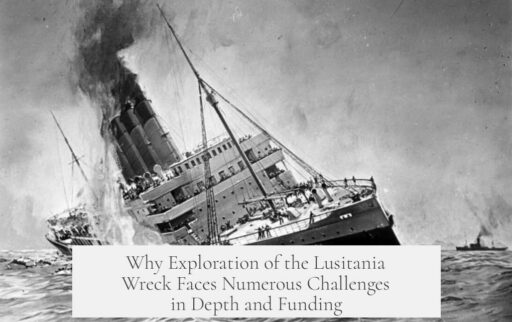

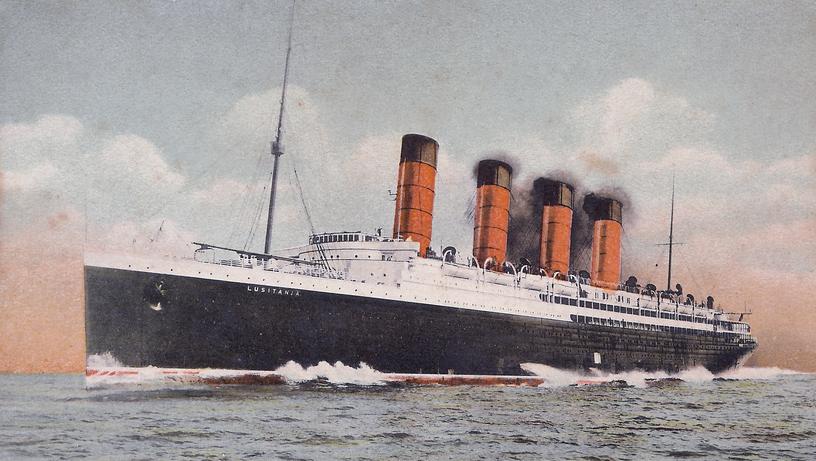

The Lusitania wreck remains relatively unexplored due to a mix of technical, financial, environmental, and historical factors that complicate access and investigation. Its depth, orientation, and location make dives difficult and expensive. Early interest focused more on salvage and treasure than thorough archaeological study, while modern methods are limited by costs and logistical challenges.

Shortly after the Lusitania sank in 1915, there was immediate interest in visiting the wreck. Much of this early attention stemmed from reports of valuable cargo aboard, including gold, bonds, and jewellery, as well as metals like brass and copper. These hopes for profit motivated rather than historical curiosity.

In 1935, a Glasgow-based group used an early echosounder to locate the wreck at about 95 meters depth. Diver Jim Jarratt made a brief dive but was hindered by poor lighting and the restrictive diving suits of that era. Bad weather cut the expedition short, and World War II halted further efforts for years.

Exploration efforts face significant technical challenges largely due to the wreck’s depth and environment. Sitting at roughly 90 meters, the Lusitania lies in an awkward zone for diving. The depth is too great for routine scuba diving but too shallow to justify deploying expensive deep-diving submarines or manned submersibles.

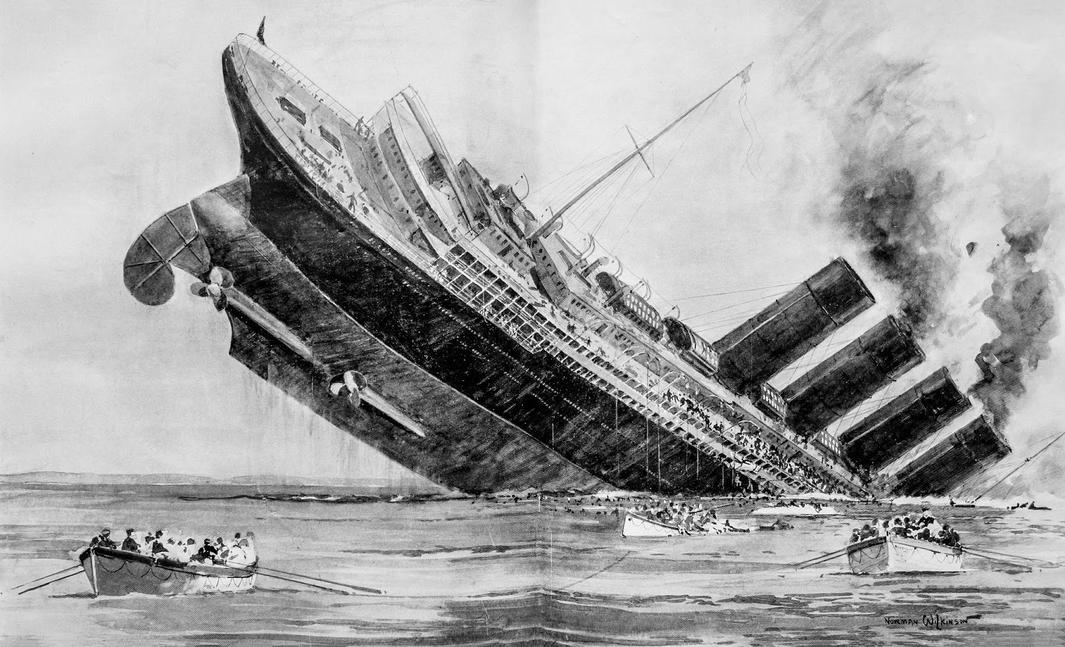

Moreover, the ship rests on its starboard side—the side hit by a torpedo—which obstructs a clear view of the damage area. This position complicates assessments of the sinking cause and structural conditions.

- Historical expeditions in the 1960s used scuba gear with compressed air, exposing divers to risks like nitrogen narcosis and hypothermia due to cold water temperatures.

- Attempts by salvage companies were constrained by limited budgets. For example, in 1966-67, salvage rights were bought for £1000, but funding the necessary support vessels exhausted available resources, preventing further dives.

In terms of technology, early expeditions involved limited reconnaissance with underwater photography. In 1982, Oceaneering International conducted a survey using Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs), capturing photographic and video evidence. Divers recovered salvageable items, but comprehensive archaeological work was minimal.

Marine archaeologist Bob Ballard advanced knowledge in 1993, deploying the submarine Delta with three ROVs to create a more complete photographic record of the wreck. Since then, trimix diving—a method permitting safer breathing at depth—has allowed several scuba visits, yet these remain constrained by depth and environmental hazards.

Financial constraints remain a consistent limiting factor. Procuring specialized equipment, sustaining support crews, and ensuring diver safety are costly. Many expeditions have short durations due to budgetary limits, restricting overall exploration scope.

Specifically, the greatest barriers are:

- Depth and Diving Complexity: 90 meters is beyond safe limits for many divers without advanced technology.

- Wreck Orientation: The starboard side resting position limits access to critical damage zones.

- Funding Challenges: High costs and limited budgets restrict dive frequency and duration.

- Diver Hazards: Nitrogen narcosis, cold, and other risks hinder prolonged underwater work.

Consequently, while modern technology has improved remote survey capabilities, full-scale archaeological exploration remains limited. The Lusitania draws interest as a historic site and war grave, which introduces ethical considerations restricting aggressive salvage or intrusive investigation.

Key takeaways:

- The wreck’s 90m depth is technically challenging for divers and not cost-effective for deep submersibles.

- Sternward starboard orientation hides key torpedo damage details.

- Early exploration prioritized salvage with limited archaeological documentation.

- Financial and logistical constraints continue to restrict extended exploration.

- Environmental risks like nitrogen narcosis and cold water dissuade prolonged dives.

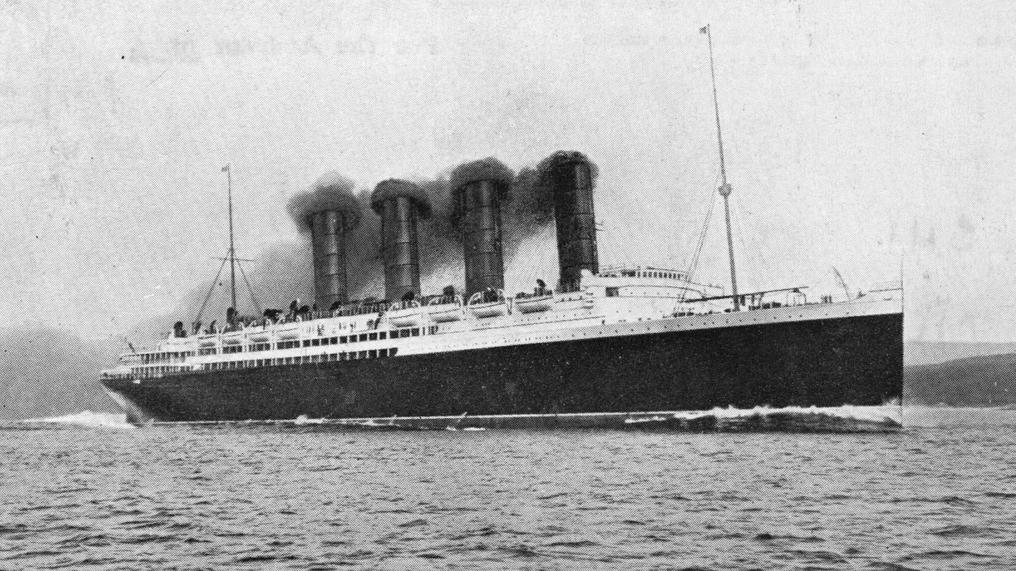

Why Hasn’t the Lusitania Wreck Been Explored More?

The Lusitania wreck remains one of the ocean’s great mysteries, not because people don’t want to explore it, but because a mix of depth, technical hurdles, funding, and downright tricky conditions stops many serious investigations.

So, why exactly is this famous wreck in the North Atlantic sticking stubbornly to its secrets? Let’s take a deep dive into the real reasons behind the sparse exploration of the Lusitania.

Early Curiosity That Was More About Gold Than History

Right after Lusitania sank in 1915, people were buzzing about her resting place—not because of the tale she told but because rumors swirled of treasure aboard. Stories of gold, bonds, jewelry, and metals like brass and copper attracted treasure hunters more than historians.

In 1935, a brave group from Glasgow, armed with an early echosounder (basically a fancy fish finder), found the wreck resting 95 meters deep. Jim Jarratt, a diver from that team, got a quick look but was hampered by dim light and clunky gear. One dive, one glimpse, and that was it—Mother Nature and World War II stepped in to put a halt on further exploration.

The Depth Dilemma: Too Shallow for Subs, Too Deep for Divers

The Lusitania sits at about 90 meters underwater, a really awkward spot. For most divers, this depth isn’t a casual swim—it demands advanced diving techniques like trimix diving, which mixes oxygen, nitrogen, and helium to prevent conditions like nitrogen narcosis.

But on the flip side, 90 meters isn’t deep enough to justify the high cost of deep-diving submarines. These submarines are designed for much greater depths, so sending one costs big bucks and feels like using a tank to squash a bug.

Adding to this, the wreck rests on her starboard side—the very side hit by the deadly torpedo during her final moments. This sideways position hides the destruction from easy access, making it tough to assess the torpedo damage or get meaningful photos.

Conditions That Would Make Even the Hardiest Diver Think Twice

Diving at this depth brings challenges beyond oxygen mixes. Early explorers, like those who completed 42 dives with compressed air, suffered from nitrogen narcosis, the terrifying “rapture of the deep” that makes you feel tipsy underwater. Picture intoxication, but without the fun party music.

Plus, the water is seriously cold—chilly enough to sap strength and sharpen risks. These hazards limit how long divers can safely stay around the wreck and what they can realistically achieve.

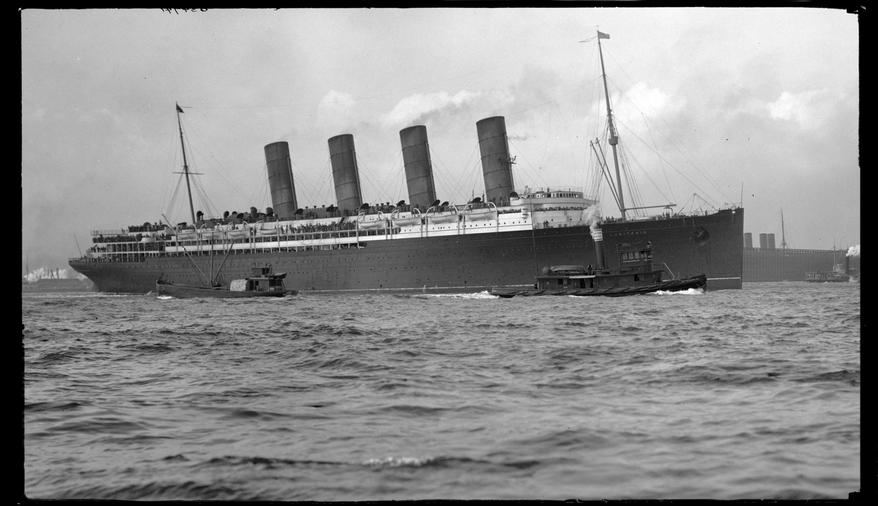

Money Talks: When Budgets Stop Exploration in Its Tracks

In 1966-67, a man named Light bought the wreck’s salvage rights for just £1000. That might sound like a bargain, but funds ran tight fast. Most of his budget went into getting a ship ready for salvage work, meaning he never managed more than initial visits to the wreck.

The high price tag for specialized equipment is a recurring barrier. Procuring advanced diving gear, remotely operated vehicles (ROVs), or tiny submarines doesn’t come cheap. Many organizations shy away when costs threaten to blow through entire project budgets.

Exploration Efforts: A Patchwork of Progress

Photo missions started early on, with British companies snapping images using primitive underwater cameras. Fast forward to 1982, Oceaneering International used ROVs to film and photograph the wreck, then sent divers to recover what they could.

Eleven years later, Bob Ballard—legendary for finding the Titanic—used the mini-submarine Delta and several ROVs for a thorough survey, bringing clarity to pieces still hidden from ordinary divers.

Since then, improvements in “trimix” scuba diving have enabled more frequent visits, but most explorers still face the same depth and financial puzzles.

Summing Up: Why the Wreck Keeps Its Secrets

- Awkward Depth: Too deep for easy dives, too shallow for big subs, making many expeditions a logistical headache.

- Wreck Orientation: Lying on its side blocks direct views of torpedo damage, complicating assessment.

- Costs: Specialized gear and vessels are expensive; funding often falls short of what’s needed for detailed exploration.

- Hazards to Divers: Risks like nitrogen narcosis and frigid waters limit dive duration and safety.

Do We Need to Explore More, or Is the Wreck Better Left in Peace?

This question often arises. On one hand, the Lusitania is a powerful historical site—with lessons about WWI, maritime warfare, and human stories frozen underwater.

On the other, beneath the waves lies an ocean graveyard deserving respect. Over-exploration can damage fragile remains or disturb what’s resting there. Many experts argue caretaking over meddling. What balance should we strike?

Lessons for Future Expeditions

Anyone dreaming of leading a Lusitania expedition faces no small task. To make it feasible, they need:

- Funding with stamina: Exploration is expensive and requires long-term support.

- Advanced technology: ROVs, mini-subs, and trimix diving gear are necessary tools.

- Safety protocols: Divers must be prepared for narcosis risks and cold conditions.

- Historical sensitivity: Recognizing the wreck as a war grave guides respectful exploration.

Future breakthroughs in underwater tech may one day make deeper, safer, and more cost-effective dives routine. Until then, the Lusitania will continue to rest quietly, inviting curiosity but demanding patience.

Final Thoughts

The Lusitania wreck’s limited exploration isn’t from lack of interest or awe. Instead, it stems from a perfect storm of technical, financial, and environmental challenges. The wreck lies in a “Goldilocks Zone” of difficulty—too challenging for divers, too shallow for deep-sea vehicles, and too costly for casual expeditions.

So next time you hear someone asking, “Why hasn’t the Lusitania been explored more?” you’ll have the full scoop. Sometimes, even history’s most famous shipwrecks keep their secrets simply because the sea isn’t ready to give them up yet.