Alexander the Great is not directly mentioned in the canonical Protestant Bible but appears in extracanonical books and may be symbolically alluded to in prophetic texts. His presence in Jewish and Christian scripture varies by tradition and depends on historical timing, canon formation, and interpretative practices.

The Protestant Bible excludes certain books considered apocryphal, such as 1 Maccabees, where Alexander is mentioned. 1 Maccabees is part of the Catholic and Orthodox biblical canons but is classified as intertestamental, composed after Alexander’s death. Its historical focus on Jewish struggles following Alexander’s empire explains why direct references appear there rather than in older canonical texts.

Most biblical books were written before or around Alexander’s era (fourth century BCE). Texts like Chronicles, Psalms, Job, and Ecclesiastes were authored or compiled during times focused on the history and restoration of Israel. These books reflect a narrow scope centered on local history and religious identity, not the broader geopolitical developments influenced by Alexander’s conquests.

Indirect references to Alexander appear in symbolic prophecy, notably in the Book of Daniel and Sirach. For example, Daniel’s visions use animals and statues to represent successive empires. The “belly of brass” in Daniel 2 likely symbolizes the Greek empire under Alexander. Daniel 7 describes a leopard with four wings and heads, and Daniel 8 depicts a powerful goat defeating a ram, often interpreted as Greece overpowering Persia, directly aligning with Alexander’s historical conquests.

Sirach 10:10 includes a saying attributed by some scholars to Alexander’s sudden death: “A long illness baffles the physician; the king of today will die tomorrow.” The device of referencing a fallen powerful king may reflect on Alexander, known for his abrupt demise. However, these are indirect allusions rather than explicit mentions.

| Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

| Direct Mentions | None in Protestant Bible; appears in 1 Maccabees (Catholic/Orthodox canon) |

| Indirect Symbolic References | Book of Daniel’s beasts and statue; Sirach 10:10; Ezekiel and Zechariah prophecies possibly fulfilled by Alexander |

| Historical Timing | Most texts predate or are contemporary with Alexander’s reign; focus on Israelite history and restoration |

| Textual Fluidity | Canon formation varied; diverse Jewish traditions and loss of some texts complicate Alexander’s biblical presence |

Several hypotheses address why Alexander is not explicitly named. The Tanakh’s scope primarily covers pre-exilic events and post-exilic restoration, possibly excluding figures outside immediate Jewish concerns. Some scholars suggest priestly or scribal editors shaped the canon to omit certain historical details, though no direct evidence supports this.

The diversity of Judaism during the Second Temple period adds complexity. Religious writings varied widely, with no single authoritative set of texts. Some writings mentioning Alexander or related events may have been lost or never incorporated into the canon. Additionally, biblical authors often used coded or symbolic language to reference contemporary events or rulers indirectly, making explicit identification challenging.

Interpretations of Daniel’s visions remain speculative. The text is highly symbolic and has generated multiple readings across centuries. While many scholars associate the Greek empire and Alexander’s four-part division with Daniel’s imagery, these connections depend on theological and historical perspectives rather than explicit textual claims.

Alexander’s absence from extensive Jewish literature of the period raises further questions. Despite his prominent role in shaping the ancient world and influencing Judea’s political landscape, few Jewish texts outside 1 Maccabees highlight his exploits. This may reflect complex cultural, theological, or political reasons, as well as the particular interests of authors and communities preserving scripture.

- Alexander the Great appears directly only in extracanonical books like 1 Maccabees included in Catholic and Orthodox Bibles.

- Protestant Bibles exclude these texts, explaining the lack of direct mention.

- Symbolic references likely represent Alexander in Daniel’s prophetic visions.

- Most biblical texts focus on Israelite history, excluding wider geopolitical figures like Alexander.

- Textual fluidity and diversity of Judaism during Second Temple period complicate canonical representation.

- Interpretations of biblical symbols pointing to Alexander remain scholarly hypotheses, not certainties.

Why is There No Mention of Alexander the Great in the Bible?

Alexander the Great is not explicitly mentioned in the canonical Protestant Bible. Wait—hold that thought! That’s a jaw-dropping fact for many, given the legendary status of Alexander in history. So, why is this mighty conqueror, who carved an empire from Greece to India, missing from such a monumental religious compilation? Let’s delve into this fascinating mystery and break down the reasons.

First, it helps to understand a bit about the Bible’s makeup and the times during which its various books were written. The Bible, especially what we call the Tanakh or Old Testament, reflects specific historical moments and religious priorities rather than being a comprehensive world history book.

Different Bibles, Different Texts: Canonical Confusion Plays a Role

The notion that Alexander is absent from “the Bible” depends heavily on which version of the Bible we’re talking about. The Protestant Bible—the one many English speakers know best—does not include the book of 1 Maccabees. Yet this very text, present in the Catholic and Orthodox Bibles, does mention Alexander the Great, albeit briefly.

1 Maccabees, written after Alexander’s death, is an intertestamental book, bridging the Old and New Testaments. It’s here that his story appears, reflecting Jewish interaction with the historical aftermath of his conquests.

So Alexander’s story slipped through the cracks of Protestant canon formation. Protestant reformers redefined the canon by excluding texts they deemed less inspired. This editorial pruning explains why many Protestants never find Alexander in their Bibles. It’s a little like cutting a chapter out of your history textbook; you won’t learn that part without that chapter.

Timing Is Everything: When Were the Biblical Books Written?

Next, consider when the biblical texts were written relative to Alexander’s reign from 336 to 323 BCE. Many biblical books—such as Chronicles, Psalms, Job, Ecclesiastes, Ezra, and Nehemiah—stem from a period focused on the Jewish people’s history, identity, and temple restoration after the Babylonian exile.

These texts are centered on Jewish life and theological reflection rather than serving as a chronicle of global empires. Their content is insulated, not panoramic.

The Bible generally doesn’t elaborate on contemporary Gentile rulers unless they intertwined deeply with Jewish history. Alexander’s presence didn’t directly impact the Jewish narrative in the way Cyrus the Great or Nebuchadnezzar did. Hence, his footprint is minimal.

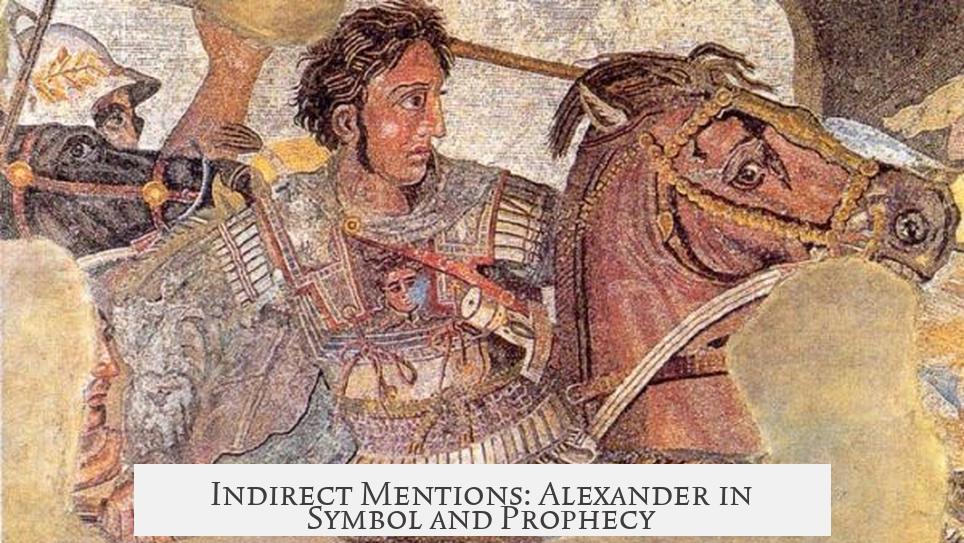

Indirect Mentions: Alexander in Symbol and Prophecy?

Despite no direct mention, scholars have identified possible indirect references to Alexander the Great—that is, if you love puzzles and cryptic symbolism.

Daniel’s prophecies are the prime canvas for these interpretations:

- Daniel 2:31-35 describes a frightening statue: gold head, silver chest, iron belly, and feet mixed of iron and clay. Some interpret the iron belly as symbolizing Alexander’s empire, crushed as his domain splintered after his death.

- Daniel 7:6 portrays a leopard with four wings and heads—an image linked to Alexander’s speed and the division of his kingdom.

- Daniel 8:2-8 details a conflict between a ram (representing Media-Persia) and a goat (Greece), with the prominent horn on the goat often identified as Alexander.

- Daniel 11:2-4 recounts a mighty Grecian king whose kingdom splits into four parts, reflecting the division after Alexander’s death.

Meanwhile, in Sirach 10:10, a cryptic line—“A long illness baffles the physician; the king of today will die tomorrow”—is believed by some, like Bradley Gregory, to allude to Alexander’s sudden, fatal illness, symbolizing a reversal of arrogance.

Still, these references are indirect and symbolic, not explicit naming. The Bible often cloaks political and historical realities in cryptic visions, especially apocalyptic literature, so scholars dance on the edge of interpretation.

Why No Direct Mentions? Theories and Speculations

So, why the silence? Several plausible explanations float around the academic halls:

- Scope of the Tanakh: The Hebrew Bible’s canon reflects pre-exilic history and the restoration period, focusing on religious identity, temple rebuilding, and the people’s relationship with God. Alexander’s era sits somewhat outside this focal point. The priestly and prophetic writers might have elected to exclude contemporary rulers like him.

- Fluid Textual Traditions: During the Second Temple period, what counted as “holy scripture” wasn’t fixed. Brennan W. Breed highlights manuscript fluidity at the time—textual debates roiled, and traditions varied. So, tales of Alexander might have circulated but didn’t crystallize into authoritative scripture.

- Lost or Coded References: Jewish literature was robust and multi-faceted, but many texts haven’t survived. Alternatively, references to Alexander might be cloaked metaphorically, like Rome concealed in apocalyptic visions. This veil of ambiguity challenges recognition.

- Diverse Judaisms: Old Judaism was never monolithic. Different groups had varying canons and concerns. What one sect might have celebrated as divinely inspired, another might discard.

- Subjective Interpretation: Prophetic visions in Daniel and elsewhere are enigmatic and open-ended. Without a Rosetta Stone, precise identification is a scholar’s guess rather than gospel truth.

So, What Does This Mean for Modern Readers?

The absence of Alexander the Great’s explicit name in the Bible teaches us something unexpected: sacred texts have specific missions. They guide faith and identity more than they detail earthly conquests. Alexander’s sweeping influence is undeniable in history, but the biblical story doesn’t always align with worldly timelines.

For those curious, exploring extracanonical books like 1 Maccabees enriches understanding, revealing Jewish perspectives on Alexander shortly after his death. These texts offer a unique window into how ancient Jews wrestled with the political realities left in his wake.

Could there be more lost writings chronicling Alexander’s role? Possibly. Considering how many ancient documents vanish into only fragments or references, it’s a humbling reminder that history is often partial and reconstructed.

Wrapping Up: What’s the Takeaway?

- Alexander’s story is missing from the Protestant Bible due to canon formation choices and textual priorities focused on Israel and restoration.

- He appears in 1 Maccabees, situated in Catholic and Orthodox Bibles, addressing the intertestamental period’s historical frame.

- Symbolic references, especially in Daniel, hint at Alexander’s empire through cryptic imagery of beasts and horns.

- Textual tradition fluidity, diversity of Jewish communities, and possible lost or coded references add layers of complexity.

- Interpretations remain speculative, inviting continuing scholarly dialogue and debate.

So next time someone quips, “Why no Alexander in the Bible?” you’ve got the script ready: it’s not a conspiracy, nor oversight—it’s a tale of timing, focus, textual traditions, and a hint of mystery. Do you think the Bible should have named him outright? Or does the subtlety suit the text’s sacred intentions better?

Why does the Protestant Bible not mention Alexander the Great directly?

Protestant Bibles exclude 1 Maccabees, where Alexander is mentioned. This book is part of Catholic and Orthodox canons but considered intertestamental by Protestants. The removal reflects differences in what texts are viewed as inspired.

Are there indirect references to Alexander the Great in the Bible?

Many scholars see symbolic references in Daniel’s visions, such as the leopard with four heads and wings. Sirach 10:10 may also allude to Alexander’s sudden death, but none explicitly name him.

Why might biblical texts around Alexander’s time avoid mentioning him directly?

Writings then focused on Israel’s history and restoration. The canon may have been shaped to exclude certain figures like Alexander. His influence might have been too broad or outside the scope of Jewish religious concerns.

Could some references to Alexander have been lost or coded in biblical texts?

Judaism was diverse with multiple traditions in the Second Temple period. Some texts that mentioned Alexander might be lost or contain indirect allusions, similar to how later empires are hinted at symbolically in apocalyptic literature.

How do scholars interpret the prophetic books in light of Alexander’s empire?

Prophecies in Daniel describe an empire breaking into four parts, matching Alexander’s successors. However, these images use symbolism, so interpretations vary and are not universally agreed upon within biblical scholarship.