Ancient Romans practiced religion through a combination of public rituals, private worship, and adherence to a complex pantheon of gods closely linked to daily life, state affairs, and family traditions. Their religious system blended civic duties with spiritual needs, integrating ceremonies into politics, military campaigns, and domestic life.

In early Rome, religion and the state were inseparable. Priests managed major sacred observances and performed rituals in temples dedicated to gods like Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus. These temples had distinct clerical hierarchies responsible for formal sacrifices and land-wide festivals. Every election, law, or military campaign began with ceremonies, showing religion’s role in legitimizing state actions.

Personal and household religious practice also played a key role. Most Roman homes contained a Lararium, a small shrine where offerings were made to household gods called Lares. These entities protected the family and its property. The paterfamilias—the male head of the household—often acted as priest for minor rituals, such as prayers for good health or safe voyages. Families could also make visits to temples to commission official sacrifices if needed.

The Romans believed in a vast collection of gods governing every aspect of life. Gods had specific domains: Janus ruled doorways and transitions, Mars was associated with war, and so forth. To maintain divine favor, people offered prayers and sacrifices tailored to each god’s domain. For example, a stuck door might require a burnt cake offering to Janus. Traveling necessitated sacrifices to the god of roads. This specialization made religious observance detailed and frequent.

Public sacrifice was a central ritual, often involving animal offerings such as bulls or chickens. These rituals were highly symbolic. A notable example from Roman culture depicts a sacrifice to Cybele, the Magna Mater, involving drenching a participant in bull’s blood to promote protection on a military campaign. Sacrifices often demanded strict protocols and were conducted by trained priests.

Romans also engaged in personal prayer and small-scale offerings. Soldiers in difficult situations might make humble promises to gods, such as future sacrifices of livestock. Common citizens prayed quietly to household deities or favored gods like Janus when facing challenges such as illness, business ventures, or travel. These individual acts complemented official ceremonies.

Roman religion was inclusive and adaptive, especially as the empire expanded. While Rome had a familiar pantheon derived from Italic and Etruscan origins, conquered peoples retained their traditional religions. They were encouraged—sometimes compelled—to honor Roman gods like Jupiter alongside their native deities. This syncretism helped maintain harmony across diverse cultures.

During the civil war and imperial era, new religious cults gained popularity. In Roman terms, a “cult” referred to organized worship of a specific god, not inherently fraudulent. Cults such as those devoted to Mithras, Isis, and Christianity attracted followers with distinctive beliefs and practices. Mithraism appealed to soldiers and slaves, Isis attracted wealthy aristocratic women and intellectuals, while Christianity, considered atheistic by Romans because it denied all gods but one, grew among slaves, women, and poor citizens. These cults often required private devotion, but their members still participated in state rituals.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Public Religion | Temple priests conducted sacrifices and ceremonies integrated with politics and military events |

| Private Worship | Household shrines (Lararia) honored Lares; paterfamilias led domestic sacrifices |

| Religious Diversity | Adopted foreign gods; local traditions persisted in provinces; state holidays honored Roman gods |

| Religious Cults | Devotion to specific deities like Mithras or Isis; Christianity emerged among marginalized groups |

| Functions of Gods | Each god controlled specific life aspects, rituals matched these specializations for favor |

Roman religion filled practical and spiritual needs. It was a constant part of life, with rituals marking transitions, businesses, and health. Ancient Romans felt the gods actively influenced everyday events.

- Trained priests ran public temples and state rituals tied to governance and military.

- Private worship focused on household gods, with the paterfamilias overseeing family rites.

- Romans worshiped a broad pantheon with specialized gods for different life areas.

- Foreign gods and cults integrated into Roman religion, especially in the empire’s vast territories.

- Popular cults devoted to gods like Mithras, Isis, and Christianity offered alternative religious identities.

How Did Ancient Romans Practice Religion?

Ancient Romans practiced religion as a deeply woven part of everyday life, blending public ceremonies with private devotion. Their approach was practical, inclusive, and deeply ritualistic, where gods influenced every aspect of existence—from elections to household chores. This fascinating system reflects a society where belief, politics, and daily routine intertwined with sacred duties.

If you’ve ever wondered how they managed all those gods and rituals without going mad, let’s unpack the colorful world of Roman religion. Spoiler: It’s a mix of official pomp, private prayers, and a bit of divine multitasking.

Religion and Governance: One and the Same

In early Rome, religion wasn’t compartmentalized like today. The line between church and state was practically invisible. Every major public event, like elections, laws, or military campaigns, kicked off with a sacrifice or ceremony. Imagine launching a new war strategy without a prayer to Jupiter or Mars—it just didn’t happen.

These rituals weren’t winged by amateurs. Trained priests, specialists of their crafts, led religious observances. The city boasted temples dedicated to various gods, each with its own clerical hierarchy. The priests made sure that sacrifices and ceremonies ran without a hitch. Roman citizens expected no less than divine approval for their public affairs.

The Private Touch: Household Gods and Daily Prayers

But Romans weren’t just about grand temple rituals. Most households had a small shrine—called a Lararium—dedicated to the Lares, the household gods. These divine protectors were almost like family members who watched over the home and its fortunes.

The paterfamilias, the oldest male (think father or grandfather), served as the family priest for minor sacrifices. Something simple: a sick child or a new business venture? A quick offering at home did the trick. Yet if you wanted the full religious experience, you could visit a temple and hire an official priest for a formal sacrifice. Roman religion was flexible like that.

Even immigrants could bring their gods, enriching the Roman pantheon with foreign deities. This inclusivity helped Rome absorb different cultures smoothly through religion. Plus, most Romans shared a common set of gods, picking whichever suited their need at the moment—essentially, divine problem-solving on demand.

Everyday Life Was Full of Ritual

Roman religion wasn’t just a Sunday affair; it was a constant companion. A well-known example comes from popular culture portrayal where Atia, the mother of Augustus, sits beneath a bull during a bloody sacrifice to Cybele, the Magna Mater, hoping to ensure her son’s safety on a military journey.

Think this sounds extreme? Well, personal prayers and small offerings were just as common. Take the soldier Vorenus quietly praying to a clay bust of Janus—a god of doorways and beginnings—when starting a business. Or Pullo, another soldier, desperately crushing cockroaches to make a tiny sacrifice while imprisoned, promising a white chicken when he got free. These intimate moments reveal how Romans sought divine favor anytime, anywhere.

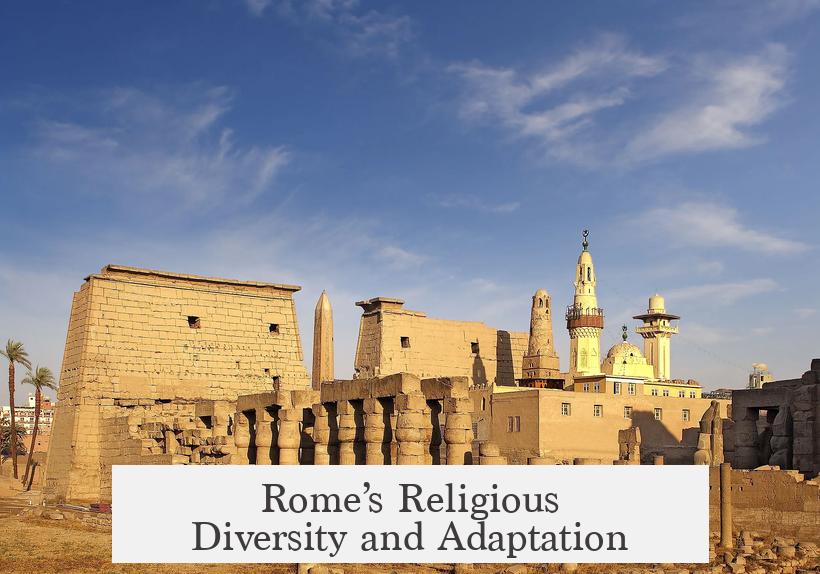

Rome’s Religious Diversity and Adaptation

Rome’s religious life wasn’t static. Within the city, people worshipped familiar gods drawn from Italic and Etruscan traditions. However, as the empire expanded, local religions persisted across far-flung territories like Egypt, Gaul, and Judea.

These regions often retained their traditional rituals, yet Roman authority required they build temples to Jupiter, signaling allegiance to Rome’s supreme god. Curious how Rome managed this religious patchwork? It embraced a pragmatic pluralism that balanced respect for local traditions while asserting imperial unity.

The Rise of Cults in the Turmoil of Empire

During the civil wars and Empire era, new religious cults became hugely popular. Unlike today’s association of ‘cults’ with fringe or frauds, the Romans saw cults as organized religions dedicated to a single god.

Take Mithraism, a cult merging heroic and savior elements popular among slaves and soldiers, or the cult of Isis, an Egyptian goddess who attracted rich women and intellectuals. Christianity also emerged then, quickly spreading among the oppressed and marginalized, offering hope of paradise amid suffering.

Interestingly, Romans saw Christians as atheists, because they denied all gods but one. Yet Christians still had to attend state rituals honoring traditional gods, highlighting the complex religious dynamics of Roman life.

Specialized Gods and Ritual Offerings: Everything Has a Deity

The Roman pantheon was vast. Seriously, there was a god for just about everything. This created an entire priesthood dedicated to remembering their names and domains—a full-time job! If your door wouldn’t stop sticking, it meant you’d upset Janus, god of doorways, and you’d better bake a small cake to burn as a peace offering.

Planning a journey required prayer to the god of roads. Having a child needed the favor of fertility gods. With such specialized deities, you’d never run out of reasons for a ritual or sacrifice.

The Lararium altar in each household kept the family connected to their gods. The Lares weren’t distant deities; they were close-by guardians who protected families but could also demand offerings if neglected.

Why Does This Matter? The Roman Religion Legacy

Roman religion teaches us how spirituality can deeply shape a civilization’s identity, politics, and daily life. It shows a culture where belief systems were not just private faith but public instruments of power and community.

This approach, combining structure with inclusivity and practical devotion, helped Rome hold together its vast empire for centuries. The flexibility to absorb new gods and integrate diverse practices kept the empire cohesive—even as new religions like Christianity rose to prominence, paving the way for a religious shift in Europe.

Wrapping It Up with a Roman Blessing

In sum, Romans practiced religion as an essential part of both public and private life. With trained priests, household shrines, sacrifices, and personal prayers, their spiritual world was vibrant and multifaceted. It surely kept life interesting—and perhaps helped explain why, after a long day, they always made time to appease Janus and keep those tricky doors working!

Feeling inspired? Maybe keep a little Lararium at home—for luck, or just a daily reminder that even the Romans knew a bit of prayer and ritual never hurts.