Disembowelment, or seppuku, becomes the favored method of ritual suicide in Bushido culture due to its deep cultural symbolism and the values it represents. Unlike other forms of suicide, seppuku physically exposes the stomach, or hara, which holds great significance in Japanese tradition. The hara is considered the seat of the heart and soul. This contrasts with Western beliefs that associate the heart as the center of the soul. Displaying the empty or wounded hara communicates purity and honesty. Through this act, samurai prove they harbor no deceit or “two hearts.”

The ritual nature of seppuku ensures it is performed with dignity and control, key elements of Bushido ethics. Alternative methods, such as poisoning or drowning, lack public transparency and clear symbolism. Bullets or bludgeoning methods contradict the discipline expected of a samurai’s death. Additionally, seppuku requires visible and undeniable courage because it is intensely painful. This endurance resonates with the Bushido ideal of bravery in life’s final moments.

The ritual traditionally unfolds in two stages. Initially, the samurai disembowels himself, demonstrating resolve through pain. Then, a trusted assistant quickly performs decapitation to end suffering, maintaining honor. In some late cases, the samurai themselves may deliver the fatal cut to their throat after the initial act, showing ultimate self-control.

Seppuku’s popularity is thus rooted in:

- The cultural reverence for the hara as the inner self

- Its role in visibly proving honesty and regaining lost honor

- The demonstration of courage through a painful, public act

- The ritualized, disciplined procedure that aligns with Bushido principles

This method eloquently combines spiritual significance, honor restoration, and the warrior’s bravery—features less evident in alternative forms of ritual suicide.

| Reason | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Cultural Meaning of Hara | Stomach seen as soul’s seat; reveals true character |

| Restoring Honor | Disembowelment exposes purity; shows no betrayal |

| Courage Display | Painful act requiring bravery, reflecting Bushido values |

| Ritual Constraints | Needs to be public, clear, and dignified; excludes poison, hanging, drowning |

| Procedure | Often two-step: self-disembowelment followed by decapitation |

- Hara symbolizes heart and truth in Japanese culture.

- Seppuku visibly confirms a samurai’s honesty and honor regeneration.

- Its painful nature enables a courageous final demonstration.

- Chosen because it fits public, ritualized settings unlike other methods.

- The two-stage process ensures both endurance and dignified death.

Why Was Disembowelment So Popular in Bushido Culture, Opposed to Any Other Type of Ritual Suicide?

The popularity of disembowelment, or seppuku, in Bushido culture roots deeply in the symbolic and spiritual significance the Japanese attached to the stomach area, coupled with the societal values of honor, courage, and ritual respect. Unlike other suicide methods, seppuku was an intentional, public, and highly formalized act designed to communicate purity of heart and strength of character.

To truly grasp why disembowelment stood out amid various conceivable options, it helps to unpack the cultural context and ritual framework that made seppuku unique and revered among samurai.

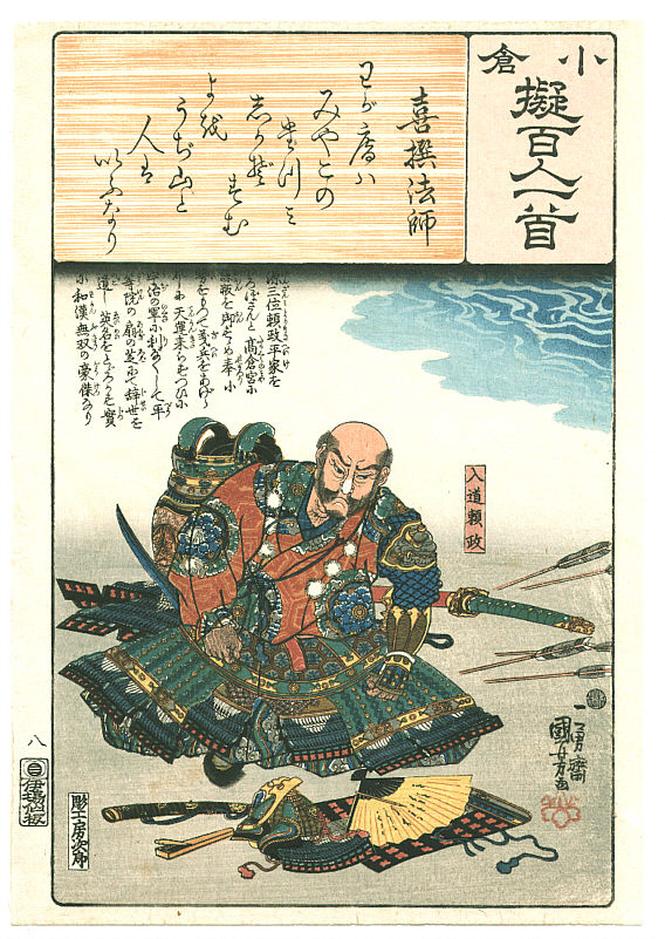

The Sacred Heart of the Samurai: Understanding the Role of the Hara

In Japanese culture, the concept of “hara” (腹) goes beyond the simple stomach. It’s the seat of one’s courage, spirit, and true feelings—a stark contrast to Western ideals that associate the heart as the soul’s home. This distinction isn’t just poetic; it shaped how samurai thought about life, death, and honor.

Expressions like “show me what’s in your hara” mean “reveal your true intentions.” This is crucial when we consider why the act of cutting open the belly during seppuku carried such significance. It was the ultimate exposure of one’s inner truth and purity—cutting open the hara was like baring one’s soul.

Seppuku: A Rite to Regain Honor and Prove Purity

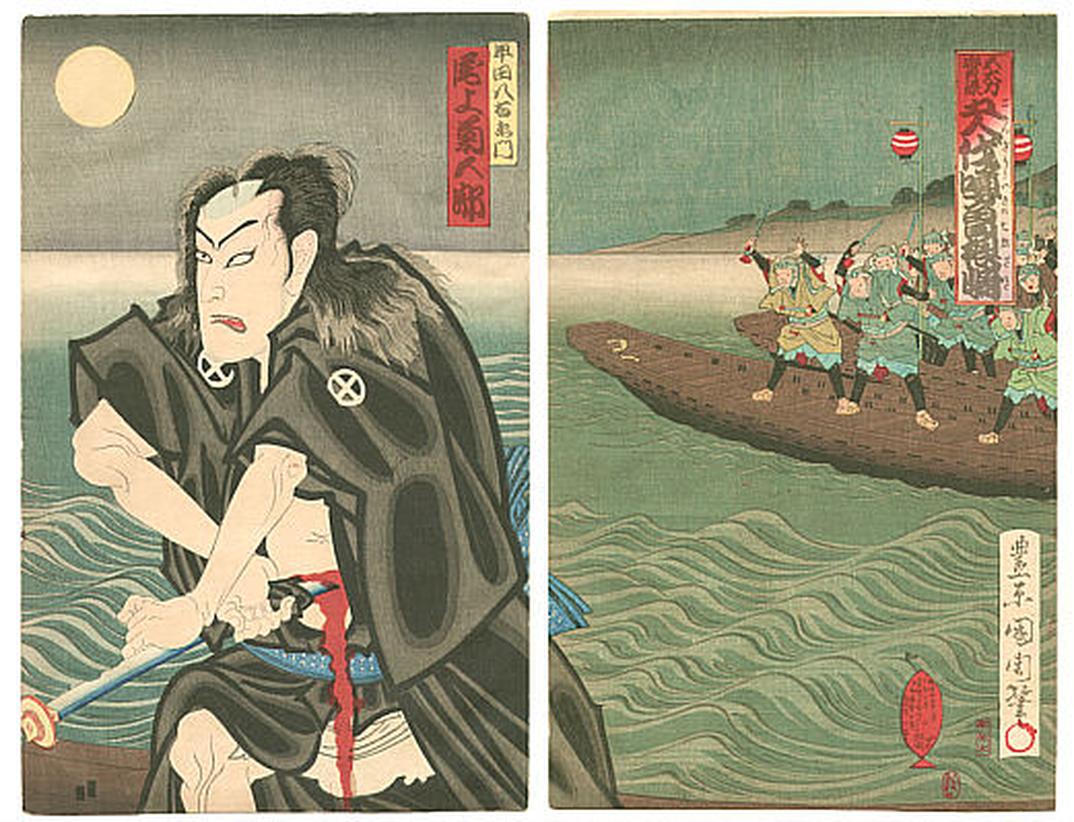

When a samurai performed seppuku, it wasn’t simply a death scene. It was a profound statement. Opening the belly symbolized that one did not harbor deceit—“no two hearts,” as it were. The samurai willingly exposed the very place believed to hold their sincerity and integrity to the world.

This dramatic gesture served to clear any suspicion or shame, showing everyone that the samurai died honorably and with a clean conscience. It was an act of restoring order in a society that prized social standing and reputation.

Courage Amplified Through Pain: Why Seppuku Demanded Respect

Seppuku was excruciatingly painful. This wasn’t accidental or sadistic—it was intentional. The Bushido code celebrated courage, not stealth or quick escapes. By enduring this brutal ritual, the samurai showed the ultimate bravery. Many other suicide methods did not offer this public stage to display grit under unbearable pain.

This wasn’t about suffering for suffering’s sake but proving that even in death, the samurai maintained discipline and bravery.

Why All the Other Methods Didn’t Make the Cut

Sure, a samurai could have chosen bullets, poison, drowning, hanging, or even blunt force trauma, but each was impractical or unfit for ritual purposes.

- Bullets: When seppuku originated, guns weren’t a thing yet. Even after firearms appeared, they remained unsuitable for ritual suicide, too quick and lacking ceremony.

- Poison or Overdose: These methods lack visibility and spectacle. Seppuku demanded a public, unmistakably honorable end.

- Drowning, Falling, Hanging: These could happen only rarely on battlefields, lacked formality, and left too many uncertainties about a samurai’s control over death.

- Bludgeoning: Slamming one’s head with a rock might seem disrespectful, chaotic, and desperate—not in line with the samurai’s calculated taken control of their death narrative.

So, seppuku wasn’t just a choice—it was THE choice for ritual death, perfectly aligned with Bushido values.

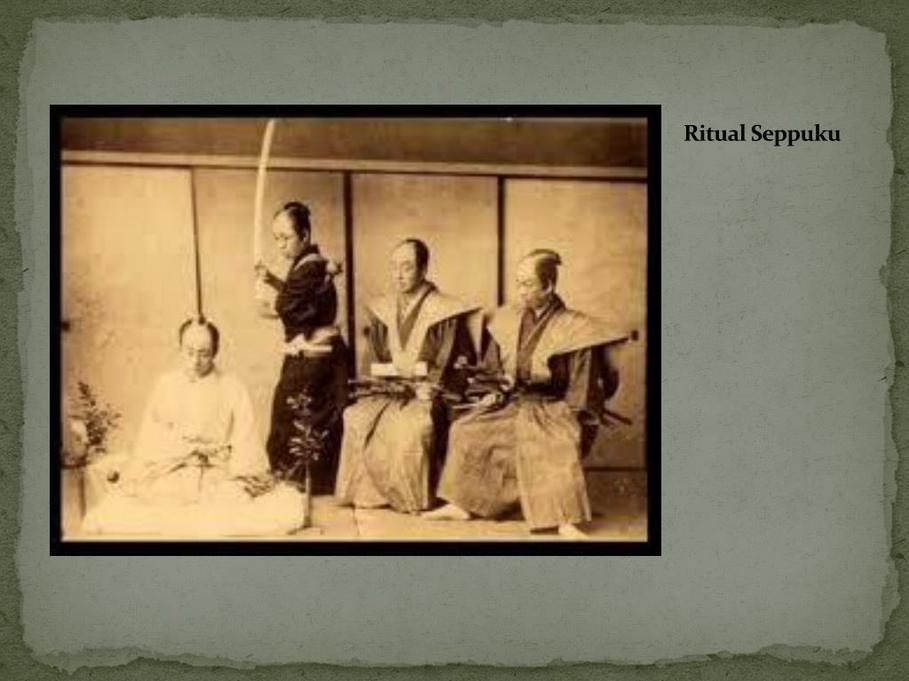

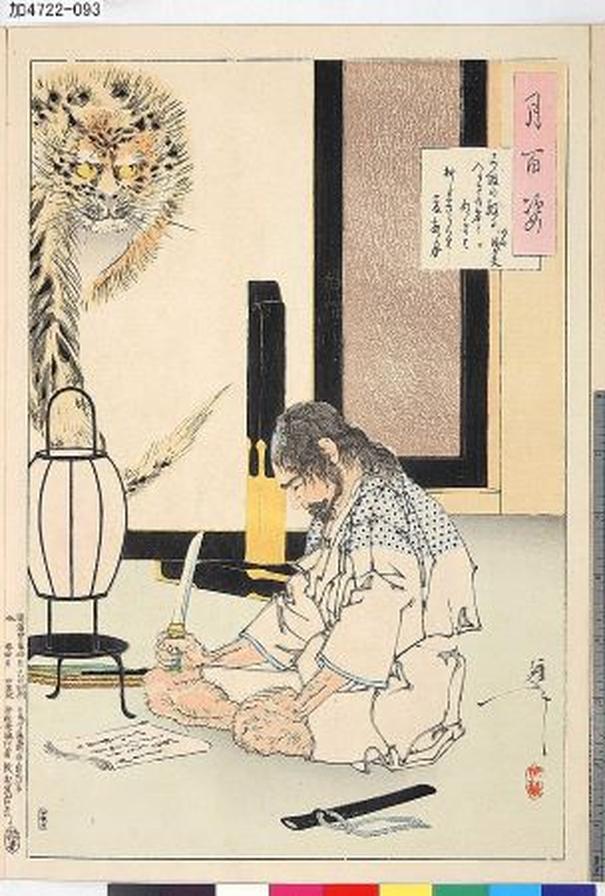

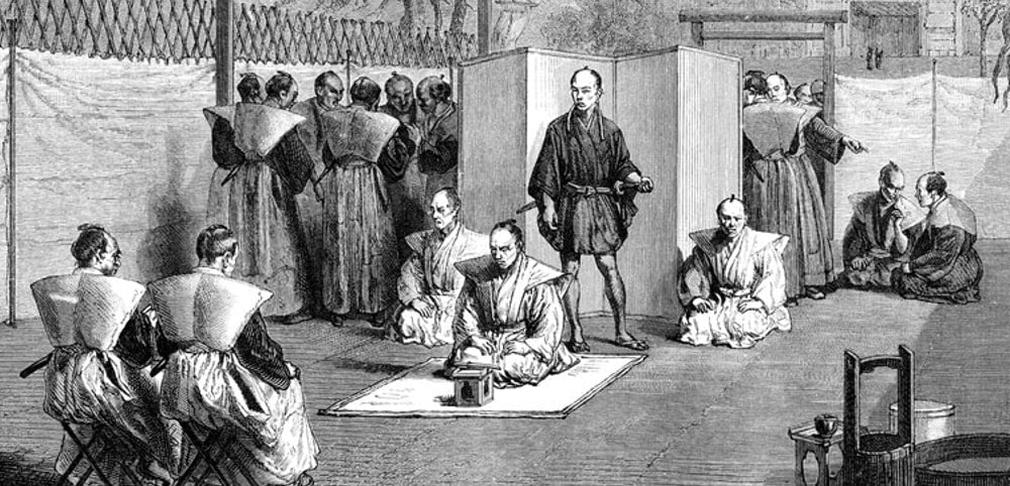

The Ritual Performance: Two Stages of Seppuku

Most people know about the stomach cutting part, but there’s an often-overlooked second phase: decapitation. After disemboweling, the samurai’s second—a trusted companion—would swiftly remove the head. This part prevented prolonged suffering and maintained a dignified end.

Imagine the tension: the samurai faces death with poised resolve, knowing a friend is waiting to grant a swift release. This two-step death process added layers of meaning, trust, and shared honor.

Late 19th Century Shift: The Samurai’s Final Autonomy

By the late 1800s, some Western accounts report that samurai sometimes forewent the second person. They performed self-decapitation after disembowelment. Talk about ultimate control!

This evolution reflected changing times while maintaining the same ritual symbolism. Even with new methods, samurai remained committed to showing pure courage and honor in death.

Wrapping It Up: What Makes Seppuku a Cultural Icon?

Seppuku’s popularity lies in the deep cultural root of the hara, the symbolic act of revealing purity, the demand for courage through pain, and the strict ritual that validated honor in death. No other method matched the respect, control, and symbolism that seppuku embodied.

In a society where public perception and honor dictate legacy, death wasn’t just an end—it was a final message. Seppuku wrote that message in flesh and spirit.

Got questions or curious about ritual symbolism in other cultures? Share your thoughts below—let’s dive into the fascinating world of honor, duty, and death!

Why was the stomach (hara) targeted in seppuku rather than other body parts?

The stomach, or hara, held special meaning in Japanese culture. It was seen as the seat of one’s spirit and honesty. Cutting the stomach symbolized showing one’s true heart and purity.

How did seppuku serve to restore a samurai’s honor?

By disemboweling himself publicly, a samurai demonstrated he had no hidden motives or betrayal. This act proved his loyalty and helped regain lost honor.

Why were other methods like poison or hanging rejected for ritual suicide?

Seppuku required a clear, honorable, and public demonstration. Poison and hanging lacked visible, immediate suffering or dignity. Other methods didn’t fit the formal and controlled nature of the ritual.

What role did courage play in the choice of disembowelment as a suicide method?

Disembowelment was very painful and difficult. Choosing seppuku allowed the samurai to display bravery and control over death, which were key Bushido values.

Why was decapitation sometimes part of the seppuku ritual?

After cutting the stomach, a trusted person often decapitated the samurai to end suffering swiftly. This showed honor and respect, maintaining dignity in death.