The Byzantine Empire did not have a native knighthood exactly like the Latin knights. Instead, it had a system centered on heavily armored cavalry called the Kataphraktoi and a unique grant system known as Pronoia, which served some comparable social and military functions but differed greatly in structure and political context.

Latin knights are well-known as the backbone of European feudal armies. They commonly received land in exchange for military service. This land was typically hereditary, forming the basis of a decentralized feudal society with local lords wielding considerable independent power.

In contrast, Byzantine heavy cavalry—the Kataphraktoi—served as a formidable military force for centuries. They resembled knights in their role as armored horsemen but operated within a highly centralized imperial system. The Byzantine emperor maintained strong control over military appointments and land rights, unlike the feudal dispersion of power in the West.

The Byzantine political and social structure gave rise to the Pronoia system. Pronoiars, recipients of Pronoia grants, were granted rights to collect taxes or tolls rather than outright ownership of land. These grants were not hereditary for most of Byzantine history and depended entirely on the emperor’s will. Military service and fiscal duties were expected in return for these privileges.

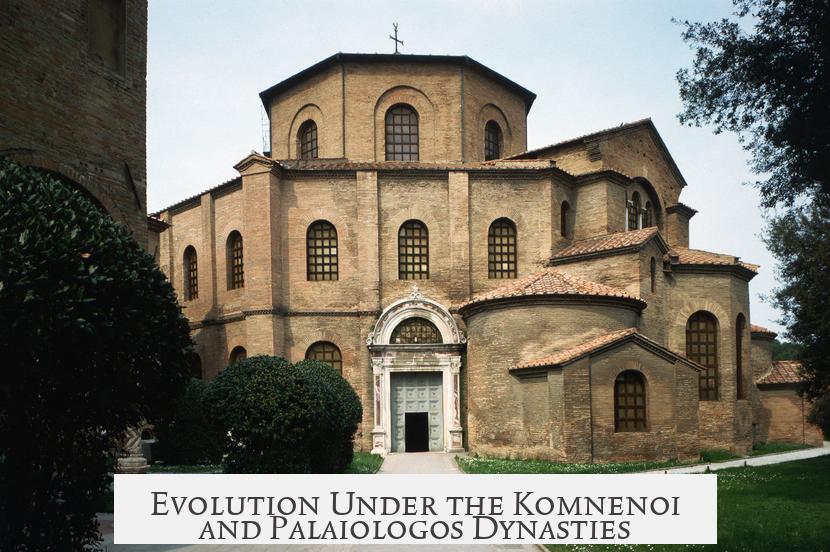

From the 11th to 14th centuries, especially under the Komnenoi and Palaiologos dynasties, Pronoia grants began to evolve. Nobles received land or rights to generate revenue but still under imperial control. Only in the late Palaiologan period did some grants become inheritable, yet even then, the arrangement remained distinct from Western feudalism.

During the Komnenian restoration (circa 1080–1180), the Byzantines also incorporated Latin knights as mercenaries or regular soldiers, highlighting the coexistence but not merging of these martial traditions.

| Aspect | Byzantine Native System | Latin Knights |

|---|---|---|

| Military Role | Kataphraktoi heavy cavalry | Heavy cavalry, armored knights |

| Land Ownership | Pronoia grants; tax/toll rights, non-hereditary mostly | Hereditary land grants (fiefs) |

| Political System | Centralized imperial control | Decentralized feudal lords |

| Military Service | Expected from pronoiars under emperor’s authority | Owed by knights to their lord |

| Social Status | Aristocracy tied to imperial favor | Feudal nobility independent locally |

Overall, while Kataphraktoi and Pronoia holders fulfilled some roles similar to Latin knights, the Byzantine system lacked the landed aristocratic feudalism characterizing Western Europe. The emperor’s strong hold and the conditional nature of grants created a unique model of military aristocracy.

- Byzantines used heavily armored cavalry called Kataphraktoi rather than knights.

- Pronoia grants gave rights to collect taxes or tolls, not permanent land ownership.

- Imperial authority was centralized; land or privileges depended on the emperor.

- Military service was tied to these grants but under direct imperial control.

- The system differed fundamentally from Latin knightly feudalism with hereditary fiefs.

Did the Byzantine Empire Have Its Own Version of Native Knighthood? The Tale of Kataphraktoi and Pronoia Unveiled

Short answer: Yes, but the Byzantine “knighthood” differed profoundly from the Latin knights. While Western Europe fleshed out feudal knights embedded in a mosaic of land-owning nobility, the Byzantine Empire painted a different picture—an empire-shaped mosaic of central power, imperial favor, and specialized cavalry called Kataphraktoi.

If you imagine knights as armored heroes mounted on mighty steeds, the Byzantines had their very own versions, the famed Kataphraktoi. These heavy cavalry units donned extensive armor, essentially Byzantine heavy cavalry veterans who clanked into battle with decades, even centuries, of legacy. They fulfilled a similar military role to the medieval Latin knights, striking fear in enemy lines and dominating battlefields.

But calling Kataphraktoi “knights” in the Western sense misses the major differences. The Byzantine society did not have a rigid feudal structure comparable to Western Europe. Instead, the imperial court tightly centralized power, leaving noble competition more about curry favor with the emperor than conquering and holding lands independently.

The Military Angle: Kataphraktoi vs. Latin Knights

Imagine a Western knight: clad in shining armor, mounted on a warhorse, sworn to a lord, tied to feudal obligations. The Byzantine Kataphraktoi look similar on the surface — densely armored heavy cavalrymen. But Byzantine cavalry expertly combined Byzantine tactics and armor suited for their diverse military challenges across centuries.

Kataphraktoi units were arguably more versatile. Unlike Latin knights who sometimes fought dismounted but mainly preferred the shock tactics of cavalry charges, the Byzantines mastered combined arms tactics. Kataphraktoi often coordinated with infantry and archers and demonstrated adaptability on the battlefield, reflecting the sophisticated military tradition of Byzantium.

During the Komnenian restoration (1080–1180), the Byzantines even employed Latin knights themselves as mercenaries. This unique melding highlighted the empire’s pragmatism but underlined another difference — Latin knights remained outsiders who came into Byzantine service, rather than reflecting native aristocratic military tradition.

Power Structures and Politics: Centralized Byzantine Empire vs. Feudal West

Here’s where things get truly interesting. The idea of knighthood in the West was inseparable from feudalism: landholding nobles wielded local power, owed service to higher lords, and passed lands through hereditary lines. This formed the classic pyramid of power familiar to medieval Europe.

The Byzantine Empire broke this mold completely. Instead of a diffuse feudal structure, the emperor exercised centralized authority. Titles and honors came straight from the throne. Nobles competed not by seizing independent domains but by gaining imperial favor. This kept ambitious aristocrats more dependent on the emperor than on inherited rights. It’s like chess where the emperor is the king, and the nobles are pawns vying for influence.

Pronoia: Byzantium’s Unique Approach to Land and Service

So, what was Byzantium’s version of rewarding military loyalty if not feudal fiefs? Enter the Pronoia system—special grants awarded by the emperor.

At first glance, it looked similar to feudal grants but was fundamentally different. Instead of giving permanent ownership of land, the emperor granted rights to collect taxes or tolls from certain areas, kind of like financial concessions. These privileges were revocable at will and non-heritable initially, keeping ultimate control firmly in imperial hands.

To illustrate: a noble might receive a Pronoia giving rights over a bridge toll or a tax district. They benefited financially but did not own land outright. They owed military or financial service to the emperor, and the grant could be revoked or reassigned, maintaining a centralized grip on power.

Evolution Under the Komnenoi and Palaiologos Dynasties

The Pronoia system evolved over centuries. During the Komnenoi dynasty, emperors started to award land linked with military service and loyalty — a bit closer to Western feudalism. But these grants were still not hereditary; they reverted to imperial control after the holder’s death.

It was only under the Palaiologos dynasty that some Pronoia grants became inheritable. Yet even here, the grants were often rights or duties rather than full land ownership. Recipients remained obligated to provide military or financial support, tethering them to the emperor’s authority.

The Real Differences: Why Byzantine ‘Knights’ Don’t Fit Latin Molds

Let’s break down the essentials. Latin knights represented a social class with hereditary land rights and obligations shaped by feudal law. Byzantine Kataphraktoi and Pronoia holders were more administrative and military functionaries embedded in an imperial hierarchy, where land was not owned but controlled through grants that could vanish overnight.

This created a dynamic where the emperor maintained far more direct influence than any feudal lord in the West could dream of. Byzantine knights didn’t form an aristocratic caste competing independently of the emperor. In fact, the decentralized power structure in the West gave Latin knights a different role—both military and political—that Byzantines deliberately avoided.

Why Does This Matter?

Understanding these differences challenges the way we view medieval military elites. It reveals how culture, politics, and military needs shape social institutions.

Could Byzantine knights have taken over Western Europe? Probably not. Their system prized centralized control and flexible, revocable grants. Latin knights thrived in a world where decentralized power broadened aristocratic influence. It’s a classic example of how different political environments give rise to distinct social orders, even in the realm of armored horsemen.

In Summary

- Byzantine native ‘knighthood’ centered on Kataphraktoi heavy cavalry, functionally akin to Latin knights but embedded in a different tactical tradition.

- Socially and politically, Byzantium rejected feudal fragmentation, favoring a centralized imperial system where favors like Pronoia replaced feudal land ownership.

- Pronoia were imperial grants—revocable, initially non-heritable rights or duties, evolving into inheritable privileges only late in the empire’s life.

- Latin knights represented a hereditary feudal aristocracy unaffiliated with imperial centralization, creating dissimilar social roles and long-term stability in the West.

The Byzantine Empire did have a form of native knighthood, but it wore different armor—the armor of centralized power and imperial favor. No mere copy of the Latin knight, it was a distinctive symbol of Byzantium’s unique political and military world.

So, next time you picture a knight, remember: not all heavy cavalry wore Western-style spurs and played feudal chess. Some clanked to the emperor’s tune.

Did the Byzantine Empire have a native form of knighthood similar to Western knights?

Byzantium did not have native knighthood like in Latin Europe. Instead, they used the *Pronoia* system where the emperor granted rights or duties, often linked to taxation, not full land ownership or hereditary titles.

What was the role of Byzantine *Kataphraktoi* compared to Latin knights?

*Kataphraktoi* were heavily armored cavalry, similar to Western knights in combat function. They fought as elite cavalry but were part of a long-standing military tradition distinct from the feudal knights.

How did the Byzantine *Pronoia* system differ from European feudal land grants?

*Pronoia* grants were revocable rights tied to the emperor, not inheritable land initially. Recipients collected taxes or tolls and owed military or financial support, unlike the hereditary land ownership typical in feudal Europe.

Did the Byzantines use Latin knights in their military?

Yes, especially during the Komnenian period, the Byzantines employed Latin knights as mercenaries or regular soldiers. This was a practical addition to their forces rather than a native aristocratic structure.

Were Byzantine land grants eventually inherited like European knightly estates?

Only in the Palaiologos period did *Pronoia* grants become inheritable. Even then, these grants often represented rights rather than land. The system remained more centralized and tied to imperial authority than feudal.