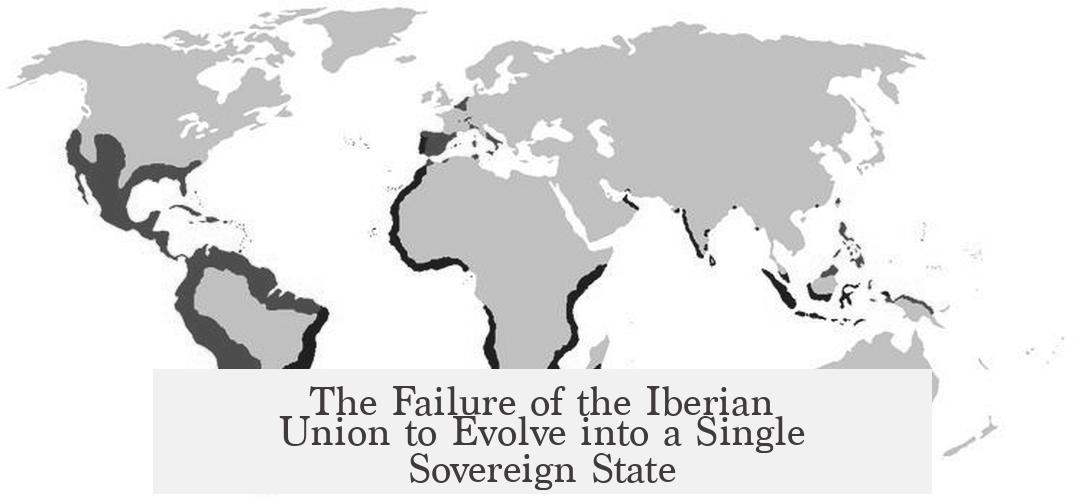

The Iberian Union did not transform into a single state like the union of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon because it remained a composite monarchy—composed of distinct kingdoms with separate laws, privileges, and political cultures. This arrangement limited centralized authority, compounded by local resistance, geographic distance, economic disparities, and Portuguese dissatisfaction, preventing full political integration.

The union established by Isabella and Ferdinand in 1469 is often mistaken as the creation of a centralized Spanish state. However, historians characterize it as a composite monarchy. Instead of merging into one polity, the marriage united the crowns of Castile and Aragon under one monarch who ruled multiple distinct kingdoms. Each kingdom retained its own legal system, privileges, and institutions.

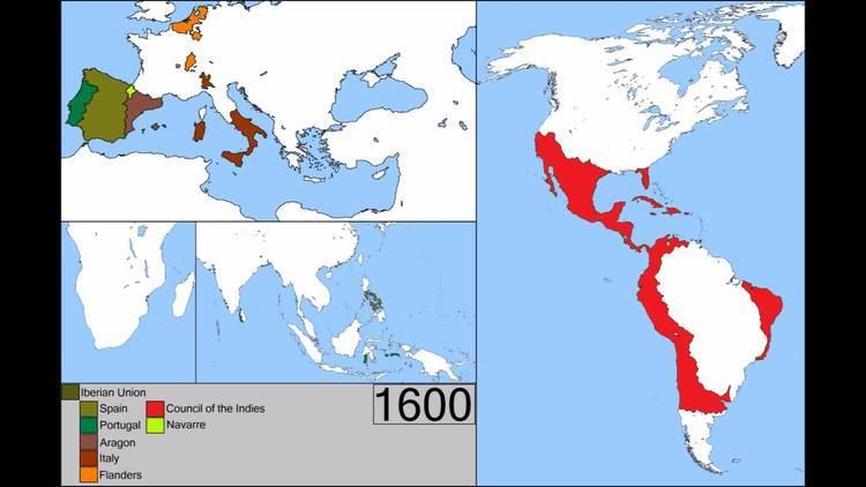

Philip II’s Iberian Union (1580–1640), uniting Spain and Portugal under a single monarch, maintained this composite structure. Philip II was simultaneously King of Spain, Portugal, and other territories, but none of these kingdoms were integrated into a single political entity.

- Each kingdom, such as Castile, Aragon, and Portugal, kept separate laws and legislative bodies.

- Monarchs had to negotiate regularly with local elites and respect regional privileges.

- This system prevented monarchs from imposing centralized control across all realms.

The monarch’s role often became that of an absentee ruler. The geographic spread of the Habsburg empire, including possessions across Europe and overseas, made personal oversight difficult. The monarch’s presence or attention was often focused elsewhere rather than in each kingdom.

Political elites in each kingdom frequently resisted fiscal and military demands made to support Habsburg imperial wars, especially when these burdens affected them unequally. Castile, with a weaker Cortes, provided more subsidies and soldiers. In contrast, Aragonese and Portuguese nobles negotiated fiercely to limit their contributions.

Portugal, in particular, exhibited significant discontent under the Iberian Union. The Portuguese nobility felt marginalized at the Madrid court. Spanish advisors (valido) were mainly Castilian grandees, and Portuguese interests were often subordinated to Castile’s global priorities. Spain focused resources on its Atlantic empire, while Portuguese overseas territories received less support.

This perceived Spanish dominance caused frustration among the Portuguese, who saw their crown as an intrusive entity rather than an equal partner. The rivalry and lack of mutual trust made efforts at centralization difficult.

Economic disparities aggravated tensions. Peripheral kingdoms like Aragon and Catalonia suffered economic decline as Spain shifted its focus to Atlantic trade. This fueled dissatisfaction among the elites in these regions, who resisted further commitments to Habsburg imperial wars, especially those far from their territories.

Earlier attempts to strengthen centralized rule, such as the Union of Arms under Count-Duke of Olivares during Philip IV’s reign, failed. Olivares aimed to convert the composite monarchy into a more cohesive federation with shared military obligations. However, long-standing political customs of local negotiation and autonomy hindered reforms, and resistance from regional elites stubbornly persisted.

The collapse of the Iberian Union came amid mounting revolts and imperial overreach. Simultaneous uprisings in Catalonia and Portugal in the 1640s strained military and financial resources. Faced with these crises, the monarchy prioritized the Catalan revolt due to the immediate threat from France. Consequently, the Portuguese rebellion entrenched itself, leading to Portugal’s final separation from the union in 1640.

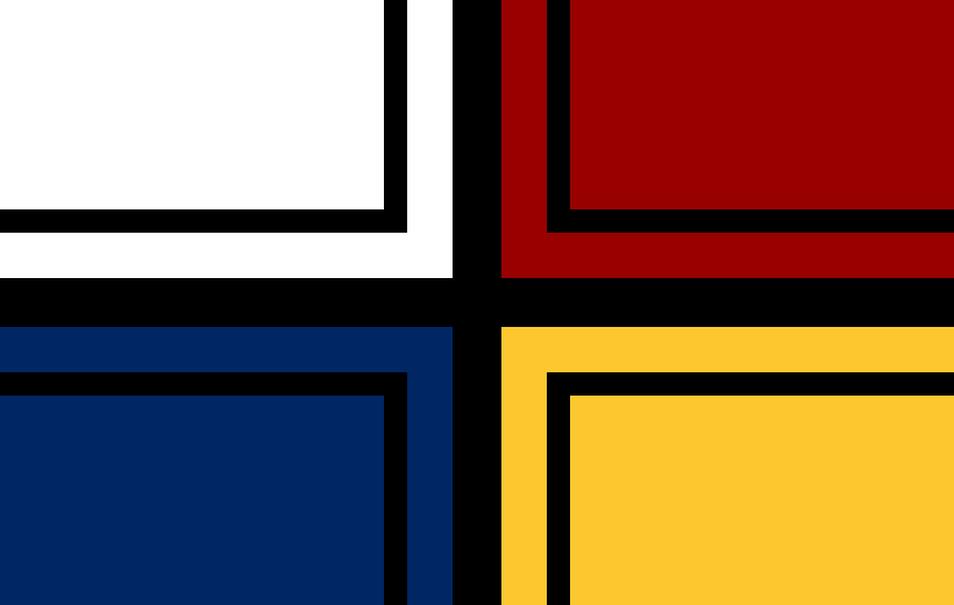

| Factor | Impact on Iberian Union |

|---|---|

| Composite Monarchy | Separate laws and privileges prevented political unification. |

| Local Privileges | Monarchs had to negotiate with distinct political bodies. |

| Absentee Monarchs | Geographic and global commitments reduced centralized control. |

| Portuguese Discontent | Marginalization fueled resistance to union integration. |

| Economic Imbalance | Peripheral regions declined, undermining cohesion. |

| Failed Reforms | Attempts at centralization confronted entrenched autonomy. |

| Revolts and Overstretch | Multiple crises broke the union’s fragile hold. |

In contrast, the union of Ferdinand and Isabella, although not a unitary state in the modern sense, laid the groundwork for a more cohesive Spanish monarchy. It focused on internal consolidation within Iberian kingdoms closely linked geographically and culturally, with fewer external commitments. The later Iberian Union was marked by wider diversity and competing imperial interests that obstructed deeper political integration.

- A composite monarchy governs multiple, distinct kingdoms with their laws intact.

- The Iberian Union maintained regional privileges, preventing state fusion.

- Portuguese elites felt sidelined, fostering resentment toward Spanish rule.

- Economic disparities between kingdoms reduced willingness to unify politically.

- Efforts to centralize failed against entrenched political traditions.

- Simultaneous revolts capitalized on the system’s overstretch and weaknesses.

Why did the Iberian Union not turn into a single state like the union of Isabel I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon did?

The Iberian Union did not transform into a single state like the earlier union of Isabel I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon because it remained a composite monarchy—a collection of distinct kingdoms with their own laws, privileges, and political cultures. Multiple factors, including local resistance, absentee monarchs, economic disparities, and the uneasy Spain-Portugal relationship, blocked political unification.

Let’s unpack this complex story because it’s not just about a royal marriage or political convenience—it’s about how centuries of independent identities and traditions shape the fate of empires.

The Illusion of a Unitary State Under Ferdinand and Isabella

Take a moment to picture Ferdinand and Isabella’s famous marriage. Most people assume they created a single, powerful Spain from the get-go. The truth is far more nuanced. What they formed was a composite monarchy. Think of it as a royal umbrella covering several kingdoms, each operating like its own little universe.

The eminent historian J. H. Elliott calls this arrangement a “composite monarchy.” For example, even though Philip II later ruled Spain as a whole, he was still separately King of Aragon, Castile, Naples, and other realms with distinct laws and privileges. This composite nature means the king was a monarch over many kingdoms, not a ruler of one unified state.

This distinction explains why the Iberian Union, led by Philip II and successors, stayed a patchwork of kingdoms rather than a centralized state like modern countries.

Local Privileges: Ancient Laws and Crown Tug-Of-War

Imagine the king walking into each kingdom, each greeting him with a unique set of rules, customs, and political demands. The monarchs walked a tightrope, always negotiating local privileges instead of imposing direct control.

Castile, for example, had a weaker legislative body called the Cortes, making it easier for the monarchs to pull in taxes and subsidies. But Aragon’s Cortes was tougher negotiator, leading to drawn-out talks for just a small amount of funding.

Maintaining local laws and traditional rights prevented the rise of a unitary authority. Each kingdom jealously guarded its autonomy, creating a political mosaic instead of a nation-state. The monarch couldn’t just decree a law for all Iberia because these privileges were like ancient contracts to the local elites.

The Dilemma of Absentee Monarchs and Global Ambitions

Here’s a twist: The Habsburg monarchs, ruling over a vast empire, couldn’t be everywhere at once. They were often absent, especially as their territories spanned continents, from Europe to the Americas and Asia.

This distance stretched the system thin. Local elites often wondered why they should bleed and pay for faraway wars and distant monarchs they hardly saw.

Absentee rulers meant less centralized enforcement and local leaders with growing independence. It’s like trying to manage a household while vacationing abroad—you lose grip on the day-to-day.

Portuguese-Spanish Relations: A Union Without Love

The Iberian Union married Portugal and Spain under the same monarch, but it was hardly a match made in heaven. Philip II initially hesitated to claim the Portuguese throne, aware of old hostilities between the two nations.

Portuguese nobles rarely made it into the king’s inner circle at the Escorial, which was dominated by Castilian favorites. Worse yet, Madrid prioritized Spanish overseas investments, leaving Portuguese interests starved of attention and resources.

This created resentment on both sides. Madrid viewed Portugal as an unreliable junior partner, while Portuguese elites saw Spain’s dominance as intrusive.

Without mutual enthusiasm, the union resembled an uneasy roommate situation rather than a harmonious partnership. Portugal carried suspicion toward integration while Spain was reluctant to cede influence.

Economic Shifts Widening Regional Gaps

By the late 1500s, an economic tide was rising that favored Castile and Atlantic trade routes. Meanwhile, traditional powerhouses like Aragon and Catalonia experienced economic decline.

Those peripheral kingdoms bore heavy burdens to fund endless wars in Italy and the Low Countries, while watching their own domains fall behind economically.

Imagine being asked to chip in for a party you don’t really care about, while seeing others have the best seats and resources—resentment brewed easily.

The Clash with Political Culture: Attempts at Centralization

Recognizing these weaknesses, the Count-Duke of Olivares tried to reform the system. His “Union of Arms” sought a collective defense pact under Philip IV, redistributing military responsibilities among the kingdoms.

But this was like asking a village used to self-rule to suddenly act as a single, centralized army. The entrenched political culture of local autonomy and negotiated privileges made reforms tough to implement.

The Iberian political landscape was rooted in centuries of independent traditions, so Olivares’s well-intended reforms barely took hold.

Revolts and Overstretch: The Final Nail in the Coffin

The 1640s were a cataclysmic decade for the Iberian Union. Simultaneous revolts erupted in Catalonia and Portugal at the worst moment imaginable for Philip IV’s reign.

Spain’s empire was overstretched. Facing a serious French threat, the king focused Castilian forces on Catalonia. By the time that revolt simmered down, Portuguese rebels dug in deep and couldn’t be dislodged.

Additionally, Madrid’s currency policies sparked inflation, further straining royal finances. When elite cooperation falters and resources run thin, the glue holding composite monarchies together weakens, often irreparably.

Unsurprisingly, the Iberian Union dissolved, marking a definitive end to hopes of transforming the composite monarchy into a unitary state like the earlier Castile-Aragon example.

Takeaways: History’s Complex Recipe

The story shows us that royal marriages alone don’t make centralized nations. The Iberian Union’s failure to become a single state is a textbook example of how local identities, legal pluralism, economic imbalances, and political cultures shape historical outcomes.

It also reminds us that empires built on many crowns and privileges need careful balancing acts between unity and autonomy. When those balances tip, fragmentation follows.

In short, while Isabel and Ferdinand created a composite but relatively stable monarchy, the Iberian Union’s larger scale, diverse kingdoms, and competing ambitions doomed it to remain many parts under one crown—not a single united Spain.

Curious about composite monarchies?

- Think of them as families owning several houses, each with its own rules and tenants, sharing a landlord but resisting shared governance.

- Trying to centralize too fast often sparks unrest—familiar story in empires.

- The Iberian Union challenges the idea that dynastic union equals nation-state. Instead, it shows how history prefers patchwork quilts over clean seams.

So when you hear the phrase “one Spain,” remember it took centuries and was far from straightforward. The Iberian Union is history’s way of reminding us: monarchy is more than crowns—it’s cultures, laws, and deep-rooted identities.