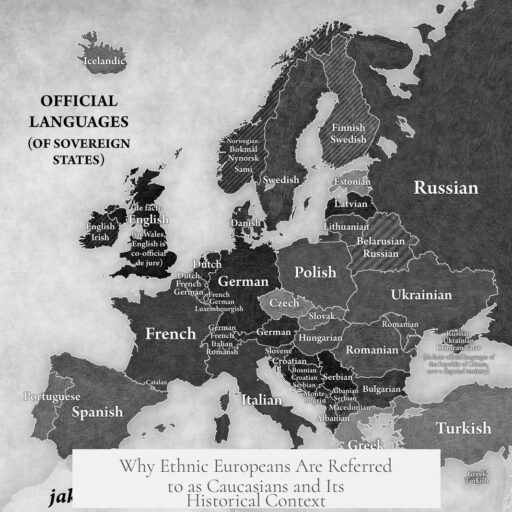

The term “Caucasian” refers to ethnic Europeans because of an 18th-century racial classification by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. He named this group after the Caucasus region, associating it with the origin of humanity and attributing superior beauty and social qualities to its people. This naming has influenced common usage ever since.

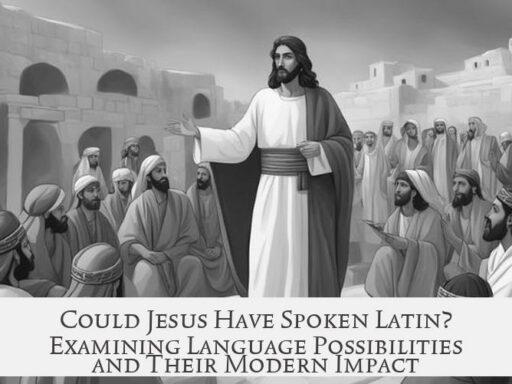

In 1795, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach published his work On the Natural Variety of Mankind, which proposed dividing humanity into five varieties: Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian, and American. His system primarily relied on craniometry—the measurement and comparison of skull shapes.

Blumenbach chose the term “Caucasian” based on his study of a skull from a Georgian woman in the Caucasus mountains. He regarded her skull as exhibiting an ideal of beauty, which influenced his belief that the people originating from this region were the most beautiful among the white racial groups. He also hypothesized that the Caucasus was the original homeland of humanity, linking this area to biblical interpretations, including the resting place of Noah’s Ark. This view gave the Caucasian group a special status as the “original” or “pure” race.

Blumenbach assigned distinctive characteristics to each of the five groups. Notably, he claimed that Caucasians alone were governed by “custom,” a notion he described as rational and adaptable social order. This suggested a form of social sophistication unique to the Caucasian group. Other groups were depicted with different traits and social principles that were often viewed as less advanced.

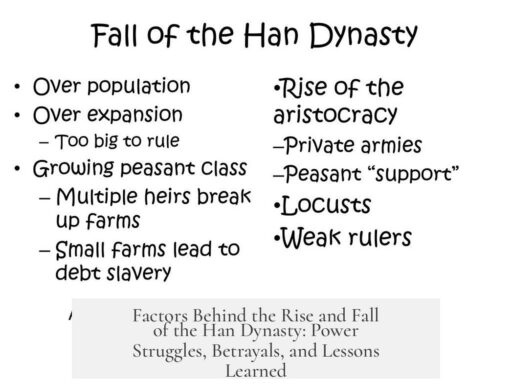

The classification system implied an implicit racial hierarchy, elevating Caucasians for their perceived beauty and supposed descent from a pure, original human stock. Blumenbach argued that Europeans, as descendants of the Caucasians, were inherently more capable of sound governance and civilization. This created a pseudo-scientific framework that masked subjective judgments under the guise of objective science.

Blumenbach’s methodology used facial symmetry and skull shape to argue for racial distinctions, presenting these criteria as scientific. However, later analysis shows these measures were highly subjective and arbitrary. The theory provided a scientific pretext that helped justify European cultural dominance and racial superiority in the centuries that followed.

Interestingly, Blumenbach personally condemned explicit racism. He believed in the relative beauty of the Caucasian type but did not claim inherent superiority or justify discrimination. Despite his more moderate views, his classification was co-opted by racists who selectively emphasized his ideas to support notions of European supremacy.

The term “Caucasian” gained strong traction due to Blumenbach’s influence in academic and social circles. He taught many students and occupied prominent positions within scientific societies. As a result, the label spread widely, entering legal, medical, and bureaucratic language globally.

Today, the term is largely abandoned by anthropologists. Modern genetics confirms there are no scientific grounds for dividing humans into racial categories. The genetic variation within so-called races exceeds that between them. Race remains a social concept rather than a biological reality.

Nevertheless, “Caucasian” persists in everyday language, especially within U.S. immigration, legal, and medical systems. Its continued use reflects inertia and the longevity of historical classifications rather than scientific accuracy.

- The term “Caucasian” originates from Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s 1795 classification based on skull studies.

- Blumenbach linked Caucasians to the Caucasus region and considered them the most beautiful and the original human group.

- The classification implied a racial hierarchy, elevating Europeans over others under a veneer of science.

- Blumenbach opposed explicit racism, but later racists misused his theory to support European superiority.

- The term remains in bureaucratic and medical use but is discredited by modern anthropology and genetics.

- Race is a social construct with no biological basis; the concept of “Caucasian” reflects outdated racial ideas.

Why Do We Call Ethnic Europeans Caucasians?

The short answer: Ethnic Europeans became known as “Caucasians” because an 18th-century scientist named Johann Friedrich Blumenbach decided to label them after the Caucasus region, based on skull shapes and a very subjective sense of beauty.

But that simple explanation masks a curious, complex tale of science, bias, and historical happenstance that still influences how we talk about race today. Ready to dive in? Let’s unpack why Europeans ended up with the name Caucasian, and what it really means.

A Skull, a Region, and a Scientist With a Mission

Back in 1795, Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a German physician and anthropologist, published a work titled On the Natural Variety of Mankind. His goal? To categorize humanity into different races using craniometry—a fancy term for measuring skulls.

Blumenbach proposed five main “varieties”: Caucasian, Mongolian, Malayan, Ethiopian, and American. So far, so biological butterfly collector. But what makes “Caucasian” special—and weird—is how and why he chose that term.

He picked the name “Caucasian” after examining the skull of a Georgian woman from the Caucasus region. To Blumenbach, this skull represented the pinnacle of human beauty and form. The Caucasus became the symbolic birthplace of mankind’s most “exemplary” group.

Think of it as naming a whole family after the most photogenic relative at the reunion. Blumenbach believed the Caucasus Mountains were where Noah’s Ark came to rest, so logically, this area was “the cradle of humanity.” From there, Europeans indirectly inherited this aura of origin and beauty.

Beauty Contest or Science? The Hidden Hierarchy

Blumenbach’s system was not just about classifying skulls. He credited Caucasians with unique social virtues too—claiming they were ruled by “custom,” a rational and adaptable social force superior to other groups.

In other words, he gave Caucasians the “smartest kid on the block” label, based on his subjective taste and some cranial measurements. This implied a subtle hierarchy where Europeans were “better” in looks, origin, and even governance.

For context: this was a world before modern genetics, so “scientific objectivity” meant what Europeans considered beautiful or civilized. It wasn’t just vanity; it seeped deep into academic and social thought.

Blumenbach’s Personal View: Not So Simple

Here’s the twist—Blumenbach himself condemned outright racism. He didn’t believe Caucasians were inherently superior. Instead, he emphasized that beauty was just one way to classify people, not a proof of worth.

Still, his work was ripe for misuse. Later thinkers cherry-picked his categories to justify European supremacy.

Blumenbach’s image of Caucasians as both the most beautiful and closest to humanity’s origin provided a handy pseudo-scientific smokescreen for racists who wanted to claim that Europeans deserved to rule.

From Academia to Everyday Life: Why “Caucasian” Stuck

Blumenbach was hugely influential during his lifetime. His teachings reached many students and seeped into powerful social circles. The word “Caucasian” entered legal documents, medical texts, and social classifications in places like the United States.

Even as anthropology discarded the concept in the 20th century, the term clung stubbornly to bureaucratic use. Immigration officials, prisons, and even hospitals would still classify people as Caucasians, sometimes synonymous with “white.”

So, while you might think the term is outdated—and you’d be right—it remains part of official language and everyday speech.

Modern Science Drops the Mask

Fast forward to today: genetics proves race as a biological reality is nonsense. Research repeatedly confirms that humans are far too mixed for neat categories to exist.

Genes don’t respect Blumenbach’s five races—they flow freely among all human groups. Despite this, race endures as a powerful social idea.

This means “Caucasian” is less a scientific term and more a historical artifact. It’s like calling VHS “modern video.” Accurate? No. Still around? Unfortunately, yes.

What Can We Learn from This?

- Labels reflect history and power. The word “Caucasian” roots back to 18th-century ideas about beauty, origin, and hierarchy.

- Science isn’t always objective. Blumenbach’s “data” mirrored European biases more than biological facts.

- Words matter. Using “Caucasian” uncritically can perpetuate outdated ideas about race.

- Critical thinking is key. Understanding terms’ origins helps us navigate modern social and racial discussions.

Real-World Tips: Talking About Race Today

Next time the term “Caucasian” pops up, consider this: it’s a word with decades of baggage. Try to clarify what it means in context. Are people referring to a legal category, a historical racial concept, or something else?

Medical professionals are shifting toward more precise terms, focusing on ethnicity or genetic ancestry rather than broad categories. For everyone else, it helps to ask: Am I using this word to describe heritage, appearance, or something else?

Using accurate and respectful language signals awareness—and maybe nudges us closer to a world where superficial skull shapes don’t decide human worth.

Wrapping It Up: Europeans Aren’t Just “Caucasians” Because of Geography or Genes

Calling ethnic Europeans “Caucasians” comes from Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s 18th-century racial thought experiment. It linked a single skull’s beauty and a legendary birthplace to an entire continent’s people. This sparked a hierarchy under a veneer of science, influencing social views for centuries.

Modern genetics reject these categories, but social habits and history keep the term alive, often without anyone knowing how it got there.

Next time you meet the word “Caucasian,” remember: it’s more story than science, more history than biology. And that makes all the difference.