The cotton gin helped maintain and expand slavery in the United States by significantly improving cotton processing efficiency, but it did not singlehandedly save slavery. Rather, it worked together with advances in cotton breeding, expansion into new lands, and economic shifts to sustain and grow the slave-based cotton economy.

The cotton gin, invented by Eli Whitney in 1793, was a machine designed to remove seeds from cotton fibers quickly. Before this, separating cotton fibers from seeds was very slow and labor intensive. The cotton gin made short-staple cotton production viable on a large scale by increasing the speed and reducing the cost of processing the fiber. This boosted demand for cotton and made cotton plantations highly profitable, which in turn increased the reliance on enslaved labor. However, this invention was just one piece of a complex agricultural and economic puzzle that kept slavery entrenched.

Before the widespread use of the cotton gin, only certain types of cotton, such as those grown on the Carolina Sea Islands, could produce fibers suitable for the textile industry. These varieties grew in limited areas, restricting cotton expansion. Some upland varieties that existed were poor quality and took a lot of labor, reducing profitability. Around 1800 to 1820, new cotton breeds and hybrids emerged, especially in the Mississippi Delta. These hybrid varieties were better adapted to upland soils, easier to pick and deseed, and yielded higher quality cotton.

This development is significant because it allowed cotton cultivation to spread beyond limited coastal areas into vast interior lands. The southern United States saw an expansion of cotton territory into central Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, and later into areas opened up by the forced removal of Native American tribes. The availability of suitable cotton seeds was critical for turning these new lands into productive plantations.

At the same time, the rapid rise of cotton demand was fueled by the Industrial Revolution and the growth of textile mills in Britain and the northern U.S. However, early 19th-century cotton production suffered setbacks due to diseases like cotton rot. These threats compelled planters and breeders to develop new hybrids better resistant to diseases and adapted to different climates. The spread of Mexican cotton seeds, which were hybridized extensively, was especially important. A cotton breeder in Mississippi ranked these seeds as second only to the cotton gin in their influence on the southern cotton economy.

Economically, the cotton gin reduced the labor required to clean cotton, but it also led to an expansion in cotton acreage and production. This paradoxically increased demand for enslaved field laborers to plant, tend, and harvest the greater cotton fields newly accessible with improved seed varieties. Therefore, the cotton gin made cotton processing faster but did not reduce the need for slaves; rather, it intensified their use by allowing plantations to expand.

- The forced removal of Native American populations opened new lands for cultivation.

- New cotton hybrids allowed successful cultivation in upland and previously marginal areas.

- Rising textile demand from industrial growth amplified the economic incentives for cotton.

Research into slave productivity and economics shows that the expansion of slavery depended on many factors beyond technology. Rising slave prices, the profitability of cotton plantations, land policies, and geopolitical shifts all played roles. The cotton gin’s contribution was crucial but intertwined with these broader trends.

“There’s a lot more to just the cotton breed part of why US slavery boomed in the 1800s. And that is just one factor of many besides the cotton gin that ‘saved’ US slavery.”

The cotton gin is often presented in simplified narratives as the single invention that saved slavery by making cotton profitable. The truth is more layered. The cotton gin catalyzed a surge in cotton production efficiency. Meanwhile, new cotton breeds opened up large tracts of land to cotton farming, and economic forces from industrial textile demand supported expansion. Slavery’s persistence owed to this complex interaction rather than the cotton gin alone.

- The cotton gin improved cotton processing speed and efficiency.

- New cotton varieties and hybrids allowed cultivation in wider regions.

- Expansion of cotton acreage required more slave labor despite efficiency gains.

- Removal of Native Americans created new farmland for cotton cultivation.

- Industrial demand sustained profitability, incentivizing expansion of slavery.

- Economic, agricultural, and geopolitical factors combined to prolong slavery’s existence.

Understanding how the cotton gin “saved slavery” requires situating it in this broader context. It was essential but only one of multiple factors that kept slavery profitable and widespread in the antebellum United States.

How Did the Cotton Gin Save Slavery? A Closer Look at the Complex Truth

The cotton gin did not single-handedly save slavery, but it played a key role as one of several crucial factors that kept the institution profitable and expanding during the 19th century. That’s the short answer, but the story is far more tangled than the common tale most history books tell.

The cotton gin, invented by Eli Whitney in 1793, is often hailed as the miraculous machine that bolstered slavery by dramatically speeding up the seed-removal process from cotton fibers. It’s easy to imagine this device as the savior of slavery, transforming a tedious task into a swift operation and making cotton cultivation immensely profitable. But the reality is that it’s just part of a much bigger picture.

More Than Just a Machine: The Unsung Role of Cotton Varieties and Hybrids

Before celebrating Whitney’s invention too much, we have to understand that the cotton gin’s effectiveness depended heavily on the cotton itself. Not all cotton is created equal. Early American varieties were limited and tricky to grow outside specific areas like the Carolina Sea Islands and the Mississippi Delta. These “Sea Island” cottons were high quality and easier to handle but didn’t thrive inland.

On the other hand, “upland” cotton varieties, available by the late 1700s, grew well in places like Georgia or Alabama but came with big downsides: lower quality and labor-intensive harvesting. The cotton gin was certainly more economically vital to these upland varieties because it reduced the labor—but it didn’t make the plant itself easier to cultivate or expand.

Cotton Breeding & Expansion: The Silent Heroes of Slavery’s Boom

Between 1800 and 1820, Southern agricultural innovation exploded. Scientists and farmers cross-bred cotton types, introducing hearty new hybrids ideal for expanding cotton cultivation. Mexican cotton seeds arrived and became a game changer—they thrived in upland soils and produced better cotton, boosting yields and profits. One Mississippi cotton breeder even ranked this development as nearly as important as the cotton gin itself.

Here’s the catch: without these new breeds, the cotton gin wouldn’t have had enough suitable cotton to process on a large scale. The industrial revolution’s demand for cotton textiles hit a snag when fungal diseases and “cotton rot” blighted crops. This crisis spurred more breeding efforts, leading to hybrid varieties better adapted to the increasingly opened lands following Native American removals.

The Land Factor: More Room to Grow (and Enslave)

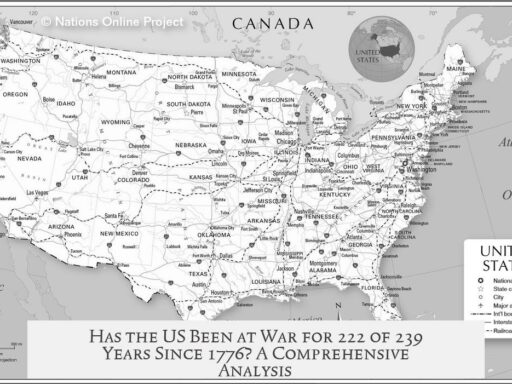

A crucial, often overlooked part of the slavery boom is land availability. As Native American nations were forcibly removed to Oklahoma, vast tracts of fertile land became accessible for cotton farming. This expansion was not thanks to the cotton gin but to violent geopolitical moves that facilitated plantation spread.

These new lands, combined with the new hybrids and cotton gin efficiency, created a perfect storm that fueled the rapid growth of the slave-based cotton economy well into the 1830s and beyond.

Economics and Productivity: The Bigger Picture

It’s tempting to attribute the persistence of slavery to the cotton gin alone, but economic studies tell a more nuanced story. Research, including the paper “Wait a Cotton Pickin’ Minute! A New View of Slave Productivity,” highlights fluctuating slave prices, changing productivity, and broader economic forces at play.

The cotton gin reduced the seed removal bottleneck but wasn’t enough to sustain or expand slavery by itself. You have to layer in agricultural innovation, land expansion, industrial demand, and slave labor economics to grasp why slavery not only survived but grew.

So, How Did the Cotton Gin Save Slavery?

It helped tremendously by cutting processing time and costs, making cotton production more profitable, especially for tricky upland varieties. This profitability supported the value of enslaved labor on plantations tied to cotton harvesting and processing.

But the gin was not a magic wand. Its saving power was **entwined with** agricultural advances, new cotton varieties, significant land acquisitions, economic shifts, and industrial demand. Slavery’s boom was the product of a complex web of innovations and circumstances, not one machine.

A Modern Takeaway

Looking back, we see a lesson in how history often gets simplified. The cotton gin wasn’t the sole hero or villain in the story of slavery—it was a piece in a puzzle where environment, technology, economy, and politics all intertwined. Recognizing that complexity helps us understand how deep and devastating the system of slavery truly was.

Imagine if someone told you the cotton gin was the only reason slavery lasted — you’d miss the tangled roots feeding it. So next time you hear “cotton gin saved slavery,” remember it’s more accurate to say it helped save slavery, **along with many other forces.** What other inventions or policies today might we be over- or underestimating in their impact?

How exactly did the cotton gin impact the profitability of slavery?

The cotton gin made removing seeds from cotton faster, boosting cotton processing efficiency. This cut labor costs and increased output, making cotton plantations more profitable and supporting the slave economy.

Why is the cotton gin not the sole reason slavery expanded?

Slavery’s growth involved more than just the cotton gin. New cotton varieties, hybrids, and more farmland opened by Native American removal all played key roles alongside economic shifts.

What role did new cotton hybrids play alongside the cotton gin?

New hybrids brought better cotton to areas previously unsuitable for growing. These varieties allowed plantations to expand into new lands, increasing cotton production and reinforcing slavery’s economic base.

How did the introduction of Mexican cotton seeds influence slavery’s survival?

Mexican seeds led to hybrids that were easier to grow and process. A breeder called this change second only to the cotton gin, showing how new seeds helped sustain slavery’s profitability.

Did the cotton gin eliminate all labor in cotton processing?

No, it only sped up seed removal from cotton. Picking cotton still required intense manual labor, which kept the demand for enslaved workers high on plantations.