The Maginot Line was a good strategic idea based on the particular circumstances France faced in the interwar period, but it was undermined by political, geographical, and operational factors beyond the fortifications themselves. It was neither a fundamentally flawed concept nor a mere defensive wall doomed to fail by design. Instead, it served as a force multiplier that supported France’s broader military strategy of mobilizing mobile forces and channeling the German advance through Belgium. The eventual failure owed more to its limited extension, external constraints, and wider strategic missteps than to the Maginot Line concept itself.

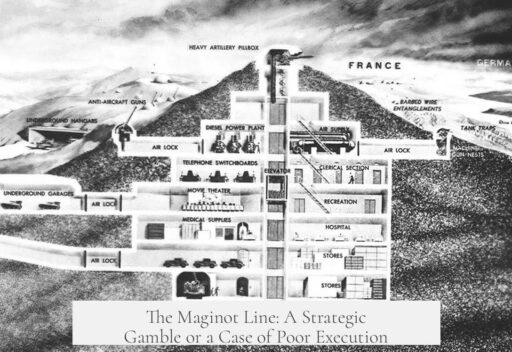

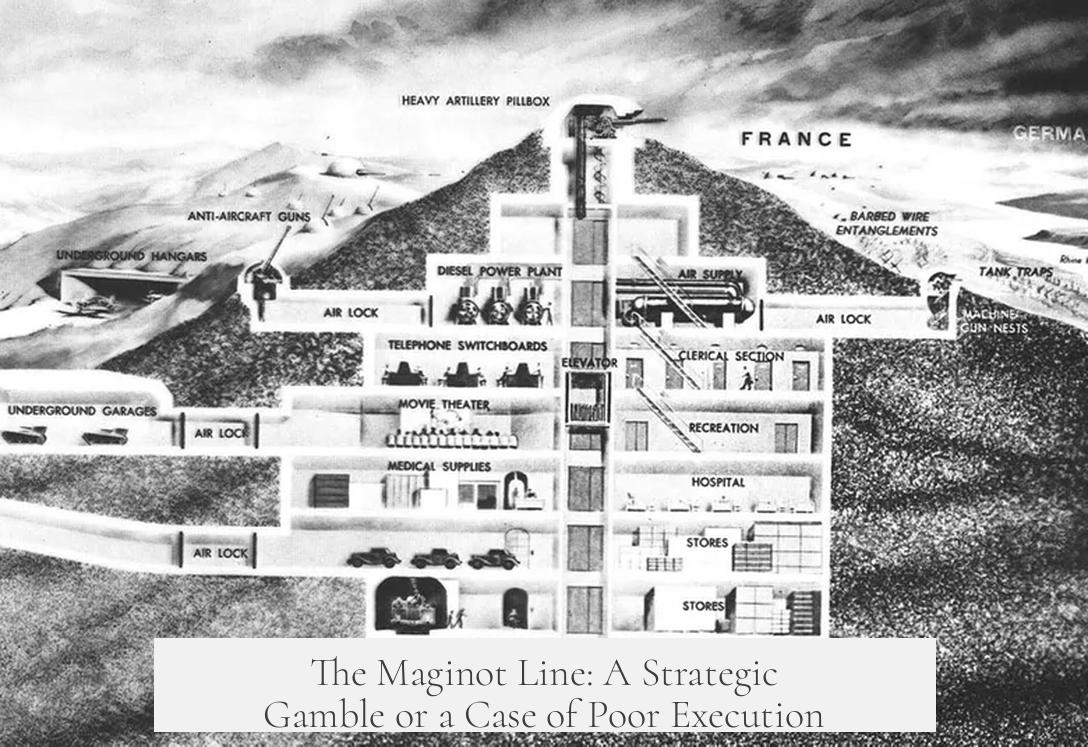

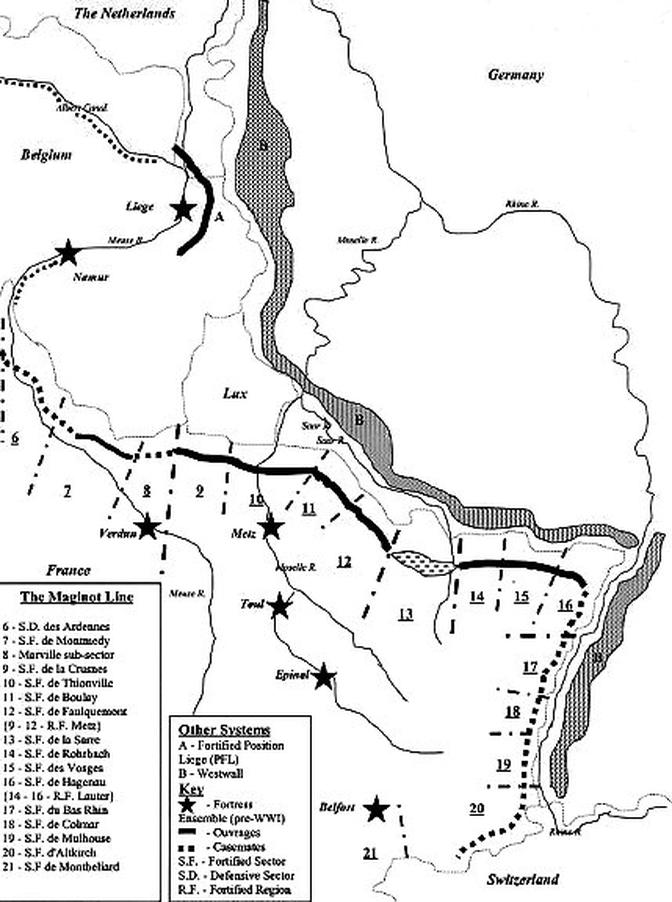

France invested about 2-3% of its military budget into constructing the Maginot Line, a network of fortifications along its border with Germany. This investment reflected a carefully considered strategic aim rather than wasted spending. The line was designed to screen the border, enable French forces to mobilize properly, and concentrate action in Belgium where the French army’s maneuver elements could counterattack. It allowed France to secure the Franco-German border with roughly only 15% of its available troops, freeing manpower for mobile operations elsewhere.

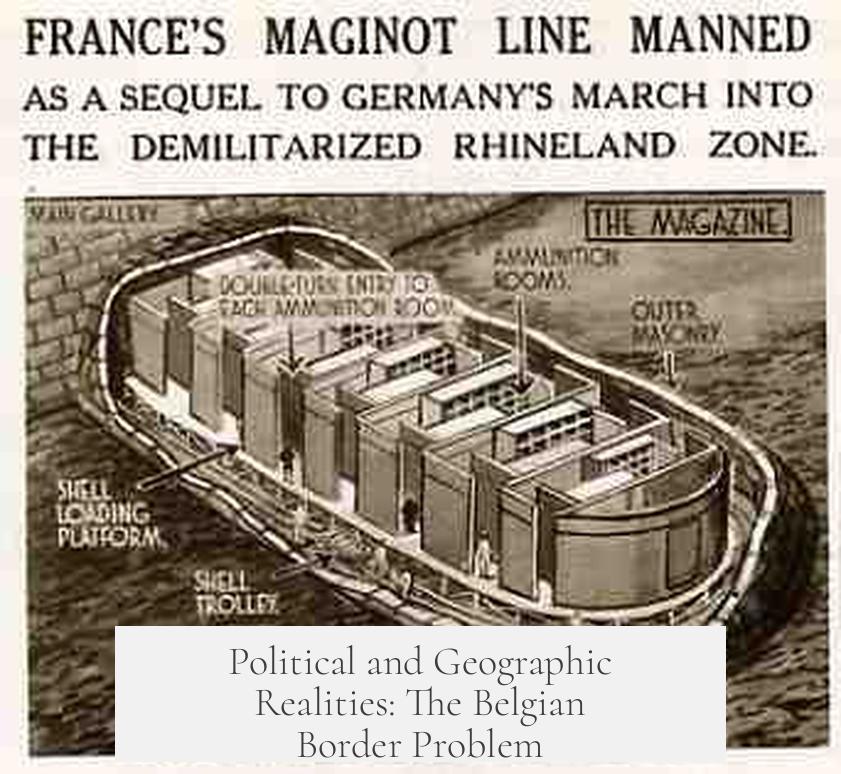

The Maginot Line’s limitations primarily arose from the political and geographic landscape. France considered extending the fortifications along the Belgian border but rejected this plan due to Belgium’s insistence on neutrality and refusal to allow French fortifications on its soil. France even offered to finance defenses in the Ardennes region, yet Belgium declined. The terrain along the Franco-Belgian border posed significant challenges. Open fields, intersecting rivers, a high water table making underground works impractical, and a heavily industrialized area made fortification costly and disruptive to vital French industry.

North-Eastern France contained the country’s key industrial and resource centers. Up to 90% of the textile industry, all automobile and aircraft production, and nearly 75% of coal and iron ore production were in this region. France’s strategy focused on moving the battle into Belgium to keep these economic resources safe and delay conflict within France’s heartland. This approach was formalized as Plan D (the Dyle Plan), aiming to hold a line along the Dyle river inside Belgium rather than the border. The idea was to buy time for allied assistance.

The French military leadership understood that no fortifications could guarantee absolute protection. They accepted that any defensive line could be broken under a sufficiently powerful attack. One key lesson from history was the rapid collapse of Belgian forts at Liège during World War I and experiences around Verdun, which demonstrated the vulnerability of isolated forts in open terrain to concentrated artillery and air bombardment. This awareness meant the Maginot Line was never conceived as an impregnable barrier but as a means to shape enemy movements, protect vital areas, and force the enemy into less favorable terrain.

Strategic manpower constraints shaped the defensive posture significantly. France’s population of about 40 million limited mobilization capacity compared to Germany’s roughly 60 million, which meant France had fewer soldiers available. Defending a longer border along Belgium would stretch French forces thin. The involvement of Belgian and Dutch armies was essential to mitigate this imbalance. The Maginot Line helped by shortening the front line that French troops had to cover.

Regarding mobile warfare, while common criticism holds that France failed to understand the evolution of mechanized combat since World War I, French forces were quite substantial in mechanized divisions. France possessed seven motorized infantry divisions, five mechanized cavalry divisions, and several heavy and medium armored divisions comparable to German Panzer divisions. The difference lay less in capability and more in political, social, and economic challenges that hindered coordinated operational use of these forces.

In fact, French armor doctrine envisaged these tank divisions for breakthrough operations similar to German strategies. They also had specialized tank battalions supporting infantry, deployed at the army and corps levels. The failure to exploit this mechanization effectively related more to command and control issues, miscommunications, and leadership choices than to the Maginot Line strategy itself.

Ultimately, the Maginot Line was a sound strategic concept crafted to suit France’s geopolitical situation and military limitations. Its failure in 1940 cannot be solely blamed on the design or employment of the fortifications. External factors, such as diplomatic restrictions on Belgium, difficult terrain for border defense, concentration of industry in vulnerable areas, and operational shortcomings in mobile warfare, contributed significantly.

- The Maginot Line was a carefully chosen force multiplier, not a standalone defense.

- Political limitations, especially Belgian neutrality, constrained continuous fortification.

- Geography and industrial concentrations dictated strategic deployment choices.

- French strategy relied on moving battle into Belgium to protect national resources.

- Commanders recognized fortifications’ limitations and planned for mobile counterattacks.

- French mechanized forces were comparable in structure to Germany’s, despite criticisms.

- Operational and political failures, not the fortifications themselves, led to defeat.

Was the Maginot Line a Bad Strategy, or a Good Strategy Badly Executed?

So, was the Maginot Line a colossal strategic blunder or merely a brilliant idea that went sideways during implementation? The Maginot Line was a good strategy based on the context of the time, designed thoughtfully, but political and operational constraints hampered its full potential. Let’s unpack the story behind this famous French fortification, because it’s far more nuanced than “just a big wall that failed.”

The Maginot Line has become a symbol of failure—an eyesore of dated defense that the Germans simply bypassed in World War II. That story is popular and catchy, but it misses most of the background, reasoning, and realities France faced when building and relying on this defense line from the 1930s.

Context Is Everything: Why the Maginot Line Made Sense

One of the biggest mistakes people make when judging the Maginot Line is ignoring the historical and political context that shaped French military planning post-World War I. After all, France had just suffered massive casualties and devastation in their industrial northeast. Preserving the core industrial heartland—and the population centres around it—was vital.

Spending just 2-3% of the military budget, France aimed to create a robust defensive barrier along the German border. The logic was straightforward: build a force multiplier to protect crucial regions, buy time for mobilization, and funnel German attacks toward Belgium where French mobile forces would engage them. This wasn’t about making an impenetrable wall; it was about smart deployment.

Sure, hindsight makes it easy to criticize, but at the time, the French command had no illusions. They fully understood that any fortification, no matter how solid, could be broken through by a determined enemy. General Gamelin bluntly admitted this in 1935, noting that front lines could always be breached under sufficient pressure.

Political and Geographic Realities: The Belgian Border Problem

One major thorn in France’s defensive plans was the Belgian border. The French considered extending the Maginot Line along this border, but Belgium insisted on maintaining neutrality, rejecting French offers to help fortify the Ardennes—a dense forest also known for difficult terrain.

Politically, violating Belgian neutrality was a no-go. Strategically, the open fields and intersecting rivers in this area were tough to defend and fortify effectively. Plus, with a high water table and important industrial hubs, digging tunnels and building forts would have been both difficult and disruptive to vital industry.

In other words, building extensive fortifications along the Franco-Belgian border was not practical. This meant France had to push the battle forward into Belgium and defend along the Dyle river in what is called Plan D.

France’s Strategic Aim: Moving the Fight Away from the Industrial Heartland

The heart of France’s strategy was to keep the fighting away from its wealthy and industrial north-east, laced with coal mines and vital factories producing cloth, wool, chemicals, automobiles, and aircraft. This area housed 75% of France’s coal and all of its iron ore, resources no country wanted destroyed or occupied.

Instead of simply defending their own border, the French plan relied on moving the battle into Belgium, hoping to delay and exhaust German forces until Allied help could arrive. This also helped solve manpower issues since France had fewer men and less industry compared to Germany’s larger population and army.

Manpower and Mobility: Busting Myths About the French Military

It’s popular to think the French army in 1940 was stuck in World War I static warfare. But France had developed serious mechanized forces—their equivalent of German Panzer divisions—with seven motorized infantry divisions, five mechanized cavalry divisions, and multiple heavy and balanced armored divisions.

Comparing Germany’s 10 Panzer divisions to France’s mechanized units, the French forces were roughly equal when adjusting for population and military size. They even had independent tank battalions dedicated to infantry support, deployed efficiently in reserves.

The failure wasn’t lack of vision or will to modernize—it boiled down to political, social, and economic obstacles and some operational mistakes not directly linked to the Maginot Line itself.

What the Maginot Line Actually Did: A Force Multiplier, Not a Fortress

The Maginot Line wasn’t meant to be a single massive block of defense. It functioned as a force multiplier, a strategic tool allowing France to guard the Franco-German border with just 15% of its troops. This freed mobile forces to fight more flexibly elsewhere.

This approach addressed the critical problem of France’s limited manpower. Defending a long border—such as the Franco-Belgian one—would have stretched soldiers thin. Relying on Belgian and Dutch forces to cover a broad front was necessary, but ultimately their fortitude and cooperation were uncertain.

So, Why Did It Fail? Execution and External Factors

When Germany invaded in May 1940, they simply bypassed the Maginot Line through the lightly defended Ardennes forest in Belgium, a place French planners assumed was less likely to be penetrated because of terrain. This gamble failed largely because the French underestimated the speed and adaptability of the German blitzkrieg.

Political limitations prevented the extension of the Maginot Line into Belgium. Belgian refusal to allow fortification and France’s reliance on moving the battle outside its borders meant the defense system wasn’t continuous. This gap was a critical operational flaw, not a fundamental flaw in the Line’s concept.

The failure wasn’t the Line itself, but the assumptions about how fast and aggressively the enemy would exploit weak points—and how quickly France and allies would react. The Blitzkrieg showed new dynamics in warfare that were faster, coordinated, and used combined arms effectively.

Lessons from the Maginot Line: Strategic Wisdom and Missteps

The Maginot Line teaches us an important lesson about strategic defense planning under constraints:

- Context matters. France’s strategy was rational given the economic, political, and military limitations of the 1930s.

- Static defenses alone don’t win wars; they work best when integrated with mobile forces and broader strategic plans.

- Political constraints—here, Belgian neutrality—can sabotage even the best military plans.

- Terrain and industrial geography heavily influence military strategy; not all borders are equally defensible.

- Adaptability during conflict is crucial. The French did not anticipate Germany’s rapid and unconventional mechanized assault effectively enough.

Can We Call the Maginot Line a Good Strategy Badly Executed?

This phrase captures the nuance perfectly. The Maginot Line itself was a clever concept, built for limited cost, sound reasoning, and to protect critical French assets. The failures resulted from factors beyond the Line’s design—political decisions, assumptions about Belgian cooperation, and the rapid evolution of warfare tactics.

To label it simply as a “bad strategy” ignores these complexities. It misses the essential fact that France prepared as best it could with what it had. The Line’s partial rigidness was less the issue than the decision to not extend it and the lack of adequate mobile response to Germany’s fast attack.

What Would Have Improved the Maginot Line’s Effectiveness?

- Extending Fortifications: Had Belgium agreed to the French proposal to fortify Ardennes, the Germans would have faced a tougher barrier.

- Better Coordination: Faster and more integrated mobile forces could have bolstered the static defenses.

- Flexible Defensive Postures: Balancing fortification with forward reconnaissance and anti-tank/airborne countermeasures might have blunted the surprise factor of German tactics.

- Allied Military Synchronization: Early coordination and combined operations with British and Belgian armies could have sealed gaps.

In the end, the Maginot Line stands as a monument to interwar strategic thought, a recognition of industrial and military realities, but also a cautionary tale of the limits imposed by politics and evolving warfare.

Final Thought: Don’t Judge a Line by the Battle It Missed

The Maginot Line wasn’t a failure by itself—it was a piece of a larger strategic puzzle. It was a defense carefully tailored to protect vital French interests while buying time and manpower for a mobile defense in Belgium. The rapid German maneuver around it exposed vulnerabilities not in the Line’s design, but in how strategy was enforced and how the broader war was fought.

So next time you hear the Maginot Line described as “a worthless wall,” remember: it was a good strategy poorly executed, tangled in the messy realities of politics, geography, and rapid military innovation.