall. Typical households owned very few books, mostly religious texts.

The 15th century in Germany saw a surge in demand. The Council of Constance revitalized Church efforts to educate laity, pumping demand for handbooks and religious primers. Parish priests and preachers emerged as major buyers. Additionally, an expanding bureaucracy required educated secretaries, increasing demand for textbooks. Popular humanism from Italy grew among elites. Grammar schoolboys became a key reading group.

For the first time, sellers could confidently produce hundreds of copies of the same book and find buyers for all. This market confidence justified investment in mass production.

Between 1460 and 1490, the printed book evolved into a marketable object. Printers developed title pages and preferred vernacular texts, pamphlets, and certificates, which sold better than scholarly Latin works.

Key factors delaying the printing press:

- Insufficient need and market for mass-produced books before the 15th century

- Books as luxury items with expensive materials and specialized labor

- Low literacy rates and small lay book collections

- Early inefficient printing methods like woodblocks

- Slow adoption of cheaper materials like paper

- Only 15th century market growth among clergy, students, and bureaucracy justified mass production

- Gutenberg’s movable metal type enabling cost-effective reproducible printing

In short, the printing press was not just a technology invention but a response to cultural, economic, and educational changes that created a viable market for widely accessible books.

- Luxury, manual book production dominated until lower material costs and literacy increase.

- Innovations in organizing scribes and printing techniques gradually appeared before Gutenberg.

- Mass market demand emerged from clergy, students, and bureaucrats in 15th century Germany.

- Movable metal type enabled scalable, reusable printing adapting to this demand.

- The printing press is the intersection of technological and societal readiness.

Why Did It Take So Long to Invent the Printing Press?

The printing press took its sweet time to show up because the world just wasn’t quite ready for mass book production until the 15th century. The need, the market, and the tech all had to align perfectly. But why exactly did it take that long? Let’s dive in and explore the fascinating journey behind one of history’s greatest inventions.

First things first: inventions don’t just pop out like magic. Someone has to feel a pressing need, and that need must be strong enough to *justify the money and effort* spent on creating it. Before the 1400s, books were luxury items made very carefully, one at a time. The idea of churning out hundreds of copies didn’t even seem necessary or practical.

Books: Treasured Luxury, Not Mass Market in Medieval Times

Picture this: a medieval monastery, where a few highly skilled scribes with quills in hand painstakingly copy texts onto vellum—super thin, expensive animal skin pages. This wasn’t your local library’s printing routine; it was an exclusive, on-demand service for the elite. Vellum was costly, and parchment was precious—sometimes, scribes scraped off old ink just to reuse the pages. Yes, book recycling existed long before it was trendy.

More crucially, most people couldn’t read anyway. Literacy rates were abysmally low, hovering around a meager 10-15% in 1400, mostly among clergy and some nobles. A huge chunk of the population had little to no use for books, so mass printing seemed like shooting arrows into the void. Selling 500 copies of the same book? Nearly impossible.

Paper Arrives on the Scene—But Slowly

By the 14th century, paper started creeping into Europe from the Islamic world, trickling north until it finally took off around 1400 in the Holy Roman Empire (think modern Germany). Paper was cheaper than vellum and gradually made book production less pricy. Yet, despite this material breakthrough, books still required meticulous scribal labor and remained custom orders rather than mass products.

Early Attempts at Mass Production: Assembly Lines for Books?

Here’s a fun twist: around 1427, Dietrich Lauber tried to shake things up. Operating out of Hagenau, Lauber organized a workshop where multiple scribes tackled parts of the same text simultaneously. Think of it as a rudimentary assembly line but for scribes with ink-stained fingers. Lauber’s big bet was that if more books were produced, people would want to buy them — a classic *supply creates demand* approach. He then launched a massive letter-writing marketing campaign, reaching out to contacts in hopes of stoking interest before the books even got copied. Bold, right?

Still, this system, although innovative, was slow and costly compared to later printing methods.

Woodblock Printing: Too Much Work for Too Little Payoff

Before Gutenberg’s fame, woodblock printing tried to solve rapid copy production. Craftsmen carved entire pages into wooden slabs, which were then inked and pressed like giant stamps. Problem? Carving every page took ages, and tweaking a page required a whole new block carved from scratch. This method was neither efficient nor cost-effective. It was like trying to build a skyscraper with popsicle sticks—possible, but painfully tedious.

Enter Gutenberg: The Real Game-Changer

So what exactly did Gutenberg do that was so revolutionary? Spoiler: it wasn’t inventing the press itself. The printing press technology, involving pressing inked surfaces onto paper, existed in various forms beforehand. Gutenberg was a skilled goldsmith. His genius lay in creating the movable metal type molds using an injection-mold process. These tiny metal letters could be arranged, inked, pressed, and then reused endlessly. Suddenly, printing went from painstakingly hand-crafted to flexible and scalable production.

This breakthrough coincided perfectly with rising demand for books, setting the stage for rapid expansion.

Why Did Demand for Books Spike in 15th Century Germany?

The 15th century wasn’t just a renaissance in art and thought; it was a renaissance in reading needs. Two main groups drove this demand:

- Parish priests and preachers: After the Council of Constance (1414-1418), the Church prioritized educating the laity through preaching and teaching. This reform required practical handbooks and religious texts for clergy who needed materials to instruct their congregations. Suddenly, thousands of priests needed affordable, accessible books.

- Students and bureaucrats: Grammar schools expanded, educating mainly boys who needed primers and grammars. Meanwhile, growing bureaucracies required educated secretaries who needed literacy skills—and thus books. The intellectual trends of the time, such as ‘popular humanism’ spreading from Italy, added fuel to the fire.

Put these groups together, and suddenly there’s a solid market that can absorb hundreds of similar books—something unthinkable just a century prior. Printers could now confidently produce 500 copies, knowing they’d likely sell them all.

Books Become Marketable Products

The decades after Gutenberg’s first printed books (the 1460s to 1490s) show a rapid evolution in the book market. Printers added title pages and moved them to the front cover. They learned that vernacular works, pamphlets, and certificates sold much better than complicated Latin or Greek treatises. Books were becoming more accessible and tailored to readers’ interests, not just scholarly elites.

What Holds Back Mass Production Before the 15th Century?

It boils down to three main obstacles:

- The market wasn’t ready. Literacy was low, so few buyers existed for mass-produced books.

- High production costs. Vellum was pricey, and scribes’ skilled labor was slow and expensive.

- Technological limits. Early printing attempts—woodblocks, single scribes—were ineffective for truly mass production.

Once paper spread, the market grew, and Gutenberg’s movable type answered the call for efficient printing, the pieces fell naturally into place.

Lessons From History: Why Timing Is Everything for Invention

Looking back, the delay in inventing the printing press is less about human slack and more about context. Inventions need a cocktail of need, technology, and market. Without sufficient buyers, no one wants to invest millions into risky innovation. Without cheaper materials, costs remain prohibitive. Without better tools, production can’t scale.

The printing press story teaches us how gradual, systemic changes—like rising literacy, paper availability, and institutional reforms—create fertile ground for breakthroughs. Gutenberg’s press didn’t jump out of a vacuum; it emerged right when society was ripe for it.

So What’s the Takeaway Here?

If you ever wonder why some ideas take ages to appear, remember this: inventors don’t just build things because they *can*. They build things because the world *needs* them, and because there’s a market to support the effort.

Had someone dropped a printing press in 1300, it would have been a dazzling but expensive curiosity with few buyers. By 1450, thanks to cultural shifts, improved materials, and technological ingenuity, the printing press changed the world forever.

Reader challenge: What current technologies might you think are ahead of their time, waiting for the right mix of market and need? Keep an eye on where demand and innovation collide—you might just spot tomorrow’s printing press!