The Spanish did not conquer the Aztecs solely because of military superiority. Hernán Cortés’s conquest relied largely on exploiting internal divisions within the Aztec Empire, forming powerful native alliances, and the devastating impact of European diseases, alongside limited but impactful use of European weapons and strategic leadership.

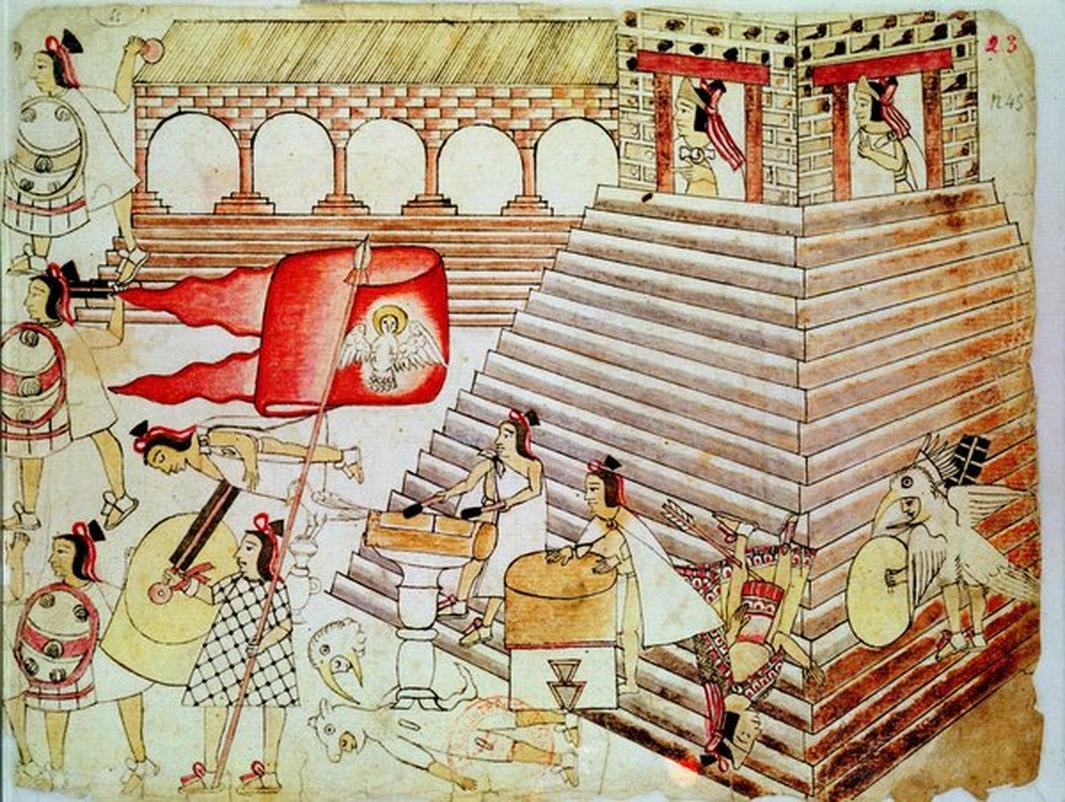

The Aztec Empire was not a fully centralized state but a fragile confederation known as the Triple Alliance. It ruled over many vassal city-states rather than directly governing all territories. This system meant that when the Aztec emperor showed weakness, subject cities often sought to break free. Cortés recognized this vulnerability immediately upon arrival. He skillfully played factions against each other by promising protection to Aztec vassals who opposed the central power while maintaining a façade of alliance to the Aztec emperor.

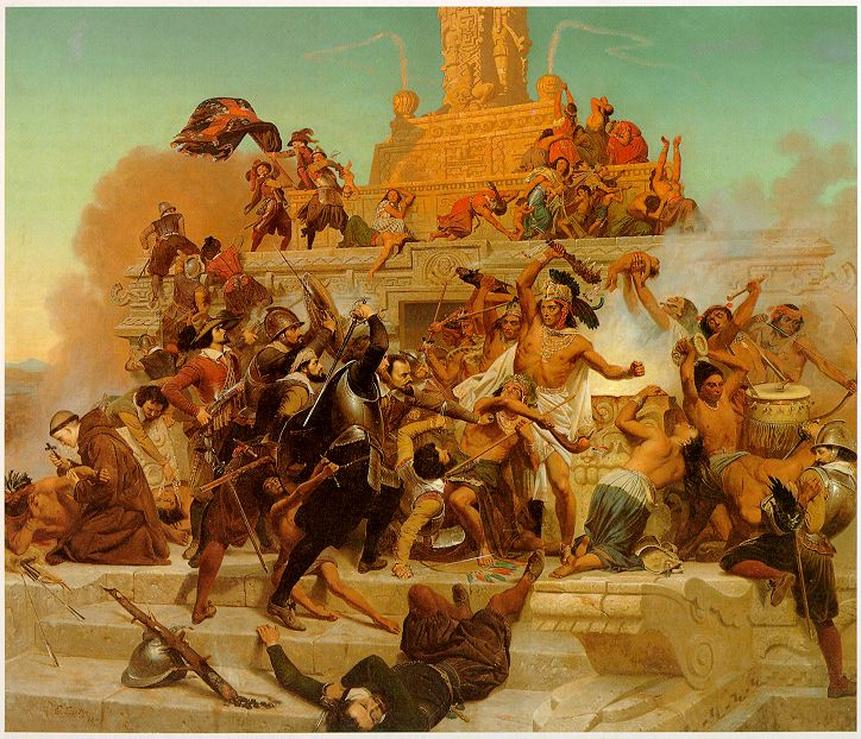

This diplomatic approach fractured Aztec cohesion. Many disgruntled provinces joined Cortés, swelling his forces dramatically. According to Cortés’s own estimates, by the final battle for Tenochtitlan, he commanded an army of over 100,000 soldiers. These forces were mainly indigenous groups hostile to Aztec rule, such as the Tlaxcalans. Without this vast native support, the Spanish numbers would have been insufficient to challenge the Aztecs’ numerical superiority.

European diseases, especially smallpox, devastated the Aztec population. At the time Cortés arrived, Tenochtitlan was suffering a large-scale smallpox epidemic that killed nearly half its inhabitants within several years. The native peoples had no immunity to these diseases, which severely weakened Aztec military strength and social organization. Disease played a fundamental role in reducing resistance and facilitating the Spanish conquest.

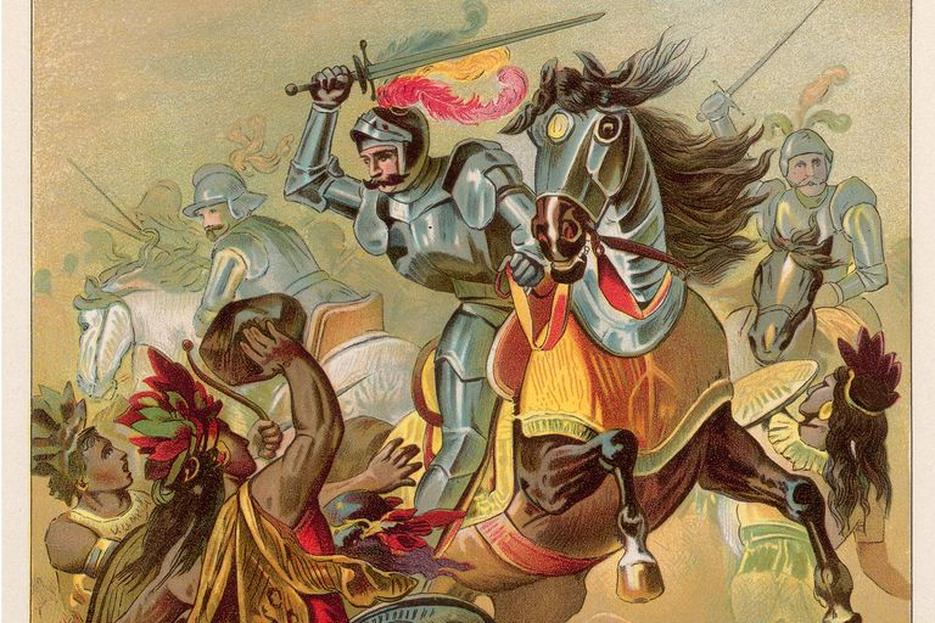

The Spanish military technology did give advantages but was not the decisive factor initially. Guns were slow to reload, had low accuracy, and limited range, making them less effective in early battles. Cortés primarily relied on disciplined troops wielding crossbows and iron weapons. Cavalry impressed the Aztecs greatly due to their unfamiliarity and psychological impact but did not guarantee battlefield dominance. The Spanish also used iron arrowheads, sometimes adopted from Indigenous allies, to improve their armaments.

Cortés established strong psychological dominance through strategic choices. One famous example is his deliberate scuttling of most of his ships to prevent any thoughts of retreat among his men. This tactic bolstered morale and commitment, ensuring his troops fought with determination since returning to Spain was no longer an option. These choices proved vital in maintaining a sustained campaign far from home.

The conquest took two attempts to capture Tenochtitlan, highlighting that the Spanish were not overwhelmingly superior militarily at first. The eventual victory owed much to the combination of fractured Aztec political structure, indigenous coalitions, disease, and psychological warfare. Spanish military technology complemented these factors but did not independently secure conquest.

| Factor | Role in Conquest |

|---|---|

| Aztec Political Division | Cortés exploited fractious vassals and internal dissent. |

| Native Alliances | Provided majority of the fighting force against Aztecs. |

| Disease (Smallpox) | Decimated Aztec population, disrupting military and society. |

| European Weapons | Used mostly for intimidation; guns less effective initially. |

| Cortés’s Strategy | Psychological tactics like sinking ships ensured army loyalty. |

- Cortés’s victory was multifaceted, not just military superiority.

- Internal Aztec weaknesses and native grievances were critical.

- European diseases drastically weakened Aztec resistance.

- Spanish technology contributed but was not decisive at first.

- Strategic leadership ensured effective use of forces and alliances.

Did the Spanish Conquer the Aztecs Because of Military Superiority? If Not, How Did Cortés Do It?

Contrary to popular belief, the Spanish conquest of the Aztecs was not won by sheer military superiority. Hernán Cortés’s victory was a masterclass in strategy, diplomacy, and circumstance rather than a simple outmatch on the battlefield.

Let’s unpack how Cortés achieved this spectacular feat, despite facing a sprawling and formidable empire like the Aztecs.

The Fragile Foundations of the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire wasn’t a solid monolith. It was more like a patchwork quilt stitched together from a confederation known as the Triple Alliance — three city-states with others paying tribute rather than being directly ruled. This gave the empire a delicate power balance.

Aztec emperors had to walk a tightrope. They needed to appear strong to keep rebellious vassals loyal. But the moment they showed weakness, these subjugated city-states would jump at the chance to break free. This internal division was a massive chink in their armor.

Enter Cortés. He quickly sensed this political instability and exploited it brilliantly. Instead of simply attacking, he wooed the vassal cities, offering them protection from the Aztecs themselves. Meanwhile, he maintained a facade of loyalty to Mexico’s emperor. This diplomatic chess game played a huge role in undermining Aztec unity.

Thousands of Native Allies: The Real Muscle Behind the Conquest

You might picture the Spanish conquest as a small band of Europeans toppling a giant empire with superior weapons. The truth? The Spanish were a tiny minority.

In reality, Cortés rallied tens of thousands of indigenous soldiers from provinces opposed to Aztec rule. His core Spanish force was heavily outnumbered — think 600 Spaniards versus an army that swelled to over 100,000 with native allies by the final confrontation.

The Tlaxcalans and many other groups had no love for the Aztecs. Cortés just needed to organize them. This coalition of native forces was decisive in tipping the scales against the Mexica.

Deadly Diseases: The Invisible Enemy

One of the unluckiest factors for the Aztecs was disease. Cortés and his men inadvertently brought smallpox and other European illnesses to which the native population had no immunity.

When the Spanish entered Tenochtitlan, a horrifying epidemic was already wiping out about half of the city’s inhabitants. This decimated not just civilians but also soldiers, disorganizing Aztec society and severely crippling their capacity to resist.

Disease was no minor side effect; it was a catastrophic blow that undermined both Aztec morale and military strength.

The Myth of Military Technology as the Deciding Factor

We often hear tales of Spanish guns and horses as unstoppable forces. But the truth is a bit less dramatic.

- Early firearms were slow to reload, inaccurate, and had limited range.

- Cortés relied more on crossbowmen than musketeers because of this.

- Cavalry scared the Aztecs, but only because they had never seen horses before. It wasn’t an absolute military advantage.

- Iron weapons and armor gave some edge, but were countered by the Aztecs’ skill and numbers.

In fact, the psychological impact of these weapons mattered more than their practical battlefield effectiveness during initial contact. Native numbers and alliances outweighed technology.

Cortés’ Bold Strategy: Burning Bridges

Cortés knew commitment was key. So, he destroyed most of his ships, leaving escape off the table for his men. This move forced loyalty and a do-or-die mindset.

With no way home, his men fought with fierce determination, pushing relentlessly forward. This psychological tactic helped sustain their grueling campaign in hostile lands far from Spain.

Putting It All Together: More Than Just Superior Arms

The Spanish conquest was a complex mosaic:

- Political savvy to exploit rifts in the Aztec political structure.

- Building and leading vast indigenous alliances eager to challenge Aztec dominance.

- The catastrophic effect of smallpox and other diseases.

- The psychological effect of military technology, rather than outright effectiveness.

- The unwavering commitment of Cortés’s forces, catalyzed by strategic risk-taking.

The Spaniards needed more than just swords and guns; they needed brains, cunning, and a little luck with timing.

Why Did It Take Two Attempts to Take Tenochtitlan?

Not to brag, but if it had been simple military superiority, Cortés would have conquered Tenochtitlan on his first try.

Yet, he had to retreat and reorganize before finally capturing the city a year later. This shows the Aztecs’ formidable resistance and that victory was far from a foregone conclusion.

It was a siege steeped in attrition, betrayal, alliances, and disease — none solely dependent on technological dominance.

Lessons From History: Beware the “One Factor” Explanation

This story reminds us: history is messy. The Spanish conquest cannot be boiled down to a tale of better guns or bolder fighting. It involves political strategy, native agency, environmental factors, and even deadly microbes.

Understanding this multi-faceted reality enriches our comprehension and prevents simplistic myths from wandering in.

If you’re hungry for a deeper dive, Matthew Restall’s Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest is an excellent resource that dismantles common misconceptions surrounding the event.

Summary

The Spanish conquest of the Aztecs wasn’t a Hollywood battle of superior warriors but a layered saga:

- Political exploitation: Cortés played divided factions against each other.

- Native alliances: Tens of thousands joined him against the Aztecs.

- Disease devastation: Smallpox ravaged the Aztec populace and troops.

- Psychological edge: Weapons and horses scared but didn’t guarantee victory.

- Strategic risk-taking: Sinking the ships ensured his men were all in.

So the next time someone says the Spanish triumphed just because they had better weapons, you can confidently reply, “Not quite. It was brains, alliances, and a touch of deadly luck.”