Rhodesia apologists can largely be characterized as gaslighting racists who seek to whitewash a regime built on systemic white supremacy and racial oppression. This is the consensus among scholars and analysts who have studied the period extensively. These apologists attempt to minimize or distort the reality of Rhodesia’s history, reframing the regime’s actions as a fight against communism rather than a defense of racial segregation and political disenfranchisement.

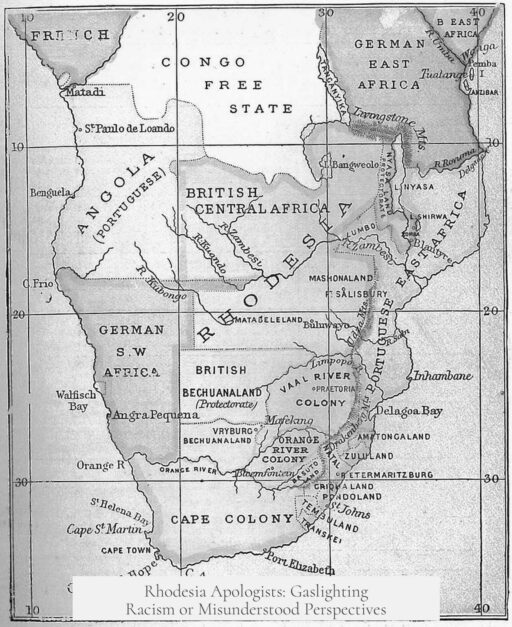

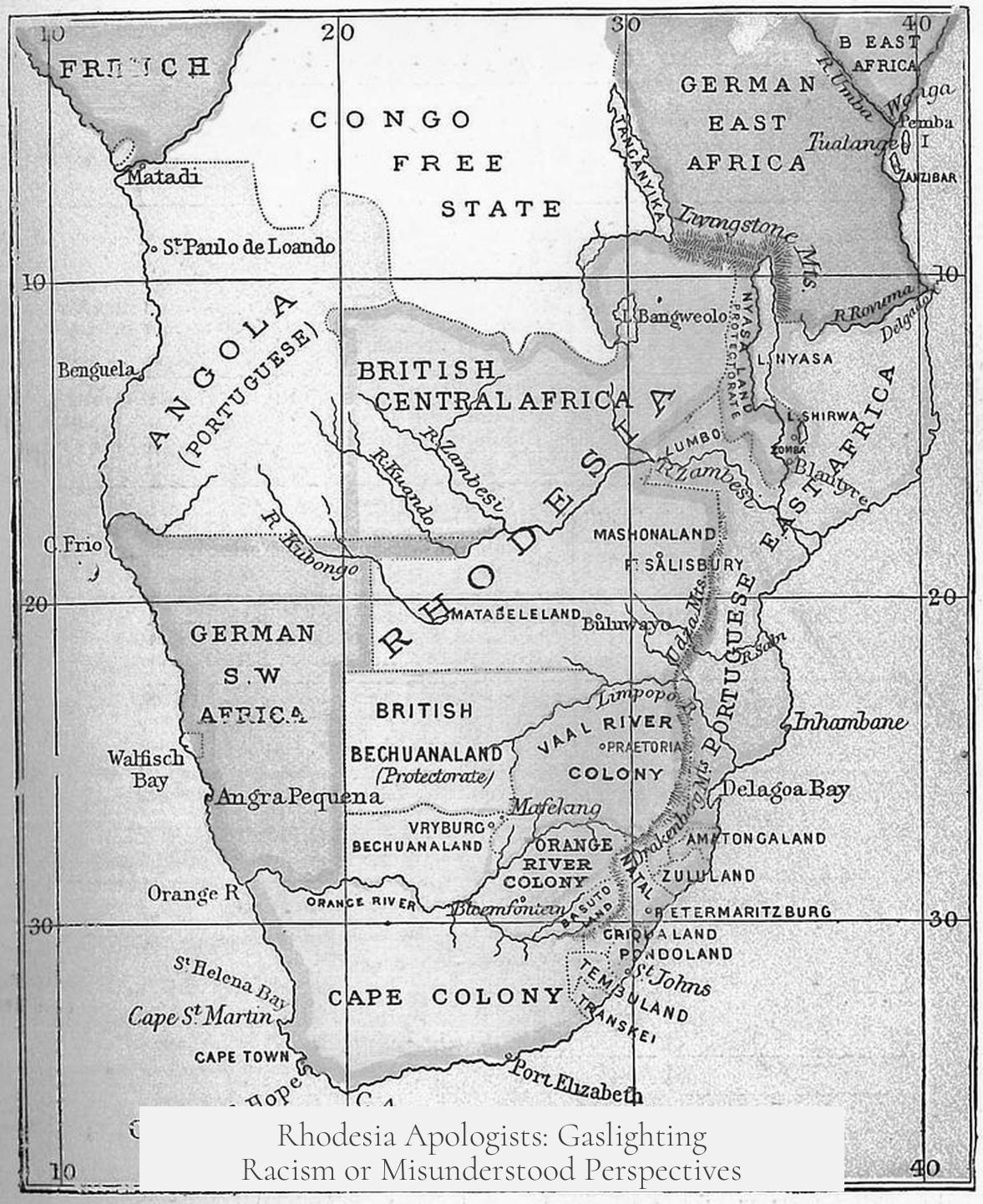

The foundation of Rhodesia (Southern Rhodesia until 1965 and Rhodesia until independence in 1980) lies in colonialism, built on racist ideologies like Cecil Rhodes’ “White-Man’s Burden.” The British South Africa Company’s sponsorship and the settlers’ worldview entrenched a sense of racial hierarchy. Indigenous Africans were infantilized and politically marginalized throughout this era.

Land and political control were strictly segregated through laws that favored white settlers. For example, the Land Apportionment Act of 1930 legally divided land along racial lines. Native reserves were deliberately poor quality lands, intended to limit African economic competition. The Native Land Husbandry Act of 1951 disrupted traditional communal African land ownership, forcing many Africans into labor for white enterprises. These policies supported a deeply racialized caste system.

Several discriminatory laws enforced racial segregation:

- Sale of Liquor to Natives and Indians Regulations (1898): Targeted non-white populations.

- Immorality and Indecency Suppression Act (1903): Criminalized relationships between black men and white women, reinforcing white supremacy.

- Public Services Act (1921): Barred indigenous people from civil service roles, maintaining white political dominance.

- Industrial Conciliation Act (1934): Excluded black workers from trade unions and reserved skilled jobs for whites.

African political enfranchisement was an illusion. Voting qualifications were deliberately set, with income and property thresholds unreachable for most Africans, effectively excluding them from meaningful participation. For instance, the 1923 Constitution required a £100 annual income or £150 in property, while most Africans earned about £3 monthly. These barriers tightened in later years.

Rhodesia apologists often frame the regime’s struggle as one against communism. This narrative ignores the legitimate aspirations and political activism of African nationalists. African political opposition began in the late 1940s and grew into organized parties fighting for civil rights and equal governance. The Ian Smith regime responded harshly, banning parties and imprisoning leaders.

The “fight against communism” argument collapses under scrutiny. Zimbabwe’s post-independence government never became communist. The claim is a convenient myth to deflect from the racist foundations of Rhodesia. It also dismisses the complex socioeconomic and political motives behind African nationalism in the region.

Rhodesia apologists’ narratives amount to historical denial and perpetuate white supremacist legacies. Their perspectives often ignore or diminish the systemic racial violence and legal discrimination burdening indigenous Africans. These apologists seek to rewrite history, obscuring the oppressive realities of the Rhodesian state.

For deeper understanding, works like Luise White’s Unpopular Sovereignty offer critical insight into Rhodesia’s enduring fascination and the motivations of its apologists. Further resources include expert debates found on specialized forums addressing Rhodesian history.

- Rhodesia apologists promote a sanitized, false narrative.

- The Rhodesian regime institutionalized racial segregation and disenfranchisement.

- Discriminatory laws controlled land, labor, and political rights to uphold white supremacy.

- Claims that Rhodesia’s struggle was against communism ignore indigenous African political activism.

- Historical evidence overwhelmingly shows Rhodesia apologists as gaslighting racists denying systemic oppression.

So, are Rhodesia apologists all just gaslighting racists, or is there something I’m missing?

Simply put: Rhodesia apologists are overwhelmingly gaslighting racists, and here’s why that matters. There’s no neat middle ground where their views can be rescued from the swamp of denial and distortion. This isn’t just about historical debate. It’s about recognizing when someone spins a tale that downplays a brutal regime, excusing systemic oppression and racial domination under the guise of some noble fight.

But before jumping to conclusions, let’s unpack this tangled web of history, laws, and narratives. Maybe somewhere in there, we find that “something” people ask about when they question if apologists are really just gaslighting racists or if there’s more nuance overlooked.

The Gaslighting and Racism of Rhodesia Apologists – What’s Going On?

Think of gaslighting as someone confidently telling you that what you clearly see—like a blatant act of racism—is actually “not that bad” or “misunderstood.” Rhodesia apologists do this routinely. They spin the brutal reality of the Ian Smith regime into a rosier picture. According to direct experience and expert observation, these apologists usually supported, or at least sympathized with, the white minority rule that put systemic racism at the core of Rhodesia’s policies.

They don’t just argue with facts—they actively diminish the lived racist realities, attempting to erase the deep wounds colonialism and segregation inflicted on the black majority. The truth? They are often outright white supremacists.

Even stating this bluntly might feel harsh, but it’s necessary. The apologists’ defense mechanisms boil down to: “It wasn’t about race, it was about stopping communism.” And oh boy, we’ll dive into why that argument misses the whole point.

From Colonial Roots to Racial Hierarchy

To understand Rhodesia, we start in 1890 with Cecil John Rhodes and his British South Africa Company. The colony was founded explicitly on a worldview called the “civilising mission.” It meant, in short, that white settlers believed they had the duty to bring “civilization” to what they considered “darker” parts of the world.

This wasn’t just talk. It was the blueprint for a system of racial hierarchy that infantilized and demeaned the indigenous Africans. Africans were regularly called “boys” and “girls,” regardless of their adult status. The word “houseboys” or “housegirls” for adult domestic servants captured this mental imprisonment perfectly.

Segregation wasn’t subtle or accidental—it was the cornerstone of society. Public amenities, toilets, park benches—everything split along color lines, enforcing everyday humiliation and exclusion.

Political Disenfranchisement: Moving the Goalposts

Technically, Africans could vote. The catch? The qualifications were set to be impossible for most black citizens to meet. Think: to vote, you needed an income of £100 a year or own property worth £150 as per the 1923 Constitution. When most Africans earned about £3 a month, this was a cruel joke.

Fast forward to 1951, these qualifications increased drastically. By 1959, even some white voters began to feel the squeeze, slowly revealing the racial motivations behind the high barriers for voting rights. Politics was a closed club where the black majority’s voice was stifled.

Legally Enforced Segregation – Because Equality Was Too Much

Take the Land Apportionment Act of 1930. It legally segregated land so Africans got the worst lands—poor quality, unsuitable for farming. “Native reserves” and “tribal trust lands” sound benign, but they forced Africans into poverty and dependency.

The Native Land Husbandry Act, 1951, further stripped communal ownership rights, imposed modern farming methods, and limited cattle ownership. Africans who couldn’t comply faced fines or jail, pushing them into low-wage labor on European farms or in mines.

Other laws get downright oppressive: the Immorality and Indecency Suppression Act criminalized relationships between native men and white women, breeding fear and hatred. The Public Services Act banned indigenous people from government jobs, while trade unions were closed off to black workers, preserving white monopoly over skilled labor.

The “Fight Against Communism” Fairy Tale

Rhodesia apologists love to paint the Smith regime’s struggle as a valiant battle against communism. It sounds plausible on the surface, especially during the Cold War years. But scratch deeper, and this excuse falls apart.

Firstly, this narrative ignores the real political movement emerging from 1948 onwards. African nationalism grew rapidly, initially through trade unions led by figures like Benjamin Burombo. This was not communism – it was political activism for civil rights, equality, and democratic participation.

The Ian Smith government outlawed African political parties and imprisoned leaders, not because of communism, but to silence legitimate political opposition by the black majority.

Secondly, post-independence Zimbabwe wasn’t communist. Far from it. The notion that Rhodesia fought a communist takeover is historically inaccurate. It instead fought against the rightful political empowerment of its indigenous people.

How Do Rhodesia Apologists Keep Up This Charade?

Much of the apologists’ worldview is recycled propaganda from the Rhodesia Herald—the mouthpiece of the Rhodesian Front. This paper ignored the aspirations of black Zimbabweans and spread fear about communist threats, cultivating ignorance.

When apologists recycle these tropes today, they embrace an intentionally distorted version of history. It’s a comfortable myth that hides their complicity in endorsing racial supremacy.

So, Is There Anything You’re Missing?

Is there a hidden nuance? Could Rhodesia apologists have any valid points? The short answer is no, but understanding why these myths persist helps us tackle the problem.

Rhodesia apologists are not just misinformed—they often willfully ignore overwhelming evidence because confronting this ugly past threatens their identity or political views. They engage in gaslighting by denying or minimizing racism and the brutal realities of segregation and disenfranchisement.

Yet, some appear “fascinated” by Rhodesia for complex reasons including nostalgia for colonial order, attraction to militant narratives, or frustration with modern multiracial states. For a deeper dive, Luise White’s Unpopular Sovereignty offers a well-researched look at why this morbid fascination lingers.

Additionally, online discussions and FAQs, including from scholars like u/profrhodes and u/swarthmoreburke, unpack how these apologists fit into wider patterns of denial and white supremacy.

Practical Tips to Spot and Challenge Rhodesia Apologist Arguments

- Watch for minimization: If someone claims Rhodesia wasn’t racist, ask for specific evidence countering the well-documented laws and segregation practices.

- Question the communist argument: Point out Zimbabwe’s post-independence history and the strong civil rights roots predating any Cold War influence.

- Demand recognition of African political activism: Highlight leaders and moments like Benjamin Burombo and early trade union movements.

- Expose infantilization language: Challenge the casual use of terms like “houseboys” showing racial condescension.

- Use primary sources: Refer to historical acts such as the Land Apportionment Act or the Native Land Husbandry Act to ground discussions in facts.

Conclusion: Clarity Over Comfort

At the end of the day, Rhodesia apologists frequently gaslight their audiences and cling to racist frameworks. They aren’t victims of misunderstanding; they are often propagators of a false narrative that risks whitewashing systemic injustice. This truth doesn’t just serve history—it is essential for learning, reconciliation, and preventing repetition of such discriminatory regimes.

So, no, you aren’t missing much if you conclude that Rhodesia apologists are gaslighting racists. The nuance lies not in their excuses, but in studying the resilient political activism and brutality endured by the black majority. That’s the reality Rhodesia apologists often want you to overlook.

“To understand history, one must not only remember who kept the truth but recognize who fought to bury it.”

Q1: Are Rhodesia apologists simply trying to deny racism was central to Rhodesia’s regime?

Yes. They often minimize the racial oppression under Ian Smith’s white minority rule. Many aim to obscure the significant racial injustices and the colonial mindset that shaped Rhodesia’s policies.

Q2: Was racial segregation legally enforced in Rhodesia?

Absolutely. Acts like the Land Apportionment Act (1930) and Native Land Husbandry Act (1951) legally segregated land and limited African rights. Various laws restricted political and economic participation for the black majority.

Q3: Do Rhodesia apologists have a valid argument that the regime fought mainly against communism?

No. That view ignores the core racial oppression. The ‘anti-communism’ claim is often a cover story used to justify the regime. It dismisses the legitimate African nationalist goals for independence and equality.

Q4: How did colonial beliefs influence Rhodesia’s racial policies?

The settlers held the belief in a “civilising mission” rooted in white supremacy. Africans were infantilized and treated as inferior. This worldview justified segregation and denial of rights in legal and social systems.

Q5: Were Africans allowed meaningful political participation under Rhodesian rule?

No. Voting rules set income and property thresholds so high that most Africans could not qualify. These requirements ensured white political dominance despite nominally open suffrage.