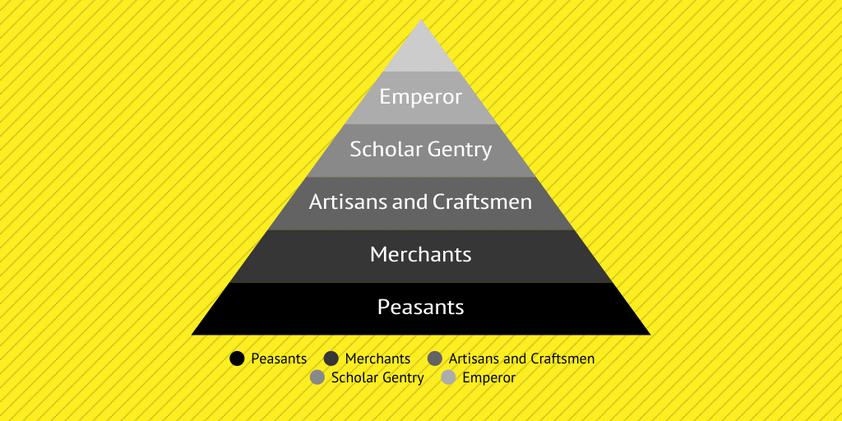

Ming Dynasty emperors appear more brutal than their Song counterparts largely due to the Ming founder’s decision to centralize all power and abolish the chief minister role that the Song dynasty relied on for governance. This shift in political structure created immense pressure on the emperor and fostered a more authoritarian style of rule, contrasting with the Song’s delegation system that had notable weaknesses.

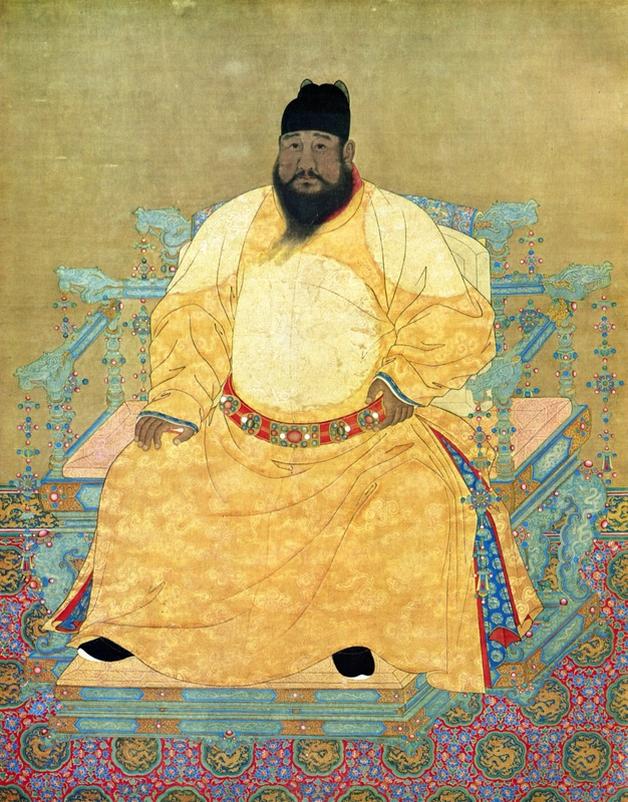

During the early Ming dynasty, Hongwu Huangdi initially appointed a chief minister who managed the civilian bureaucracy similarly to the Song model. However, he soon grew deeply suspicious that this minister plotted against him. After executing the chief minister, Hongwu issued his Ancestral Injunctions forbidding the appointment of any chief minister in the future. This decree meant Ming emperors had to personally oversee all state affairs and decisions, becoming the sole authority without intermediaries.

This move was driven by negative Song experiences. Historians criticized Song emperors for allowing chief ministers too much power, which at times led to disastrous outcomes. For example, Qin Hui, a powerful Song minister, orchestrated the wrongful execution of the patriotic general Yue Fei, damaging public trust. Additionally, Jia Sidao failed to defend the Song effectively against Mongol invasion, finally precipitating the dynasty’s fall. Emperor Huizong’s neglect of governance in favor of arts allowed ineffective ministers to weaken the state. These events seeded deep distrust toward delegation and ministerial authority.

To avoid these pitfalls, Hongwu’s policy required future emperors to exercise direct control over government processes. However, this imposed a significant burden on rulers who, unlike their scholars or bureaucrats, were often isolated and lacked administrative expertise. Some Ming emperors ruled rigidly and harshly, exercising their absolute power with severity to maintain control and avoid perceived threats.

Over time, this authoritarian model showed drawbacks. The Wanli Emperor, a later Ming ruler, famously rebelled against his demanding role. He refused to attend court meetings or endorse official documents, crippling government functions. Key offices remained vacant, and policy decisions became inconsistent and ineffective between 1600 and his death in 1620. This governance vacuum emboldened external enemies.

Naturally, the weakening Ming state invited military challenges. Nurhachi, founder of the Manchu state, perceived the Ming as a “paper tiger” due to their internal decay. He formally declared war in 1617 and defeated Ming forces decisively in 1619. His son Dorgon later seized Beijing, ending Ming rule and establishing the Qing dynasty. The legacy of rigid centralization without capable administrative structures contributed significantly to this decline.

- Ming brutality reflects the concentration of power in the emperor’s hands after abolishing the chief minister role, unlike the Song system of delegated governance.

- The Song experience, especially treacheries by chief ministers like Qin Hui and Jia Sidao’s failures, created mistrust toward delegation that influenced Ming policies.

- Absolute rule demanded by Hongwu proved burdensome, prompting severe rule by some emperors and neglect by others, undermining stability.

- The government’s collapse under the Wanli Emperor’s disengagement led to military defeats by emerging Manchu forces and the fall of the Ming dynasty.

The Ming dynasty’s brutal reputation stems from its founder’s reaction to prior failures of ministerial power in the Song period. Centralizing authority avoided delegation risks but sacrificed administrative flexibility and efficiency. These structural choices made Ming emperors more autocratic and, at times, harsher, with their rulers personally responsible for all government affairs. This system contributed to both internal instability and vulnerability to external threats, differentiating Ming governance and imperial behavior distinctly from the Song era.

Why Were Ming Dynasty Emperors So Brutal Compared to Their Song Counterparts?

The Ming dynasty emperors’ brutality largely stems from their decision to centralize power sharply, abolishing the chief minister role that was prominent during the Song dynasty. This step, driven by paranoia and a bitter distrust of trusted ministers, set the stage for a reign style that was both autocratic and often ruthless.

Let’s dive into the intricate political dynamics and psychological pressures that made Ming emperors harsher rulers than those in the Song era.

The Vanishing Chief Minister: A Recipe for Brutality

When the Ming dynasty was founded, its first emperor, Hongwu Huangdi, initially had a chief minister managing the day-to-day administration. This setup mirrored the Song dynasty’s approach, where powerful ministers handled much of the government business. But halfway through his reign, Hongwu’s trust evaporated. He believed his chief minister plotted to assassinate him—a chilling distrust that led to the execution of the minister and a groundbreaking decree: no chief minister would ever again be appointed.

Imagine the shockwaves this caused! Suggesting to reinstate the post meant death. The emperor became the undisputed decision-maker, the sole center of power. This move ensured no delegated authority could siphon off or challenge imperial control, but it also turned the emperor into a one-man government. Talk about piling on the responsibility!

Why Did Hongwu Fear Chief Ministers so Much?

- The Song dynasty offered a cautionary tale, infamous for its powerful ministers who often ‘ran the show’ with catastrophic results.

- The most notorious was Qin Hui, chief minister to the Song dynasty, who orchestrated the execution of General Yue Fei, a hero and symbol of loyalty. Historians still call this the darkest stain on Chinese imperial ministerial history.

- Later, Chief Minister Jia Sidao’s failure to defend the Song kingdom from Mongol conquest sealed the dynasty’s doom.

- Song Emperor Huizong, fond of art and poetry, delegated governance to incompetent ministers, which ended poorly with internal strife and the capital’s downfall.

Simply put, Hongwu’s harsh distrust wasn’t just paranoia—it was rooted in real disasters from the past. Avoiding delegation meant avoiding their failures.

The Double-Edged Sword of Absolute Power

This move, while securing short-term control, turned out to be a double-edged sword. The immense burden placed on Ming emperors was unprecedented. Raised amid luxury, suddenly these rulers were expected to personally manage every critical decision of a vast empire.

Not everyone thrived. Some emperors clung to Hongwu’s vision and ruled actively, often adopting strict, brutal measures to maintain order and authority. Others couldn’t handle the load. The Wanli Emperor is a prime example. By the late 1500s, he despised his government officials and refused to attend meetings or approve documents. Administrative chaos spread as positions remained vacant and decisions stalled.

The Wanli Emperor’s Abdication and Its Fallout

The reign of the Wanli Emperor brought turmoil. His disengagement didn’t just result in inefficiency; it weakened the dynasty’s very foundations. Around this time, Nurhachi—a rising Manchu leader—realized the Ming had lost their grip. In 1617, he declared war, and two years later, his forces defeated a Ming army in a humiliating defeat.

Nurhachi’s son, Dorgon, capitalized on this disarray. He marched the Manchu army into Beijing 25 years later, effectively toppled the Ming dynasty, and started Qing rule.

Comparing Ming Brutality with the Song Era’s Ministerial Rule

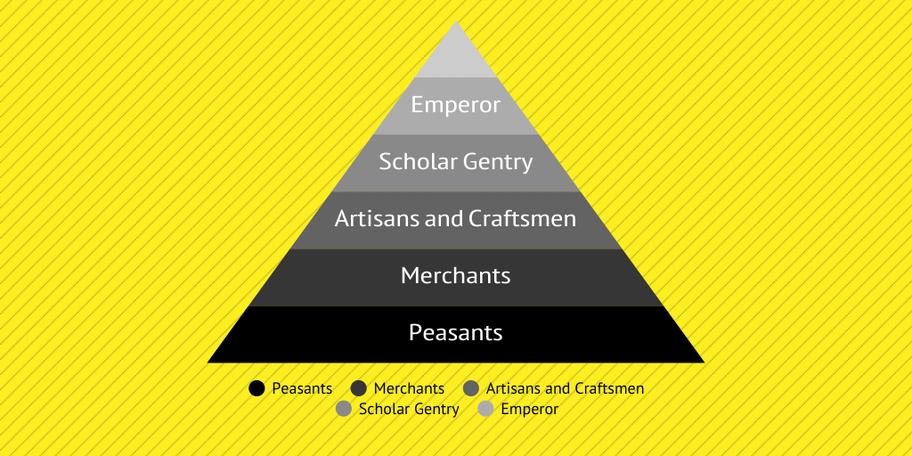

The Song emperors were less brutal but arguably less directly responsible for government actions due to the strong influence of their ministers. This delegation sometimes backfired horribly but also meant the emperor’s personal brutality was not the centerpiece of governance.

In contrast, the Ming emperors embodied autocracy itself. Their rule was personal, sometimes paranoid, and often severe, because every decision—good or bad—rested on them.

Lessons and Reflections: Why Does This Matter?

History shows that absolute power without checks can lead to harsh, sometimes brutal leadership. The Ming dynasty’s story warns against concentrating authority too tightly in one person’s hands, especially when coupled with distrust and fear.

This focus reveals how political structures influence leadership style. Would Hongwu have ruled so harshly if he trusted his ministers? Was brutality the price of trying to prevent betrayal and failure?

Understanding this context helps explain why Ming emperors are remembered as more brutal compared to their more laissez-faire Song predecessors, whose ministers often shaped the era’s political failings and successes.

In Closing

The Ming dynasty emperors’ brutality arises from a deeply entrenched fear of betrayal and incompetence. By abolishing the chief minister role, Hongwu Huangdi pushed all imperial responsibilities onto himself and successors. Some embraced this with harsh discipline, while others crumbled under the pressure, creating chaos that ultimately invited their dynasty’s downfall.

In contrast, Song emperors delegated power, sometimes disastrously, but avoided the personal burden—and the personal brutality—that came with sole rule. The Ming approach sacrificed administrative stability for concentrated control, showing how a political system molds a leader’s temperament and history’s judgment.

So next time you wonder “Why were Ming Dynasty Emperors so brutal compared to their Song counterparts?” remember it boils down to fear, power, and the price of absolute rule.

Why did the Hongwu Emperor abolish the post of Chief Minister?

He believed the chief minister was a threat after suspecting an assassination plot. To prevent power abuse seen in the Song dynasty, he banned the position permanently. This made the emperor the sole decision-maker.

How did the Song dynasty’s chief ministers influence the Ming’s distrust of delegation?

Song chief ministers often controlled the government, sometimes with disastrous results. For example, Qin Hui executed General Yue Fei, and Jia Sidao failed to stop the Mongol invasion. These failures led Ming rulers to centralize power tightly.

What impact did centralizing power have on Ming emperors’ rule?

It put heavy pressure on the emperor, who had to manage all decisions alone. Some rulers became harsh to maintain control, while others neglected duties, causing disorder and weakening the state.

Why did the Ming dynasty decline under later emperors like Wanli?

The Wanli Emperor avoided ruling directly, refusing to approve documents or hold meetings. This led to a chaotic government, empty offices, and weakened defense against external threats like the Manchu invasions.

How did Ming emperors’ brutality compare to failure in Song ministerial rule?

Ming brutality was a reaction to perceived Song failures where ministers gained too much power. The strict rule was meant to avoid those mistakes but also created its own problems of harsh rule and instability.