Medieval mills operated using water power to drive millstones that ground grain into flour, with the miller overseeing the entire process and maintaining the equipment.

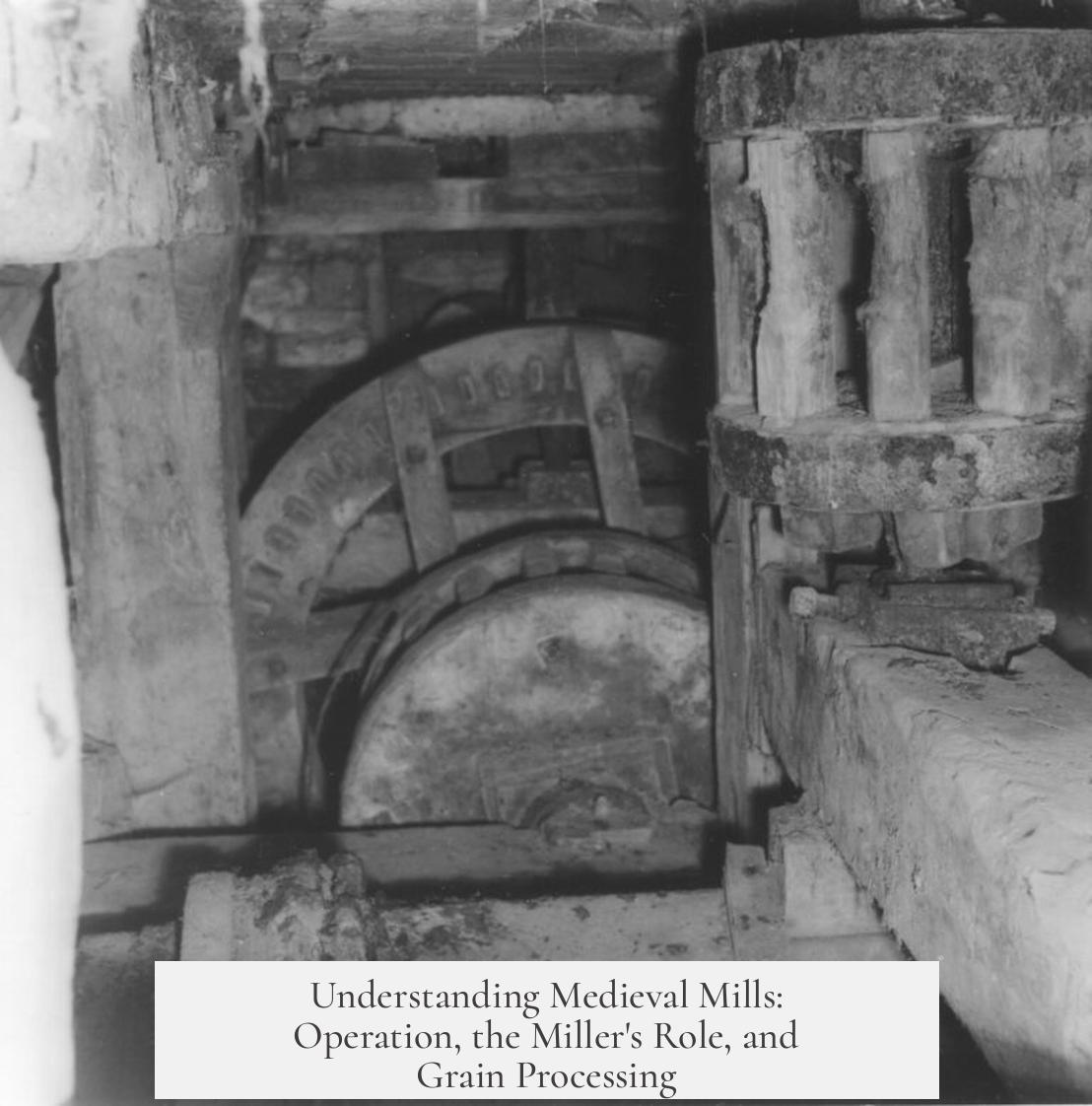

The core of a medieval mill was the water wheel, which converted flowing water into mechanical energy. The water wheel connected through a system of wooden gears to the upper millstone, known as the ‘runner’. This runner millstone rotated at approximately 120 revolutions per minute. The lower millstone, called the ‘bedstone’, remained fixed to the floor. Together, these stones crushed the grain into flour.

The miller played a crucial role in adjusting the millstones. He precisely set the distance between the runner and the bedstone to control the flour’s texture. This spacing could be altered during operation to produce various grades of flour, ranging from coarse meal to fine white flour.

Grain feeding was a controlled process. The miller opened the hopper situated above the stones to let gravity feed grain into a slanted trough called the ‘slipper’. Standing next to the slipper, the miller gently shook it to regulate grain flow. This ensured a steady, even feed into the central hole of the rotating runner stone.

Once ground, the flour exited through grooves in the runner stone, reaching the outer rim. From there, it traveled down a chute to the lower floor. The flour either went into bins for storage or passed through a mechanically powered sieve also driven by the water wheel. The sieve refined the flour into uniform grades. Refined flour dropped directly into sacks, while coarser, unrefined flour was bagged separately. A helper often assisted by guiding flour-filled chutes into sacks for efficient collection.

The water wheel’s power was versatile. By uncoupling the upper millstone from the drive shaft, the miller could reassign power for other tasks within the mill. This included operating a hoist to lift heavy sacks of grain to upper levels and running a mechanical sieve for flour refinement.

The miller’s duties extended beyond milling. Grain delivery was a key responsibility; sacks of grain arrived by cart or wagon. The miller attached a chain hoist to the drive shaft. Using this, he lifted the heavy sacks to the top floor, called the ‘sack floor’, and emptied them into grain bins.

The miller’s skill deeply influenced flour quality. He felt the flour and adjusted operating speed, grain feed, and millstone spacing to achieve the desired fineness. This craftsmanship was often referred to as having ‘the miller’s touch’. Experienced millers identified potential mechanical problems by subtle changes in sound during operation.

Maintenance constituted a large segment of the miller’s work. Flour dust built up and clogged machinery, requiring regular cleaning—daily in busy summer months and at least weekly otherwise. The water supply system demanded upkeep. The mill pond, dam, and raceway had to remain clear of debris and structurally sound to ensure steady water flow.

Mechanical components received constant attention. Wooden gears, shafts, and couplings wore quickly and needed repair or replacement. The mill wheel itself required periodic inspection and maintenance.

Millstones demanded special care. They needed ‘dressing’—reshaping and sharpening grooves to maintain grinding efficiency. This process could occur as often as every four weeks for continuously operated mills. Eventually, worn-out millstones had to be replaced, a costly investment for mill owners.

In addition to machinery care, millers maintained the mill building and often a bakery, especially in earlier medieval periods. It was common for millers to bake bread, using the flour from customers as well as their own share. Baking filled slower periods when grain supply was low.

Most millers did not work alone. The profession involved training apprentices or family members as helpers. Apprentices learned milling techniques, machinery upkeep, and sometimes baking skills. This tradition helped sustain milling knowledge across generations.

| Task | Description |

|---|---|

| Operating Water Wheel | Convert water flow into rotational energy to turn the runner stone at ~120 rpm |

| Adjusting Millstones | Set and fine-tune gap between stones for flour grade control |

| Feeding Grain | Control grain flow via hopper and slipper to feed runner stone evenly |

| Flour Handling | Guide flour into bins or sacks; use powered sieves for refinement |

| Maintenance | Clean machinery, maintain water infrastructure, dress and replace millstones, repair wooden gears |

| Raising Grain | Operate hoist to lift heavy sacks to top floor bins |

| Baking (Optional) | Use flour for bread making during non-busy times |

| Training | Teach apprentices or helpers milling and baking skills |

The miller’s job required both physical effort and technical knowledge. They balanced machinery operation, grain processing, equipment maintenance, and sometimes baking. Master millers had a refined sense of their equipment’s condition and could adjust settings to produce consistent flour quality. Their expertise was integral to medieval agriculture and food supply chains.

- Water wheels powered the runner millstone at ~120 rpm to grind grain.

- Millstones were adjustable to control flour quality and fed grain via a hopper and slipper.

- The miller managed grain input, machinery operation, flour collection, and equipment upkeep.

- Dressing millstones and maintaining wooden gears were vital to smooth milling.

- Millers often baked bread and trained apprentices in milling and baking skills.

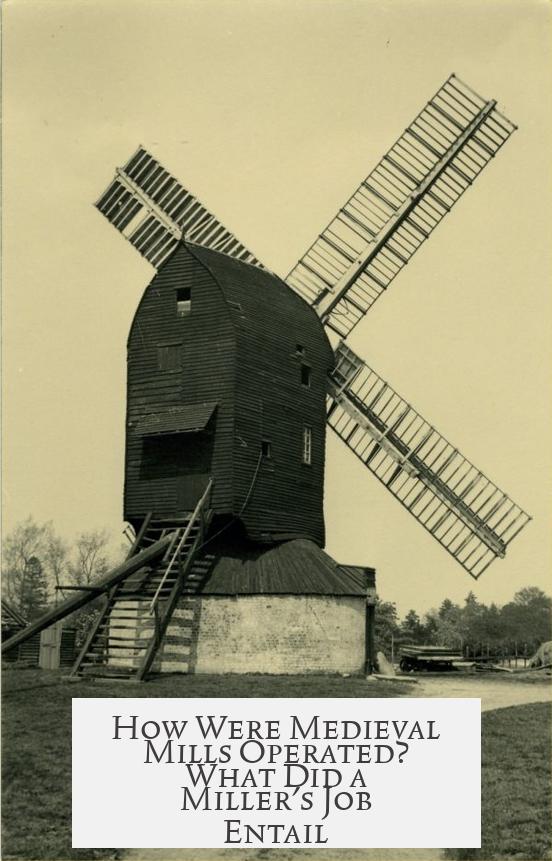

How Were Medieval Mills Operated? What Did a Miller’s Job Entail?

Medieval mills were marvels of their time—impressive feats combining nature, mechanics, and human skill. The operation of these mills revolved mostly around harnessing water power to turn massive stones that ground grain into flour. And the miller’s job? It was far beyond just pushing a button or flipping a switch. It required finesse, insight, and a lot of hard work.

Let’s peel back the wooden gears and dive into what made these mills tick, and what it took to be the person running the show.

Power From the Water Wheel: The Heart of the Mill

The primary force behind medieval mills was the water wheel. Picture a large wooden wheel spinning roughly 120 times a minute, driven by a steady flow of water diverted cleverly from a mill pond or stream. This wheel’s rotation connected to a system of gears, which transferred its energy directly to the upper millstone, known as the runner.

The bottom millstone, or the bedstone, stayed fixed to the floor, creating a grinding duo. The runner stone spun over the bedstone, and together they crushed the grain fed between them.

Precision in the Grind: Adjusting the Millstones

Operating a mill wasn’t about setting it and forgetting it. The miller constantly monitored and adjusted the gap between the runner stone and the bedstone. Why? Because different grades of flour demanded different textures. Fine white flour needed tighter spacing than coarse grist meant for livestock feed.

This spacing could be tweaked on the fly, often multiple times during operation. Too close, and the stones could jam or produce flour too fine; too far apart, and the grain wouldn’t grind properly. It was a delicate balance, requiring skill and an instinctive sense for the machinery’s “feel.”

Feeding the Beast: Grain Flow Control

The grain started its journey in sacks hauled, mostly by wagon, to the mill. At the top floor—the “sack floor”—the miller hoisted and tipped grains into bins using a chain hoist powered by the water wheel itself. The genius of gravity then took over.

From the bins, grain poured into a sloping wooden trough called the slipper. The miller stood at the slipper, shaking it gently to control the flow of grain feeding into a hole in the center of the runner stone. Too much grain at once could clog the stones; too little and the wheel wasted power.

The Tale of the Flour: From Grinding to Packaging

Once ground, the flour emerged from the runner stone’s grooves, traveling out to the rim, then down a chute to lower floors for sorting. At times, the flour went to bins before passing through a mechanical sieve—also powered by the water wheel. This sieving separated the flour into uniform grades.

For less precise milling, the flour might go directly into sacks without refinement. A helper usually managed the flour’s careful transfer from chute to sacks, ensuring no precious grain was wasted.

The Miller: More Than Just a Grinder

The miller wore many hats. Sure, he managed the flow of grain and the grind, but the craft went deeper. With seasoned hands and ears, a miller could sense when stones needed dressing—that is, reshaping and sharpening the grooves that actually ground the grain. This was often necessary every four weeks or so during busy times to keep productivity high.

Plus, mill machinery made entirely from wood wore out fast. Gears, shafts, and couplings demanded constant maintenance—and the mill’s wheel, dam, race, and pond required upkeep to prevent blockages or damage.

Keeping Water and Wood in Check

The water system was just as important as the stones. The miller cleared debris from the pond and race to keep the power flowing steady. Without a reliable water supply, the mill stopped—simple as that.

Wooden gears and shafts wore on the job and had to be repaired or replaced frequently. It wasn’t just manual labor but a mechanical balancing act to prevent costly downtime.

Baking: Sometimes the Miller’s Bonus Skill

In earlier medieval times, many millers also baked bread. It made sense—they had the flour and often ran the village oven too. During slower milling seasons, the miller (or family members) baked bread and other goods, making good use of the miller’s share of the grind.

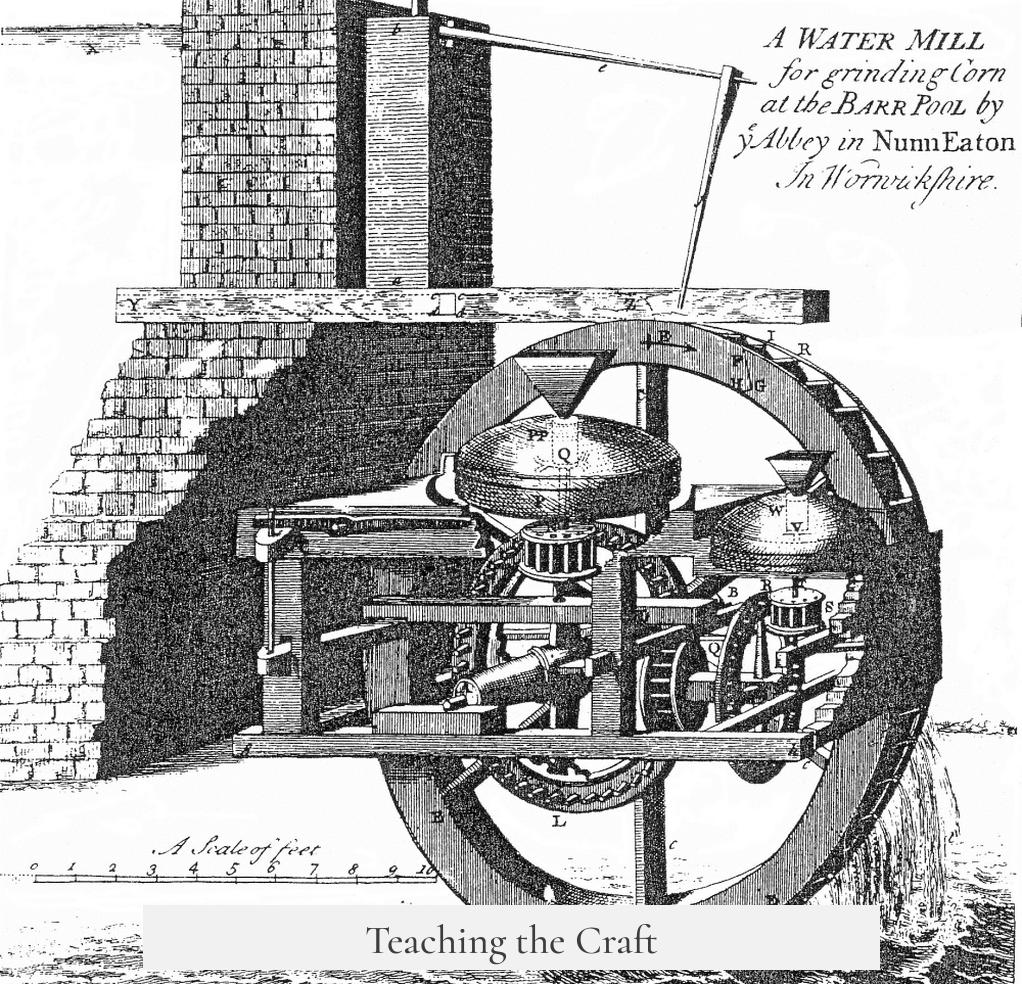

Teaching the Craft

Milling was a craft passed down by hands-on teaching. The master miller trained apprentices and family helpers to handle everything from grain handling to machine maintenance. This skill was known as “the miller’s touch,” a mix of instinct and experience.

Why Should You Care About Medieval Mills?

Understanding how medieval mills worked shows us how human ingenuity blended with nature long before electricity. It was a demanding, skilled trade requiring mechanical savvy, physical strength, and a deep connection to the natural rhythms of water and grain.

Next time you enjoy a slice of bread, remember the miller. His expertise transformed humble grain into the staple that sustained communities.

Quick Summary Table: Medieval Mill Operation Highlights

| Aspect | Detail |

|---|---|

| Power Source | Water wheel driving the runner stone at ~120 rpm |

| Millstones | Runner (top, spinning) & bedstone (bottom, fixed) |

| Grain Feed | Gravity-fed via hopper and slipper, controlled by miller |

| Flour Processing | Sieving for quality, bagging by helpers |

| Miller’s Skills | Stone dressing, machine maintenance, water system care |

| Additional Duties | Baking, training apprentices, building upkeep |

Curious about other medieval crafts? Stay tuned for more peeks into the past’s working world!