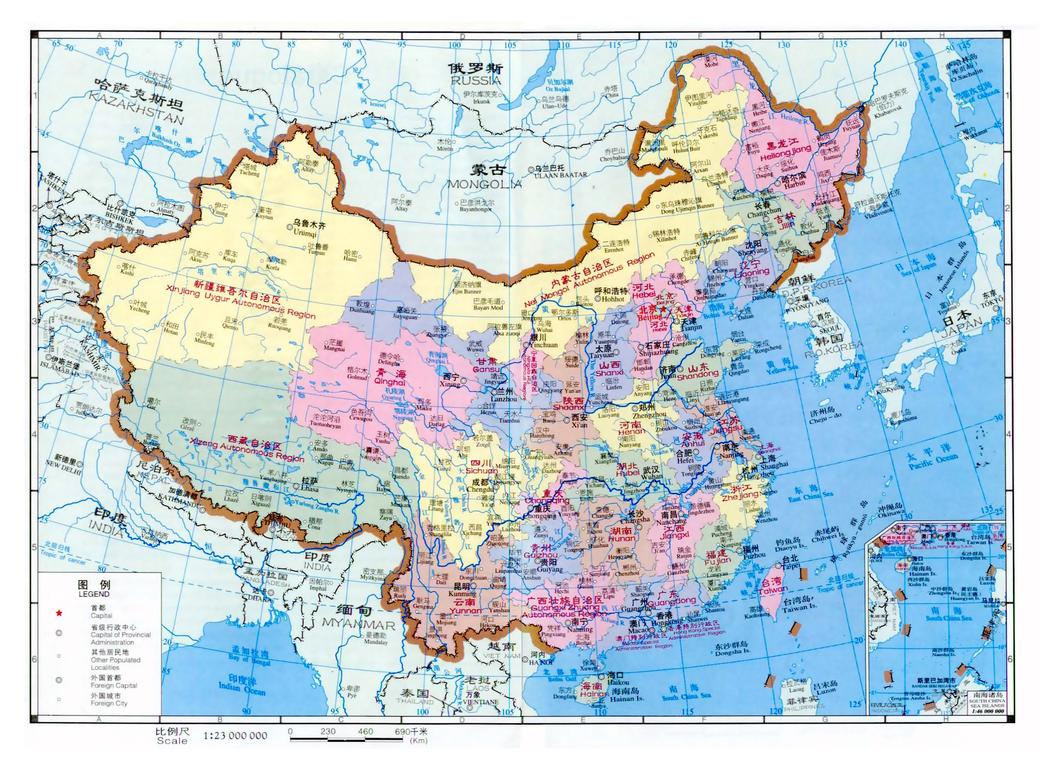

China and India have such large populations because their geography, climate, agricultural advancements, historical developments, and cultural factors created ideal conditions for sustained human habitation and growth.

Both countries occupy areas with rich natural resources and fertile lands, especially along major river systems. The Himalayas’ extensive river network supports over a billion people with ample fresh water. Similarly, the Indus and Ganges rivers nourish vast expanses of cultivable land. Historically, regions like the Indus Valley hosted one of the world’s oldest continuous civilizations, indicating long eras of stable human settlement.

These geographic features provided more than just water. They enabled transportation, soil renewal, and favorable climates for growing staple crops, making large-scale food production possible early on. Unlike Europe, which experienced restrictive climate conditions, or North America, whose population developed later, South Asia and China have had human populations for tens of thousands of years.

Agricultural technology amplified population size. In China, rice cultivation evolved through innovative methods, enhancing food availability. Rice yields more calories per acre than wheat, a staple common in Europe and the Middle East, which helped support denser populations. Rice farming is labor-intensive and calorie-rich, allowing an acre of land to sustain more people but also requiring more workers—this created a stable farming class essential for long-term growth.

Population growth in China surged during the Ming and Qing dynasties, coinciding with agricultural improvements. Advances in irrigation, crop diversity, and farming tools enabled food surpluses, supporting larger communities. This combination of favorable environment and evolving technology created a feedback loop encouraging population expansion.

India’s large population also stems from extended political and social developments. The subcontinent lacked a unified governing body for much of history, comprising many kingdoms with distinct agricultural and population policies. This political fragmentation, coupled with relatively less destructive warfare, allowed human settlements to endure and multiply. Post-independence, India’s population increased rapidly due to increased life expectancy and persistently high birth rates.

Cultural attitudes in India play a critical role. Children are seen as economic and social blessings, expected to provide care for aging parents. This tradition motivates larger families. However, government efforts to reduce birth rates have faced challenges due to illiteracy, poverty, limited access to contraception, and social conservatism. Unlike authoritarian China, India’s democratic system prohibits strict population control measures, complicating demographic management.

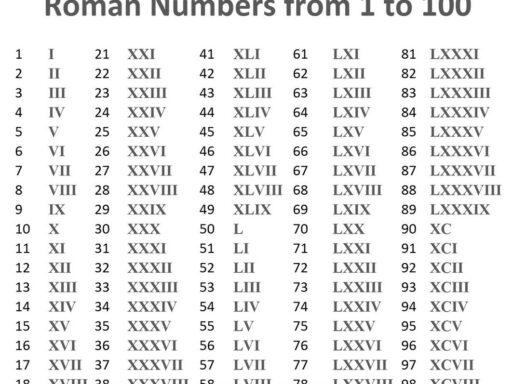

| Factors | China | India |

|---|---|---|

| Key Rivers | Yangtze, Yellow, Himalayan river system | Indus, Ganges |

| Major Crop | Rice (high calories per acre) | Rice and wheat |

| Historical Population Control | Authoritarian measures (20th century) | Democratic system, limited family planning success |

| Political Structure Historically | Unified dynasties (Ming, Qing) | Fragmented kingdoms until British Raj |

| Cultural Views on Children | Varied, but influenced by Confucian values | Children as blessing and old-age support |

Long-term continuity of civilization also matters. Both regions maintained stable farming classes that preserved and passed down agricultural knowledge for millennia. This prevented societal collapse and supported continuous population growth, unlike regions disrupted by wars or environmental catastrophes.

Some comparative historical evidence highlights differences. Around 100 AD, the Roman Empire exceeded Han China in population, but this was a brief exception. Over millennia, China and India have maintained larger populations due to sustained agricultural productivity and stable settlements.

In India today, the challenge remains to align birth rates with improvements in mortality rates. Advances in medicine have reduced deaths, but birth rates remain high due to social and systemic factors. Government corruption and bureaucracy further limit the effectiveness of population control programs.

- Geographic advantages include fertile river valleys and supportive climates.

- Agricultural staples like rice yield more calories and support denser populations.

- Long-standing civilizations enabled continuous population growth.

- In India, cultural values encourage larger families amid challenges in family planning.

- China’s historical agricultural and political centralization supported population surges.

Why do China and India have such large populations?

Simply put, China and India host large populations because their geography, history, agriculture, and cultural factors have aligned perfectly to create the world’s population giants. Now, let’s unpack that fascinating mix, piece by piece, so you’ll see why these countries are home to nearly 2.8 billion people today.

First, imagine two vast lands where humans have lived comfortably for tens of thousands of years. Both China and India unfolded as prime habitats—lush, fertile, and blessed with life-sustaining rivers. These natural conditions are no accident. Their geographic and climatic suitability laid the foundation for populations to grow, thrive, and multiply.

Think about the mighty Himalayas—an immense range that holds the key water resources for over a billion souls. The river systems fed by these mountains, including the Indus and Ganges, renew the soil regularly, enabling farms to flourish. You have rivers providing transport—and food. It’s like nature’s delivery service for growth.

Contrast this with Europe, which was frozen and inhospitable for much of prehistory, or North America, which was unpopulated until some 12,000 years ago. China and India, by contrast, were early humans’ paradise on earth.

Of course, nature alone doesn’t create superpopulation centers. Humans brought technology to the party.

Rice cultivation in China wasn’t always easy or natural. It took innovation, adaptation, and a lot of hard labor to develop effective rice farming methods. Ancient Chinese communities thrived on grains, horseflesh, and other resources long before rice fields stretched across the land.

But it was during the Ming and Qing Dynasties that agriculture got a turbo charge; technological advances led to food surpluses, which led to population booms. Simply put, better farming meant more people could be fed.

India has its own story of population expansion, rooted in fertile river valleys and centuries-old civilizations. The Indus Valley Civilization, dating back 5,000-7,000 years, demonstrates the long-term human presence and agricultural success.

Political fragmentation in India is a key twist here. Unlike a united China for much of its history, India was split into multiple kingdoms until British colonial unification. These kingdoms experimented with various farming policies, but none imposed harsh population control—meaning populations gradually increased.

Interestingly, India avoided constant large-scale wars that might have curtailed growth. The Mughal invasions caused upheaval, sure, but overall, the subcontinent experienced relative stability to nurture growing communities.

Enter modern times: in 1947, as India gained independence, it had about 350 million people with an average life expectancy of just 33 years. With high child mortality rates, families kept having many children as a buffer. But when healthcare improved, mortality dropped, while birth rates stayed high, sending populations skyward.

Why do families keep having large numbers of children even now? Culture plays a big role. Fundamentally, in Indian society children are blessings and a form of old-age security. More children often equal more hands to care for parents later on.

But there’s a catch—education and economic status dramatically affect birth rates. Wealthier, educated individuals tend to have smaller families. Unfortunately, significant portions of the population remain unaware of or unable to access family planning. Government efforts to control population haven’t hit the mark, tangled by the sheer size of bureaucracy and pervasive corruption.

Meanwhile, China took a different route, instituting strict population policies, like the one-child policy, enabled by its authoritarian government structure—a strategy India’s democracy would never approve.

Another fascinating ingredient, often overlooked but crucial, is the caloric yield from staple crops. Rice—a staple in China and much of India—produces about twice the calories per acre compared to wheat, dominant in Europe and the Middle East.

Rice farming is labor-intensive but highly efficient in calorie output. This means that every acre flooded with rice can support more people than a wheat field of the same size. It also requires many hands to tend those paddies, making rice cultivation and population growth a team sport.

This agricultural advantage partly explains why China and India support such dense populations. Their staples feed more mouths per plot of land, allowing societies to sustain larger numbers over time.

Digging even deeper, the continuity of civilizations in these regions has been impressive. Stable farming communities and hereditary farming classes maintained agricultural knowledge for millennia. This stability enhanced food security and sustained gradual population growth uninterrupted by mass societal collapse.

Interestingly, a quick check of history reminds us that this was not always a clear demographic advantage. In ancient times, like around 100 AD, the Roman Empire had a larger or similar population compared to Han China. Over time, Asia’s continued growth outpaced the West mainly due to its geographic and agricultural blessings.

So, what hinders India from slowing its population boom despite better healthcare? Birth rates haven’t dropped enough to match the decline in mortality. Social conservatism, patriarchal norms, and limited birth control education collide to make population control a tough nut to crack.

Corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency compound this, making family planning efforts spotty. The government wrestles with these challenges daily, but the scale of the problem is enormous, and solutions complex.

Now, let’s think about this: What would happen if governments manage to improve education and family planning? Would the population growth slow dramatically? The evidence suggests yes. Educated populations with better access to birth control usually see birth rates drop.

Meanwhile, China’s approach shows how a centralized, strict policy can enforce demographic control—although not without social and ethical controversies.

In closing, China and India’s massive populations are the result of lucky geography, fertile river basins, early and advanced agricultural methods, cultural values, stable farming traditions, and unique political histories. Add rice to the mix—a calorie powerhouse requiring lots of hands—and you have two enduring human epicenters.

So, next time you hear the staggering population numbers of China and India, remember it’s a story written over thousands of years with nature, human innovation, and culture all playing starring roles.

| Factor | Impact on Population |

|---|---|

| Geography & Climate | Ideal for habitation; rivers support farming and transport. |

| Agricultural Tech | Advanced rice farming boosted food supply and growth. |

| Historic Political Stability | Fewer wars and fragmented kingdoms allowed steady growth. |

| Cultural Attitudes | Children seen as blessings and security. |

| Staple Crop Calories | Rice yields double calories per acre vs wheat. |

| Continuity of Farming | Stable societies passed down farming expertise. |

| Population Control Challenges | Education and policy gaps restrict birth rate decline. |

For more details, check these resources: