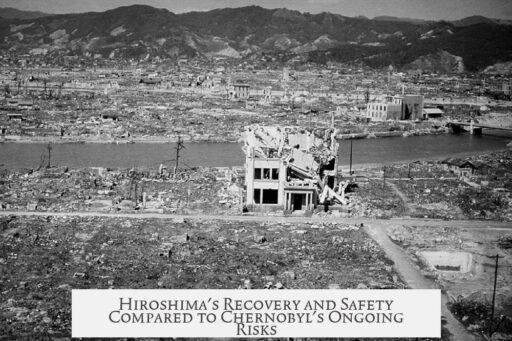

Hiroshima is safe to live in today because the atomic bomb released a relatively small amount of radioactive material high into the atmosphere, which dispersed widely and diluted quickly. In contrast, Chernobyl remains unsafe due to the massive release of radioactive fuel at low altitude, contaminating the local environment with persistent radioactive particles.

The Hiroshima bomb exploded as an airburst, releasing approximately 1 kilogram of fission products. It detonated 600 meters above the ground, sending radioactive particles into the upper atmosphere. These particles dispersed broadly, reducing local fallout. Any fallout that returned soon after was mostly vaporized or washed away by rain, drastically lowering contamination within weeks.

Conversely, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster released about 100 times more radioactive material. The destruction of reactor number 4 released vast quantities of long-lived isotopes stored in nuclear fuel. These particles were vented near ground level at relatively low temperatures, which caused heavy local contamination in the exclusion zone around the plant.

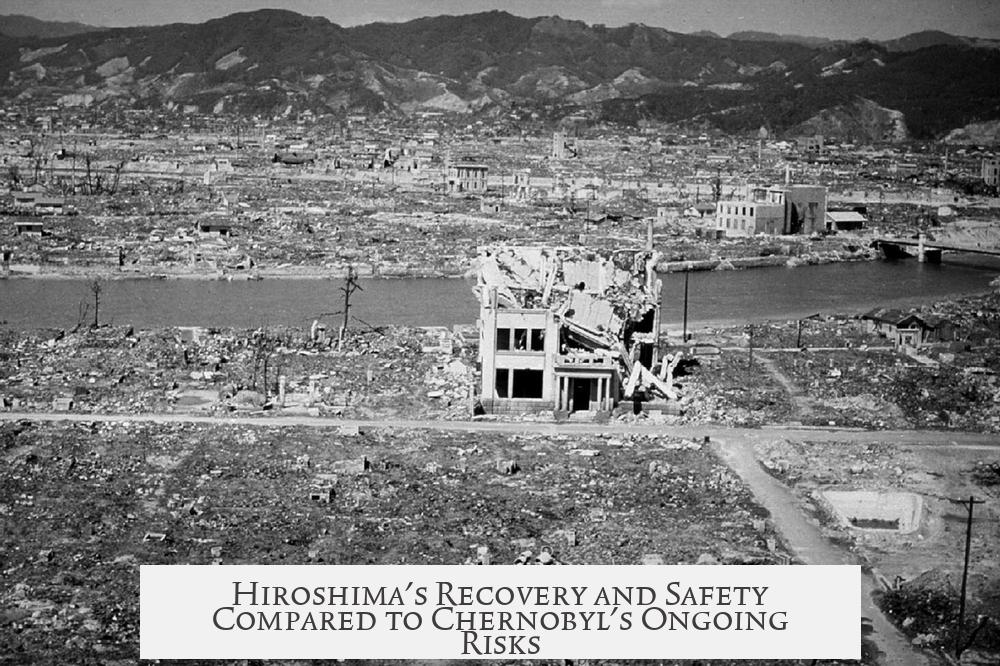

| Aspect | Hiroshima | Chernobyl |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Released | 15 kilotons (63 TJ) | ~10.5 GW-years (1.2 million TJ) |

| Radioactive Material | ~1 kg fission products | ~100X Hiroshima’s fission products |

| Fallout Dispersion | High altitude, widely dispersed, short-lived | Low altitude, local contamination, persistent hot particles |

| Contamination Type | Vaporized, washed away | Chunks, dust, ash, not diluted by time |

At Hiroshima, the airburst caused the radioactive fallout to rise rapidly and spread into the stratosphere. This process led to dilution across the globe, reducing local radiation levels to natural background within months. The intense heat vaporized much of the material, and rainfall further cleaned the area.

In contrast, Chernobyl’s reactor explosion and sustained fire spread radioactive particles in the immediate area. These particles include dust, ash, and debris contaminated with radionuclides. These materials settle on soil and structures and do not dissipate significantly over time. Contaminated chunks (“hot bits”) still pose health risks, especially if inhaled or ingested.

The Chernobyl exclusion zone remains hazardous because chronic exposure to residual radiation increases cancer risks and birth defects, even though radiation levels have dropped roughly 100 times since the accident. It is safe to visit the area briefly or work there with precautions, but continuous residency leads to steady radiation intake.

In Hiroshima’s case, the city was rebuilt without much understanding of radiation hazards in 1945. Population returned quickly. Over decades, radiation effects diminished, allowing safe, stable habitation. Today’s awareness of radiation risks would likely prevent such rapid rebuilding without remediation.

Chernobyl’s accident happened amid heightened knowledge of radiation dangers in the 1980s USSR. Authorities evacuated thousands immediately. Long-term cleanup and containment efforts continue because the scale of contamination and radioactive half-lives span decades or centuries.

- Hiroshima’s airburst released minimal local fallout; Chernobyl released massive fallout locally.

- Radioactive particles in Hiroshima dispersed globally; Chernobyl’s debris remains concentrated.

- Hiroshima radiation decreased quickly due to vaporization and weather; Chernobyl’s particles persist in soil and environment.

- Hiroshima was rebuilt rapidly post-war with little understanding of radiation; Chernobyl’s zone remains restricted due to chronic risks.

- Visiting Chernobyl is safe short-term, but living there risks long-term radiation exposure and health effects.

Why is Hiroshima a Safe Place to Live While Chernobyl Still Isn’t?

Let’s clear the air right away: Hiroshima is safe to live in today because the radioactive fallout was minimal and dispersed high into the atmosphere, while Chernobyl remains dangerous due to massive local contamination from a reactor meltdown that released vast amounts of radioactive material close to the ground.

Sounds like a simple explanation, but the story behind these two sites is complex and fascinating. Both are famous nuclear disasters, yet their aftermath couldn’t be more different. So why is one a vibrant city while the other is a ghost town? Let’s dive in.

Big Bang vs. Long Burn: Nature and Amount of Radioactive Material

In 1945, the Hiroshima bomb released an intense but brief burst of radioactive fission products—about a kilogram of them. These fission products were blasted high up into the atmosphere at blistering temperatures and swiftly dispersed. Picture fireworks that shoot so high, the smoke spreads thinly around the world before settling down. There was almost no local radioactive fallout to linger.

Fast forward to 1986’s Chernobyl nuclear disaster. Unlike a bomb, a nuclear reactor holds a massive, loaded fuel core. Reactor No. 4 was nearing the end of its fuel life, so it contained roughly 100 times more radioactive isotopes than the Hiroshima bomb. When it exploded, the release was at lower altitude and temperatures. This caused large amounts of radioactive ash, dust, and chunks of nuclear material to settle locally and heavily contaminate the surrounding land.

Scale Matters: Energy Released and Its Fallout Legacy

Hiroshima’s bomb excised around 15 kilotons of explosive energy—equivalent to 63 terajoules. That’s a powerful blast but limited in total radioactive material.

Chernobyl’s reactor No. 4, however, had generated a staggering 10.5 gigawatt-years of energy from fission before the accident, translating to about 1.2 million terajoules. This means the reactor contained at least 10,000 times the dangerous radioactive isotopes compared to Hiroshima’s bomb. It’s like comparing a bonfire to a blazing forest fire in size and potential harm.

How Fallout Travels: The Dynamics of Dispersion

The Hiroshima bomb exploded in the air, vaporizing most of its radioactive material and sending it high into the stratosphere. This high-altitude release allowed the fallout to diffuse broadly and dilute over time. Any radioactive particles that did fall soon got washed away by rain or dissipated, significantly reducing lasting contamination.

In contrast, the Chernobyl reactor exploded and then burned for days, spewing radioactive debris directly into the surrounding environment at lower altitudes. This included heavy particles like ash and chunks that settled nearby. They don’t just float away or dissolve with rain — these ‘hot bits’ persist, posing serious health risks if accidentally inhaled or ingested.

Health Risks: Short Term vs. Chronic Exposure

It’s important to know that radiation levels at Chernobyl dropped dramatically—by about 100 times—within the first 48 hours. This allows people to visit or work under strict safety protocols without immediate risks. However, living there means prolonged exposure, increasing risks of cancer and birth defects over years and decades.

For a single individual, this risk increase might seem small. But across whole populations, even a minor rise can result in many extra cancer cases. Some groups, like children, remain especially vulnerable.

Historical and Social Context: Changing Views on Radiation Hazards

Timing matters. Hiroshima’s catastrophe struck at the end of World War II, before the full dangers of radiation exposure were widely understood. Japan’s post-war rebuilding was rapid, driven by resilience, limited knowledge of radioactive hazards, and necessity. They rebuilt Hiroshima without modern-day remediation tech or extensive testing; it was a trial by fire, literally and figuratively.

Chernobyl, in contrast, happened in the 1980s when the world had a much clearer understanding of radiation’s long-term effects. The Soviet Union prioritized evacuations and established a large exclusion zone to minimize chronic exposure. This approach reflects a more cautious era focused on preventing further harm.

So Why Can You Live in Hiroshima but Not Chernobyl?

- Quantity of radioactive material: Hiroshima’s fallout was a tiny fraction of what Chernobyl released.

- Altitude and temperature at release: Hiroshima’s debris rose high and spread thin, while Chernobyl’s landed close and concentrated.

- Form of fallout: Hiroshima’s vaporized particles diluted quickly; Chernobyl’s heavy ash and chunks stuck around.

- Long-term exposure risk: Hiroshima’s site posed negligible radiation risk after years, but Chernobyl’s soils and structures remain radioactive.

- Era of disaster: Japan rebuilt quickly before full radioactive risk knowledge; the Soviet Union took precautionary exclusion steps due to greater understanding.

Lessons and Reflections

Does this mean nuclear bombs are less dangerous long-term than reactor accidents? Not quite. Each event has unique dynamics. Bombs unleash intense but brief energy with limited local contamination. Reactors, holding vast fuel and prone to prolonged fires, can cause extended contamination.

And what about future nuclear incidents? Modern nuclear disaster responses borrow lessons from both Hiroshima’s rebuilding and Chernobyl’s containment. Today, we’d expect extensive testing, remediation, and monitored resettlement to make affected areas safe again—likely a far cry from the past rush to rebuild or the long-term abandonments.

In closing, if you ever visit Hiroshima, enjoy its peaceful streets and vibrant culture. It’s a remarkable tale of resilience. But if you wander near Chernobyl’s exclusion zone (safely and guided), remember that nature still holds onto the radioactive scars. The difference comes down to how much nuclear “stuff” got loose, how it traveled, and how society responded.

Curious—would you rather live in a place rebuilt after a blast or in an abandoned zone frozen in radioactive time? Both are reminders of humanity’s power and fragility facing the atom.